THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1775 -

THE BATTLES OF SARATOGA 1777

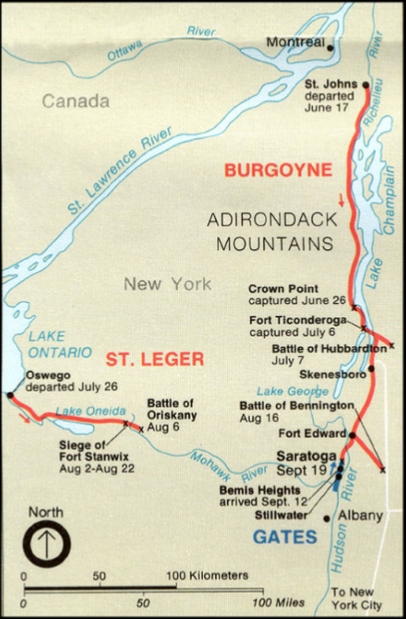

xxxxxAs we have seen, in March 1776 Washington forced the British out of Boston. In the south, however, he was driven out of New York and, after being defeated at Chatterton Hill, White Plains, was obliged to retreat southwards with General Cornwallis in hot pursuit. By December his army was seriously depleted, but by campaigning during the winter, he surprised and defeated the Hessian garrison at Trenton, and then won the Battle at Princeton. But greater success came in the north, where a loyalist attempt to drive a wedge between New England and the southern colonies ended in failure at the Battles of Saratoga in 1777. A 9,000 strong loyalist force under General John Burgoyne moved south from Canada, and by July had reached and captured Fort Tinconderoga. From then onwards, however, it came under constant guerrilla attack and, on coming close to Albany, was confronted by a large patriot army. Badly defeated at the Battles of Freeman's Farm and Bemis Heights, and waiting in vain for support from New York, Burgoyne was forced to surrender at Saratoga in October. Meanwhile General Howe, unaware that he should have linked up with Burgoyne, took his army south, defeated Washington at Brandywine Creek, and seized Philadelphia. As we shall see, the success at Saratoga was not only a great boost to the rebels, but in 1778 it persuaded the French to take up arms in their support -

xxxxxAs we have seen, in March of 1776 Washington forced the British out of Boston. Having established gun emplacements on nearby Dorchester Heights, he virtually commanded the city. On the 17th the British General Howe decided to evacuate his forces to Halifax in Nova Scotia. Further south, however, Washington faced a series of defeats. In August, the British, now adequately reinforced to crush the rebellion, defeated him at the Battle of Long Island, and then drove him off Manhattan. A further defeat followed at Chatterton Hill, near White Plains, and he was forced to retreat southwards across New Jersey, closely pursued by a British force under General Cornwallis. Having reached the Delaware, however, he gained some comfort by defeating the Hessian garrison at Trenton in late December, and then winning the Battle of Princeton early in the New Year. By now, his army was seriously depleted and not in good shape, but the victories at Trenton and Princeton served as a psychological turning point.

xxxxxAndxthe much needed military turning point was to come with the Battles of Saratoga later in 1777. The British, having captured New York, were now anxious to split the colonies by driving a wedge between New England and the colonies to the south. To achieve this, it was planned that an invasion force from Canada, led by General John Burgoyne (1722-

xxxxxAndxthe much needed military turning point was to come with the Battles of Saratoga later in 1777. The British, having captured New York, were now anxious to split the colonies by driving a wedge between New England and the colonies to the south. To achieve this, it was planned that an invasion force from Canada, led by General John Burgoyne (1722-

xxxxxLeading a force of some 9000 troops, made up of British, Germans and Indians, Burgoyne moved southwards down the course of Lake Champlain and the Hudson River, and by early July had captured Fort Ticonderoga. Up to this point he had encountered little resistance, and life for his senior officers and their wives/mistresses (or both!) was one round of leisurely pleasure. From here, however, instead of using Lake George, he chose the arduous land route through the dense forestland of upper New York State. As a result, he found the only road constantly blocked by felled trees, and suffered heavy loses from the guerrilla-

xxxxxInxmid-

xxxxxInxmid-

xxxxxAs one can imagine, the defeat of a British army was a major boost to the revolutionary cause. Above all, however, the rebel victories at the Battles of Saratoga played a major part in persuading the French not only to recognize American independence, but to give open military assistance in its support. As we shall see, the French entry into the war in 1778 was the first step towards turning a civil war into an international conflict. This was indeed a decisive turning point.

xxxxxIn apportioning blame for the British debacle, the tactics and attitude adopted by Burgoyne are clearly open to question, but the plan itself, though strategically sound, was flawed from the start. No one, it seems, had given General Howe any clear idea of the part he had to play in it! As a consequence, Howe did not march north to join up with Burgoyne, but, leaving a garrison in New York, he transported his army by sea to Chesapeake Bay. Once landed there, he defeated Washington's forces at Brandywine Creek (illustrated) and, towards the end of September, occupied the American capital of Philadelphia -

xxxxxIt was in this year, in June, that the Continental Congress approved the first, official national flag, known as the Stars and Stripes or "Old Glory". As shown, it had 13 stripes and 13 stars to represent the states, but the layout varied. By 1795 two more states had been added to the Union and the flag, now given the name the "star spangled banner", had 15 stars and stripes. With more states joining, however, the layout became progressively difficult, and in 1818, by an act of Congress, the stripes were reduced to 13 to represent the original states. Legend has it that the flag actually dates from May 1776, when George Washington himself, together with two Congress members, hired Betsy Ross (1752-

xxxxxIt was in this year, in June, that the Continental Congress approved the first, official national flag, known as the Stars and Stripes or "Old Glory". As shown, it had 13 stripes and 13 stars to represent the states, but the layout varied. By 1795 two more states had been added to the Union and the flag, now given the name the "star spangled banner", had 15 stars and stripes. With more states joining, however, the layout became progressively difficult, and in 1818, by an act of Congress, the stripes were reduced to 13 to represent the original states. Legend has it that the flag actually dates from May 1776, when George Washington himself, together with two Congress members, hired Betsy Ross (1752-

Acknowledgements

Burgoyne: preparatory painting attributed to the Scottish artist John Graham (1754-

G3a-

Including:

The Stars and Stripes

or "Old Glory"