THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775 -

THE BATTLE OF YORKTOWN 1781 and REASONS FOR THE BRITISH DEFEAT

xxxxxAs we have seen, following the entry of France into the war in 1778, the British switched their operations to the south, occupying Georgia, capturing Charlestown and defeating the rebels at the Battle of Camden. But resistance continued by guerrilla tactics. The British were defeated at the Battle of King's Mountain and at Cowpens in January 1781, and Cornwallis was held to a draw at Guilford Court House two months later. The crown forces then made for the Virginian coast, where Cornwallis fortified Yorktown. It proved a mistake. Wellington, together with French troops, laid siege to the port, and a large French naval force, having repulsed a British squadron at the Battle of Virginia Capes, blockaded Yorktown by sea. His forces surrounded, heavily bombarded, and fast running out of food and ammunition, Cornwallis had no alternative but to surrender his army of 8,000 men to the allied forces in October 1781. With this defeat, the war was virtually over, though it was two years before the last of the British troops left. In the meantime, at the Peace of Paris in September 1783 Britain recognised American independence.

Acknowledgements

Gates: by the American painter James Peale (1749-

G3a-

xxxxxAs we have seen, following the entry of France into the war in 1778, the British concentrated their operations in the southern states. In 1779 Georgia was occupied, Charlestown was captured with a garrison of 5,000 men, and a rebel force, led by General Gates (illustrated), was roundly defeated at the Battle of Camden in South Carolina. But these victories, impressive though they were, did not put an end to resistance. In the vast areas of wooded terrain the colonists, using guerrilla tactics, harassed their enemy at every turn, and in October 1780 won a major victory -

xxxxxAs we have seen, following the entry of France into the war in 1778, the British concentrated their operations in the southern states. In 1779 Georgia was occupied, Charlestown was captured with a garrison of 5,000 men, and a rebel force, led by General Gates (illustrated), was roundly defeated at the Battle of Camden in South Carolina. But these victories, impressive though they were, did not put an end to resistance. In the vast areas of wooded terrain the colonists, using guerrilla tactics, harassed their enemy at every turn, and in October 1780 won a major victory -

xxxxxAtxthe same time a third American army, under the command of General Nathanael Greene (1742-

xxxxxAtxthe same time a third American army, under the command of General Nathanael Greene (1742-

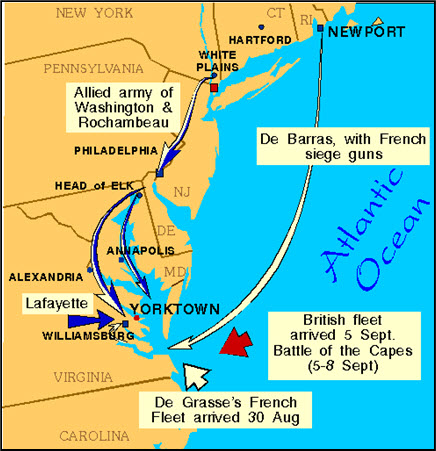

xxxxxThe British move to the coast, and the fortification of the port of Yorktown proved a mistake. At the time, in fact, General Clinton, feared that Cornwallis was laying himself open to a land and sea blockade, and so it proved to be. In September, seizing the opportunity, Washington hurried south and, supported by French troops under the Comte de Rochambeau, placed Yorktown under siege. Meanwhile a French naval force of 24 ships, led by the Comte de Grasse, had arrived in Chesapeake Bay with 3,000 troops. Axsmaller British naval squadron was despatched from New York, but was repulsed by the French at the Battle of Virginia Capes just outside the bay (illustrated) in September 1781.This serious defeat effectively cut off any hope of help by sea, whilst on land, Cornwallis found himself besieged by a force of some 14,000 Franco-

xxxxxThe British move to the coast, and the fortification of the port of Yorktown proved a mistake. At the time, in fact, General Clinton, feared that Cornwallis was laying himself open to a land and sea blockade, and so it proved to be. In September, seizing the opportunity, Washington hurried south and, supported by French troops under the Comte de Rochambeau, placed Yorktown under siege. Meanwhile a French naval force of 24 ships, led by the Comte de Grasse, had arrived in Chesapeake Bay with 3,000 troops. Axsmaller British naval squadron was despatched from New York, but was repulsed by the French at the Battle of Virginia Capes just outside the bay (illustrated) in September 1781.This serious defeat effectively cut off any hope of help by sea, whilst on land, Cornwallis found himself besieged by a force of some 14,000 Franco-

xxxxxThe massive artillery bombardment of Yorktown that then followed (3,600 heavy shot over nine days), plus the steady erosion of the port's defences, made the British position hopeless. On the 19th October 1781, totally surrounded, outgunned, and fast running out of food and ammunition, Cornwallis surrendered his garrison of 8,000 men and 240 guns to the allied forces. It was the second entire army to be lost to the rebels. The first, in 1777, marked the turn of the tide in favour of the Colonists, the second marked the end of the war. The "rebels" had triumphed. Britain began to run down its land forces, but still had to contend with French and Spanish opposition in other parts of the world, as well as the League of Armed Neutrality, a sizeable coalition of European states. In the West Indies, they won the naval Battle of the Saints in April 1782, but later that year entered into negotiations for a settlement in North America. For the British the war had become too demanding and too costly. Over the next year or so -

xxxxxThe massive artillery bombardment of Yorktown that then followed (3,600 heavy shot over nine days), plus the steady erosion of the port's defences, made the British position hopeless. On the 19th October 1781, totally surrounded, outgunned, and fast running out of food and ammunition, Cornwallis surrendered his garrison of 8,000 men and 240 guns to the allied forces. It was the second entire army to be lost to the rebels. The first, in 1777, marked the turn of the tide in favour of the Colonists, the second marked the end of the war. The "rebels" had triumphed. Britain began to run down its land forces, but still had to contend with French and Spanish opposition in other parts of the world, as well as the League of Armed Neutrality, a sizeable coalition of European states. In the West Indies, they won the naval Battle of the Saints in April 1782, but later that year entered into negotiations for a settlement in North America. For the British the war had become too demanding and too costly. Over the next year or so -

xxxxxIn brief, the major reasons for the British defeat were British miscalculation, American determination, and French intervention. The British over-

xxxxxThe major reasons for the British defeat were -

xxxxxThe major reasons for the British defeat were -

xxxxxAnd there was, too, a serious lack of co-

xxxxxThis said, the British were faced with an uphill struggle from the very beginning. Fighting a war in a hostile terrain some 3,000 miles from home, amid an armed population which became progressively more hostile and determined as the struggle continued, posed a daunting task. They were eventually worn down by a local militia and a Continental Army which, though overwhelmed at times, were inspired by the leadership of men like Washington, von Steuben and Greene. After the first flush of victory, the British redcoats fell victim to guerrilla tactics, waged by Colonists who, having a cause to fight for, knew their terrain and used their knowledge to deadly effect.

xxxxxAnd to this must be added the hit and run raids carried out by ships of the Continental Navy in British coastal waters as well as those of North America -

xxxxxAnd to this must be added the hit and run raids carried out by ships of the Continental Navy in British coastal waters as well as those of North America -

xxxxxThis cartoon, drawn in 1778 and entitled "The State of the English Nation" says it all following the French decision to enter the war. It shows an English cow being milked by a Frenchman, a Dutchman and a Spaniard, whilst an American saws off its horns. Meanwhile, a distraught Englishman is unable to arouse a slumbering British lion, and a British man-

xxxxxIncidentally, on the night of the 14th October 1781, during an attack upon the British forces at Yorktown, the Americans managed to raise the Stars and Stripes. The event was later “captured” by the French painter Eugène Lami (1800-

xxxxxIncidentally, on the night of the 14th October 1781, during an attack upon the British forces at Yorktown, the Americans managed to raise the Stars and Stripes. The event was later “captured” by the French painter Eugène Lami (1800-

xxxxx…… According to an account by an American officer who witnessed the surrender at Yorktown, “The British officers in general behaved like boys who had been whipped at school. Some bit their lips, some pouted, others cried”.