THE BOSTON TEA PARTY 1773 (G3a)

xxxxxIn 1767 the British government, anxious to reduce its financial burden, imposed import duties on a number of essential items arriving in the American colonies, such as paper, glass and tea. As in the case of the Stamp Act of 1765, this caused widespread rebellion and, as we have seen, led to the “Boston Massacre” of 1770. This violent act, in which five citizens were killed by British troops, united the colonies in their opposition to the import duties, and Britain was obliged to withdraw them. It kept the tax on tea, however, and this led to the protest known as the “Boston Tea Party”. In December 1773 some sixty colonists, disguised as Mohawk Indians, boarded three ships in Boston harbour, and threw overboard a huge cargo of tea -

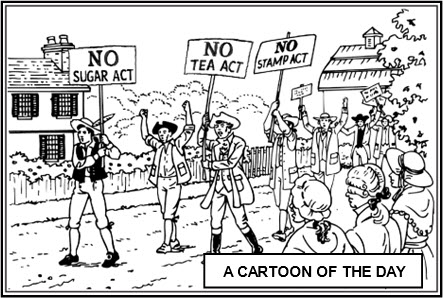

XxxxxBritain’s troubles with her American colonies began in 1765, just two years after the Treaty of Paris which ended the Seven Years’ War. The Stamp Act of that year, taxing the American colonies to help pay for their defence, caused widespread rioting. The tax, imposed by the British parliament on all publications and legal documents, was strongly opposed on the grounds that no government had the right to tax a people who were not represented within that governing body. So widespread and severe was this protest that the following year the British government felt obliged to repeal the Act.

XxxxxBritain’s troubles with her American colonies began in 1765, just two years after the Treaty of Paris which ended the Seven Years’ War. The Stamp Act of that year, taxing the American colonies to help pay for their defence, caused widespread rioting. The tax, imposed by the British parliament on all publications and legal documents, was strongly opposed on the grounds that no government had the right to tax a people who were not represented within that governing body. So widespread and severe was this protest that the following year the British government felt obliged to repeal the Act.

xxxxxHowever, two years later, determined to reduce its financial burden, parliament introduced a number of “external customs duties” on a wide range of essential imports, such as paper, paint, glass and tea. Once again violent protests broke out across the colonies and, as we have seen, these came to a head in the so-

xxxxxIt hoped in vain. In 1773, some 60 colonists in Boston, Massachusetts -

xxxxxIt hoped in vain. In 1773, some 60 colonists in Boston, Massachusetts -

xxxxxThis flagrant act of defiance, which came to be known as the “Boston Tea Party”, outraged King George III. He demanded that parliament take drastic action against Massachusetts and the “rebels”. In March the following year Lord North’s government passed the Coercive Acts, a number of punitive measures designed to bring the colonists to heel. Known in North America as the “Intolerable Acts”, they permitted the billeting of soldiers in the homes of the colonists, moved the capital from Boston to Salem, and closed the port of Boston itself -

xxxxxFor the colonists these harsh measures, following on from the Boston Massacre, proved the last straw. Amid widespread indignation and resentment, Virginia convened a protest meeting. In September 1774 some 50 representatives from all the colonies except Georgia met at Philadelphia to attend the First Continental Congress. This called for civil disobedience against British authority, drew up a Declaration of Rights and Grievances, and appealed directly to King George for fair treatment. At this stage, independence from Britain was explicitly rejected. The Congress sought only a restoration of harmony between Britain and the colonies, but all this changed when parliament rejected its petition. Then the drift to war became inevitable. Indeed, by the time the Congress held its second meeting in May 1775 the armed conflict had already begun, and there was open talk of the colonies as “free and independent states”. As we shall see, the opening shots in the American War of Independence -

xxxxxFor the colonists these harsh measures, following on from the Boston Massacre, proved the last straw. Amid widespread indignation and resentment, Virginia convened a protest meeting. In September 1774 some 50 representatives from all the colonies except Georgia met at Philadelphia to attend the First Continental Congress. This called for civil disobedience against British authority, drew up a Declaration of Rights and Grievances, and appealed directly to King George for fair treatment. At this stage, independence from Britain was explicitly rejected. The Congress sought only a restoration of harmony between Britain and the colonies, but all this changed when parliament rejected its petition. Then the drift to war became inevitable. Indeed, by the time the Congress held its second meeting in May 1775 the armed conflict had already begun, and there was open talk of the colonies as “free and independent states”. As we shall see, the opening shots in the American War of Independence -

xxxxxWhilst British public opinion was outraged by the Boston Tea Party, there were those inside and outside of parliament who took a more conciliatory attitude towards the colonists. This viewpoint was ably voiced by the politician Edmund Burke, later renowned for his writings on the French Revolution. In two speeches in the House of Commons, 1774 and 1775, he took the British government to task for its intransigence. The revolt of a whole people, he argued, clearly indicated a serious misunderstanding of the problem by those responsible for government. Imperial rights had to be tempered by the economic and political needs of the colonists themselves. Only by taking these into account would the colonies’ confidence in the mother country be restored. This advice, sound though it might be, came too late to stop the slide into conflict, though it is most unlikely that it would have been acted upon had it come earlier. The nature of imperial authority required a much longer time scale in which to change.

xxxxxWhilst British public opinion was outraged by the Boston Tea Party, there were those inside and outside of parliament who took a more conciliatory attitude towards the colonists. This viewpoint was ably voiced by the politician Edmund Burke, later renowned for his writings on the French Revolution. In two speeches in the House of Commons, 1774 and 1775, he took the British government to task for its intransigence. The revolt of a whole people, he argued, clearly indicated a serious misunderstanding of the problem by those responsible for government. Imperial rights had to be tempered by the economic and political needs of the colonists themselves. Only by taking these into account would the colonies’ confidence in the mother country be restored. This advice, sound though it might be, came too late to stop the slide into conflict, though it is most unlikely that it would have been acted upon had it come earlier. The nature of imperial authority required a much longer time scale in which to change.

xxxxxIncidentally, during the “tea party” some of the tea which was dumped in the harbour was washed up on the shore. A quantity of the leaves were picked up and preserved, and these can be seen today in Boston Museum!

xxxxxAnd powerful support for the colonial cause came in 1776 with the publication of the pamphlet. Observations on Civil Liberty, the Principles of Government, and the Justice and Policy of the War with America. The work of the Welsh preacher and political and moral philosopher Richard Price (1723-

xxxxxAnd powerful support for the colonial cause came in 1776 with the publication of the pamphlet. Observations on Civil Liberty, the Principles of Government, and the Justice and Policy of the War with America. The work of the Welsh preacher and political and moral philosopher Richard Price (1723-

xxxxxPrice was born in Tynton, Glamorgan, the son of a Congregational Minister. He attended a Dissenting (Non- instant fame. He preached to crowded congregations, and he was visited by some of the most important statesmen and academics of the day. These included the prime minister himself, William Pitt, the American founding fathers Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine, the philosophers David Hume and Adam Smith, the scientist Joseph Priestley, and the agitator for prison reform John Howard. Price also influenced the writings of the feminist Mary Wollstoncraft (illustrated), one-

instant fame. He preached to crowded congregations, and he was visited by some of the most important statesmen and academics of the day. These included the prime minister himself, William Pitt, the American founding fathers Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine, the philosophers David Hume and Adam Smith, the scientist Joseph Priestley, and the agitator for prison reform John Howard. Price also influenced the writings of the feminist Mary Wollstoncraft (illustrated), one-

xxxxxAmong other works published by Price were The Review of the Principal Questions in Morals of 1757 (containing his theory of ethics), An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the National Debt, and An Essay on the Population of England. His Essay towards Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances -

Acknowledgements

Tea Party: lithograph by the American artists Nathaniel Currier (1813-

G3a-

Including:

Richard Price