THE SETTLEMENT

THE TREATY OF LAUSANNE: TURKEY AND THE MIDDLE EAST: JULY 1923

THE SAN REMO CONFERENCE: 19th – 26th April 1920 and

THE CAIRO CONFERENCE: 12th – 30th March 1921

The Treaty of Lausanne continued, or rather replaced, the work of the Treaty of Sèvres. In fact, at conferences held in London in 1921 (21st February to 12th March), and in March 1922, the Allies did attempt to salvage the Treaty of Sèvres by precluding or watering down some of its terms, but this was strongly opposed by the Turkish National Movement. Sèvres had been concerned with the demise of the Ottoman Empire, it argued. The Versailles peace settlement had now to deal with a Turkish Republic in the making. As we have seen, after audaciously and bravely reneging on the Treaty of Sèvres, the Turks – with a deal of vital assistance from Russia – had carved out the boundaries of its nation by feat of arms. They had reconquered the new-born state of Armenia; persuaded the Italians and the French to abandon their claims on Anatolia by conceding concessions elsewhere; and, above all, had put to flight a Greek army of 200,000, bent on taking over all of western Anatolia, together with East Thrace and Istanbul. Their victory at the Battle of Sakarya had put an end to the Greek venture. Their entire army had been evacuated from the port of Izmir by mid-September 1922. And the only major member of the Allies not directly involved in this whole affair, Great Britain (save for the Chanak Crisis), was not wanting to get seriously embroiled. At this juncture both the government and the bulk of the British people had no desire to return to a state of war! Thus the Treaty of Lausanne (signed on 24th July, 1923), led to the international recognition of the sovereignty of the Republic of Turkey – proclaimed on the 29th October 1923, based at Ankara and with Mustafa Kemal as it first president. In the history of international affairs, this appeared to be the first time that the victor had conceded to the vanquished! It certainly provided a source of inspiration for nations struggling for independence at this time.

The Treaty of Lausanne continued, or rather replaced, the work of the Treaty of Sèvres. In fact, at conferences held in London in 1921 (21st February to 12th March), and in March 1922, the Allies did attempt to salvage the Treaty of Sèvres by precluding or watering down some of its terms, but this was strongly opposed by the Turkish National Movement. Sèvres had been concerned with the demise of the Ottoman Empire, it argued. The Versailles peace settlement had now to deal with a Turkish Republic in the making. As we have seen, after audaciously and bravely reneging on the Treaty of Sèvres, the Turks – with a deal of vital assistance from Russia – had carved out the boundaries of its nation by feat of arms. They had reconquered the new-born state of Armenia; persuaded the Italians and the French to abandon their claims on Anatolia by conceding concessions elsewhere; and, above all, had put to flight a Greek army of 200,000, bent on taking over all of western Anatolia, together with East Thrace and Istanbul. Their victory at the Battle of Sakarya had put an end to the Greek venture. Their entire army had been evacuated from the port of Izmir by mid-September 1922. And the only major member of the Allies not directly involved in this whole affair, Great Britain (save for the Chanak Crisis), was not wanting to get seriously embroiled. At this juncture both the government and the bulk of the British people had no desire to return to a state of war! Thus the Treaty of Lausanne (signed on 24th July, 1923), led to the international recognition of the sovereignty of the Republic of Turkey – proclaimed on the 29th October 1923, based at Ankara and with Mustafa Kemal as it first president. In the history of international affairs, this appeared to be the first time that the victor had conceded to the vanquished! It certainly provided a source of inspiration for nations struggling for independence at this time.

Incidentally, Mustafa Kemal Attaturk had this to say in 1927, “This treaty is a document declaring that all the efforts, prepared over centuries, and thought to have been accomplished through the Sèvres Treaty, aimed to crush the Turkish nation, have been in vain. It is a diplomatic victory unheard of in Ottoman history!” And in other histories too!

Acknowledgements

Cartoon: mideastcartoonhistory.com Ottoman Empire 1914: quora.com Treaty of Lausanne: en.wikipedia.org Middle East 1914 & 1923: bbc.co.uk

WW1-1914-1918-WW1-1914-1918-WW�1-1914-1918-WW1-1914-1918-WW1-1914-1918-WW1

To return to the Versailles Settlement in general, click HERE

Butxthe outstanding success achieved by the Turks in securing their independence was certainly not fully matched in the Arabian Peninsula. As we have seen, three events in particular ensured that:

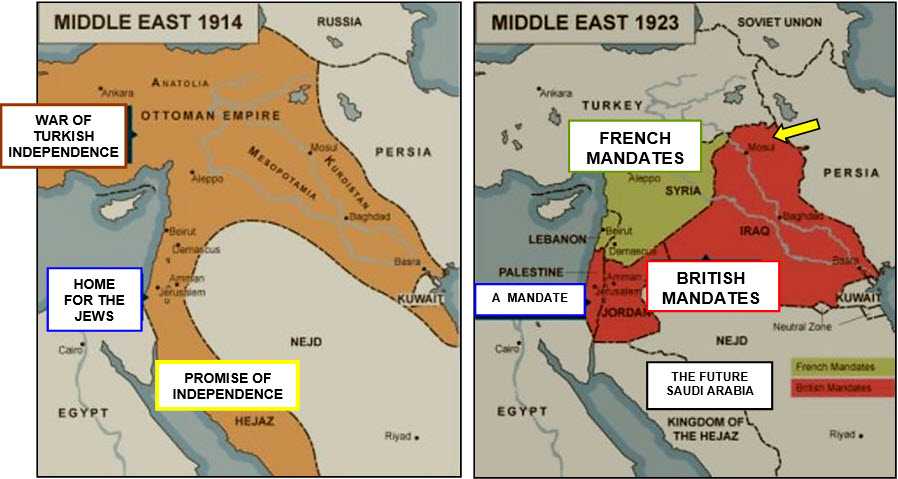

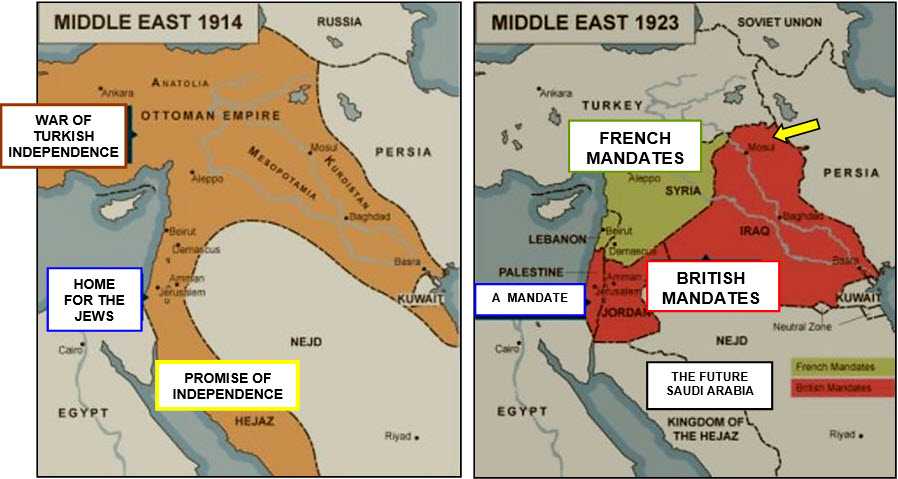

The Sykes-Picot Pact: This secret understanding between France and Britain, made in May 1916, virtually carved up the Middle East (or what was seen as its valuable regions!) between the French and the British. The French were to take over what came to be known as Syria and part of today’s Lebanon, and the British were to take over what came to be known as Iraq and the area known as Transjordan (see map below). At one time the British did consider including the Arabs themselves in this parcelling out of the Arabian Peninsula – in some measure at least – but France had to be included in the settlement, and it was known that the French were totally opposed to offering independence to the Arabs in any shape or form. Picot made it quite plain that placing Christians living in the Lebanon under a Mohammedan ruler was “quite unthinkable”. However, in March 1917, via “The Proclamation of Baghdad”, the British government did recognise that many Arabs, fighting alongside the British, had perished in the cause of Arab freedom. It was determined that “these noble Arabs shall not have suffered in vain”. At that time, Britain seemed to see itself as the liberator of those who had lived under Ottomanxoppression.

The Balfour Declaration: This British plan to establish a home for the Jews in Palestine, put forward in November 1917, met with violent opposition from within the Arab World, but was destined to be given international approval. This, together with the colonial aspirations revealed in the Sykes-Picot Pact (originally drawn up in secret), added much to Arab discontent at this time.

The San Remo Conference: Thisxmet in April 1920, and, having negotiated the terms of the Sèvres Treaty (noted earlier), turned its attention to the postwar settlement of the Middle East in general. It determined the allocation of the League of Nation mandates for the administration of the French and British territories, and confirmed the establishment of a national home for the Jews in what had been the Land of Israel. In July 1922, via the League of Nations, 51 countries recognised this historical connection, and voted in favour of the proposal. However, it contained the proviso that this course of action must in no way interfere with the rights of the existing non-Jewish communities. This, of course, proved to be a forlorn hope.

Then inxMarch 1921 the Cairo Conference was held, a series of meetings to finalize the peace settlement within the Arabian Peninsula. Chaired by Winston Churchill, then serving as the British Colonial Secretary, and attended by Lawrence and Gertrude Bell – two people with a profound knowledge of the area and its inhabitants – it was an attempt to produce a workable solution by going some way to meeting the demands of the Arab World. As far as the French were concerned, both Syria and the Lebanon were declared mandates, and Syria was divided into four sub-states to minimise Arab nationalism and racial differences. In the British territories, the part played by Sharif Hussein Ibn Ali, the leader of the Great Arab Revolt in June 1916, and the contribution made by his sons during that rebellion, were acknowledged. Hussein was recognised as King of Hedjaz; his son Faisal – the close friend and confident of T.E. Lawence – was installed as King of Iraq; and Abdullah became Emir of Transjordan. Further south another British ally, Ibn Saud, retained command of the vast region of Nejd (conquered in 1912), and it was he who established the state of Saudi Arabia, under his kingship, in 1932. (See maps below).

THE VERSAILLES TREATY: THE VERDICT OF HISTORY

By the Treaty of Lausanne, the Turks retained full sovereign rights over its territory; occupied Thrace up to the Maritsa River, and regained from Greece the islands of Gökçeada and Bozcaada. No limitations were imposed on the make-up or size of the Turkish military establishment, and no reparations were exacted. And, in an attempt to avoid long term religious problems, a compulsory exchange of population between Greece and Turkey was introduced, despite the extreme hardship that this caused. In this “unmixing” of populations (seen by some as a legalised form of mutual ethnic cleansing), about 1.1 million Greeks (mainly from Izmir), were deported from Turkey, and some 400,000 Turks were repatriated. Also established was a League of Nations Commission to supervise access to the Black Sea. Turkey did not regain complete control over the straits until 1936. In return for this generous settlement, Turkey accepted the establishment of mandates in Palestine, Syria and Cyprus, and the Italian occupation of the Dodecanese Islands in the Aegean Sea.

Incidentally, the city of Mosul (arrowed), was originally intended to be within Syria, but by an Anglo-French agreement in 1918, France gave the city over to the British mandate of Iraq and, in return, was granted a 25% share in Iraq’s oil production!

Churchill considered that, by providing these mandates, the spirit if not the actual letter of British wartime promises to the Arabs had been fulfilled. The Arabs, however, regarded these mandates as “thinly veiled forms of colonialism”. Both the French and British governments provided the financial support and, as a consequence, determined policy. Furthermore, the carve up (as in Africa) had been made with little regard, if any, to ethnic, religious, tribal and, in some instances, language considerations. And in addition to reneging on promises of self-determination, Palestine, a former possession of the Ottoman Empire, was now to have an alien race imposed upon it. The Arabs feared that this “home” was clearly destined to grow substantially in size, and bring in its wake a long and bitter conflict … as, indeed, it did!

As far as Lawrence was concerned, this settlement was something of a compromise, but, in essence, it remained a betrayal, and a source of regret for the rest of his life. But the commercial and military interests of these two colonial powers, France and Britain, were not to be thwarted. The Arabian Peninsula, apart from being part of a vital land route to the Indian sub-continent, was destined to be a most valuable and plentiful source of oil, the driving force of the future. Furthermore, as far as Britian was concerned, the task of overseeing the establishment of a home for the Jews had its compensations. The military now had a base on the eastern seabord of the Mediterrainean, providing – alongside forces on Cyprus – nearby support for the defence of the Suez Canal. The concept of Empire had survived, albeit in a modified form. The Age of Colonialism (an inevitable stage in history), still had some time to run.

The Treaty of Lausanne continued, or rather replaced, the work of the Treaty of Sèvres. In fact, at conferences held in London in 1921 (21st February to 12th March), and in March 1922, the Allies did attempt to salvage the Treaty of Sèvres by precluding or watering down some of its terms, but this was strongly opposed by the Turkish National Movement. Sèvres had been concerned with the demise of the Ottoman Empire, it argued. The Versailles peace settlement had now to deal with a Turkish Republic in the making. As we have seen, after audaciously and bravely reneging on the Treaty of Sèvres, the Turks – with a deal of vital assistance from Russia – had carved out the boundaries of its nation by feat of arms. They had reconquered the new-

The Treaty of Lausanne continued, or rather replaced, the work of the Treaty of Sèvres. In fact, at conferences held in London in 1921 (21st February to 12th March), and in March 1922, the Allies did attempt to salvage the Treaty of Sèvres by precluding or watering down some of its terms, but this was strongly opposed by the Turkish National Movement. Sèvres had been concerned with the demise of the Ottoman Empire, it argued. The Versailles peace settlement had now to deal with a Turkish Republic in the making. As we have seen, after audaciously and bravely reneging on the Treaty of Sèvres, the Turks – with a deal of vital assistance from Russia – had carved out the boundaries of its nation by feat of arms. They had reconquered the new-