ADAM SMITH 1723 -

xxxxxThe Wealth of Nations of 1776, the major work of the Scottish economist Adam Smith, elevated economics into a separate branch of Science. In it he attacked Mercantilism -

xxxxxThe Scottish economist Adam Smith is generally regarded as the founder of modern economics. In his mammoth work An Inquiry into the nature and causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, economics came of age as a separate branch of study, divorced from political science and related subjects. His penetrating appraisal into how wealth is produced and distributed still has much relevance today -

xxxxxThe Scottish economist Adam Smith is generally regarded as the founder of modern economics. In his mammoth work An Inquiry into the nature and causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, economics came of age as a separate branch of study, divorced from political science and related subjects. His penetrating appraisal into how wealth is produced and distributed still has much relevance today -

xxxxxSmith was born in Kirkcaldy, near Edinburgh, and attended both Glasgow and Oxford Universities. Afterwards he became a lecturer on rhetoric at Edinburgh and it was here that he developed a close friendship with the Scottish philosopher David Hume, an association which had a marked effect upon his own economic and ethical thought. He was appointed professor of moral philosophy at Glasgow in 1752, a post he held for eleven years. His ethical teachings here formed the basis of his first major work of 1759, a thought- the philosophical theme of which finds an echo in The Wealth of Nations

the philosophical theme of which finds an echo in The Wealth of Nations

xxxxxIn 1763 he became tutor to Henry Scott, the young duke of Buccleuch, and accompanied him on an 18 month tour of France and Switzerland, a journey which enabled him to meet the leading members of the Physiocratic School. He was particularly impressed by the theories advanced by its leader, the French philosopher François Quesnay. On his return in 1766 he spent the next ten years in his home town or in London, writing up The Wealth of Nations. For the last twelve years of his life he served as commissioner of customs for Scotland and, for a short time, was lord rector of Glasgow University.

xxxxxThe main thrust of his The Wealth of Nations -

xxxxxThe main thrust of his The Wealth of Nations -

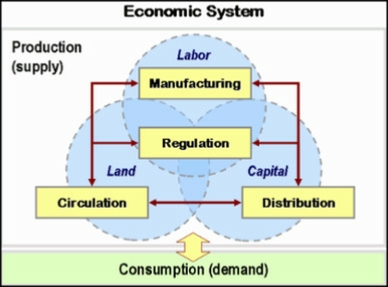

xxxxxThis theory was related to Smith's definition of national wealth, and ran counter to current thinking. Mercantilism, in vogue since the 16th century, held that the key to a nation's prosperity could be measured by the amount of bullion or treasure it held. It followed that trade needed to be regulated by government subsidies or taxes to ensure that there was a surplus of exports over imports. For Smith, however, national wealth was based on the production of consumable goods, and the labour that produced them. Given this definition, any restriction or interference in free competition could be harmful. This argument, developed in book four, demolished the bullion theory of wealth and laid down the foundations of modern capitalism.

xxxxxIn the matter of international trade, Smith argued that free trade accorded with the principle of natural liberty and produced the maximum amount of produce at the lowest possible price. Countries needed to increase their wealth by exporting those goods in which they had the economic advantage, whilst importing those goods that were produced more cheaply elsewhere. By such means everybody gained. And in the production of manufactured items, he was the first to put forward the economics of the division of labour. Efficiency was to be gained, he suggested, by dividing the manufacturing process into a series of steps, each carried out by a different work force. This not only increased production, but also reduced the level of skill required by each worker. (As we have seen, it was about this time that the English pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood began to introduce such methods in his factory at Etruria).

xxxxxIn the matter of international trade, Smith argued that free trade accorded with the principle of natural liberty and produced the maximum amount of produce at the lowest possible price. Countries needed to increase their wealth by exporting those goods in which they had the economic advantage, whilst importing those goods that were produced more cheaply elsewhere. By such means everybody gained. And in the production of manufactured items, he was the first to put forward the economics of the division of labour. Efficiency was to be gained, he suggested, by dividing the manufacturing process into a series of steps, each carried out by a different work force. This not only increased production, but also reduced the level of skill required by each worker. (As we have seen, it was about this time that the English pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood began to introduce such methods in his factory at Etruria).

xxxxxThe Wealth of Nations, apart from containing a reasoned vindication of the basic principles of the classical school -

xxxxxThe Wealth of Nations, apart from containing a reasoned vindication of the basic principles of the classical school -

xxxxxHeld in high esteem for the depth and quality of his work, Smith ended his career a highly respected and wealthy man. Apart from his close friendship with David Hume, he numbered among his many acquaintances -

Acknowledgements

Smith: bust by the Scottish sculptor Patric Parc (1811-

G3a-