xxxxxIt was Martin Luther in Germany who became the  revolutionary leader, though, in fact, his attack on indulgences in 1517 was meant as a criticism not a clarion call to revolt! Wellxbefore his death some 300 North German princes had adopted the new form of faith, and when the second Diet of Speyer attempted to put the clock back in 1529, the loud protest then made gave the movement its name: Protestantism. It was these Protestants who the following year submitted the Augsburg Confession to the Emperor Charles V and, defining their beliefs, put an end to the ancient conception of a single Christian community under a single Christian authority. Luther was excommunicated and made an outcast -

revolutionary leader, though, in fact, his attack on indulgences in 1517 was meant as a criticism not a clarion call to revolt! Wellxbefore his death some 300 North German princes had adopted the new form of faith, and when the second Diet of Speyer attempted to put the clock back in 1529, the loud protest then made gave the movement its name: Protestantism. It was these Protestants who the following year submitted the Augsburg Confession to the Emperor Charles V and, defining their beliefs, put an end to the ancient conception of a single Christian community under a single Christian authority. Luther was excommunicated and made an outcast -

xxxxxBut the Emperor Charles V had other ideas, though for some time these had to be put on hold. Over the next ten years and more he had to lead a campaign against the Barbary pirates who, aided and abetted by the Ottoman Turks, were causing havoc along the North African coast. Moreover, the French had returned to the attack in Italy and there were troubles in the Netherlands. In 1544, however, he made a peace settlement with the French and the following year concluded an armistice with the Ottoman Empire. He could now turn his attention to the German Protestants, and he chose war as the first means of persuasion. He opened the campaign in 1546 and won the Battle of Mühlberg against the Protestant estates in 1547. On the strength of this victory he felt able to impose his own religious settlement, but he underestimated the strength of the Protestant cause. As we shall see, in 1555 (M1) he was obliged to reach a compromise at the Peace of Augsburg.

xxxxxIncidentally, in 1548 the famous Venetian artist Titian painted a portrait of Charles V on horseback to commemorate the Emperor’s victory at the Battle of Mühlberg. In this splendid painting Charles, dressed in armour, is wearing the rose sash across his chest, the symbol of the Catholic party and of the Holy Roman Empire.

xxxxxIn the Scandinavian countries there was virtually no opposition to what they called (and still call) Lutheranism. In Denmark the authority of Roman Catholic bishops was promptly abolished and this carried weight in the subject lands of Norway and Iceland. In Sweden adoption was effected as early as 1529, passed by the Diet and supported by King Gustav Vasa.

xxxxxIn Switzerland, as we have seen,  the reform

the reform  movement got under way in Zurich, led by the energetic Ulrich Zwingli (illustrated right). Under his leadership, virtually all the elements of the Roman Catholic Church were abolished, including the Mass. Berne and Basel followed suite, but the five forest cantons remained loyal to the Pope and in the ensuing civil war Zwingli was killed. Thus Switzerland remained divided, as it is today, with the Protestants situated mostly in the lowland and larger cities. As we shall see, a generation later (1536) came the French theologian John Calvin (illustrated left). His theocracy in Geneva (1541-

movement got under way in Zurich, led by the energetic Ulrich Zwingli (illustrated right). Under his leadership, virtually all the elements of the Roman Catholic Church were abolished, including the Mass. Berne and Basel followed suite, but the five forest cantons remained loyal to the Pope and in the ensuing civil war Zwingli was killed. Thus Switzerland remained divided, as it is today, with the Protestants situated mostly in the lowland and larger cities. As we shall see, a generation later (1536) came the French theologian John Calvin (illustrated left). His theocracy in Geneva (1541-

xxxxxThe reformation in France was initiated by a group of humanists under the leadership of Lefèvre d’Étaples. They produced a French translation of the bible, but once their true motives were realised, they were persecuted. Many fled to Switzerland, but by June 1545 some 3,000 had been put to death. Nevertheless, the protestant movement continued to grow, and, as we shall see (1562 L1), was to lead to over 40 years of civil war. A strong line against the Protestants was also taken by Charles V in the Netherlands. Luther’s books were publicly burnt and the Inquisition was established in 1522, but despite these measures the new faith had gained a firm hold on the northern  provinces by the middle of the century.

provinces by the middle of the century.

xxxxxIn Scotland there was far less opposition to the spread of Protestantism. The Roman Catholic clergy were not held in high esteem, and the presence of Lollards, the followers of John Wycliffe, provided a ground-

xxxxxMeanwhile in England, as we shall see (1534),  the Reformation was motivated by political need, not religious pressure. Henry VIII wanted a divorce from his wife, Catherine of Aragon, and as the pope would not grant it, he organised the divorce himself, put into practice by his ministers Thomas Cromwell (illustrated) and Thomas Cranmer. This clearly meant a break from Rome, finalised in 1534 when he became head of the English Church. In fact, Henry himself had no time for Luther and no sympathy with the protestant cause. Indeed, his Six Articles of 1539 enforced much of Roman Catholic doctrine. It was to be left to Edward VI and Elizabeth I (with the bloody period of the Roman Catholic Mary I in between) to establish an independent Anglican church. Nor was Protestantism confined to Western Europe. Its ideas also permeated through to Poland, Bohemia, Hungary, Moravia and other countries in the east.

the Reformation was motivated by political need, not religious pressure. Henry VIII wanted a divorce from his wife, Catherine of Aragon, and as the pope would not grant it, he organised the divorce himself, put into practice by his ministers Thomas Cromwell (illustrated) and Thomas Cranmer. This clearly meant a break from Rome, finalised in 1534 when he became head of the English Church. In fact, Henry himself had no time for Luther and no sympathy with the protestant cause. Indeed, his Six Articles of 1539 enforced much of Roman Catholic doctrine. It was to be left to Edward VI and Elizabeth I (with the bloody period of the Roman Catholic Mary I in between) to establish an independent Anglican church. Nor was Protestantism confined to Western Europe. Its ideas also permeated through to Poland, Bohemia, Hungary, Moravia and other countries in the east.

xxxxxThe results of the Reformation were wide and far reaching. This fracture in the Western Church not only brought into being a new religious denomination, it also brought the realisation that the Old Order -

THE REFORMATION IN EUROPE 1517 (H8)

xxxxxThe Reformation was nothing short of a revolution as far as Christendom was concerned, resulting as it did in the establishment of another Church in Western Europe known regionally as Protestant, Reformed or Lutheran. Following on from the Renaissance (which aided the movement in so many ways), its implications spread far beyond religious matters, having an impact on both politics and economics in the structure of Europe -

short of a revolution as far as Christendom was concerned, resulting as it did in the establishment of another Church in Western Europe known regionally as Protestant, Reformed or Lutheran. Following on from the Renaissance (which aided the movement in so many ways), its implications spread far beyond religious matters, having an impact on both politics and economics in the structure of Europe -

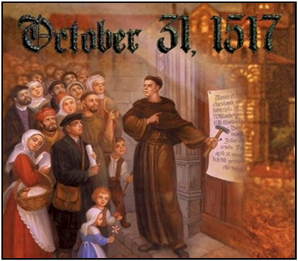

xxxxxMartin Luther gave vent to many people’s feelings when he nailed his protest against indulgences to a church door at Wittenberg in 1517. But such misgivings about the Roman Catholic Church had been about for hundreds of years and were certainly not confined to one particular grievance. As early as 962 when the German king Otto 1 revived the Holy Roman Empire, the scene was set for the conflict between the supremacy of the pope, God’s representative on earth, and the secular leaders who strove to carve out and keep power within their own land and -

xxxxxAs far back as the thirteenth century the papacy was being attacked for the immorality and greed of its clergy, and the many privileges they enjoyed. To this period also belongs the so-

xxxxxNor were reformers like John Wycliffe in England, Jan Huss in Bohemia, and Savonarola in Florence just voices crying in the wilderness. There were many who supported their attack upon the sale of indulgences, the excessive veneration of the saints and images, the immorality and high living of many of the clergy, the injustice of ecclesiastical courts, and the constant interference of the pope in the affairs of independent states. And alongside the coming of the Renaissance, with its revival of classical learning and its questioning of dogmatic views by humanists like Erasmus and Thomas More, had come the invention of printing, a means by which new ideas and constructive criticism could be rapidly spread. It could at last be argued that the Scriptures, now available in the language of the people, were the basis of one’s faith, not blind allegiance to a corrupt and outmoded Church based in Rome. The call was for a return to the simple faith of the Early Church whereby only the scriptures had authority, and justification was by faith alone.

reformers like John Wycliffe in England, Jan Huss in Bohemia, and Savonarola in Florence just voices crying in the wilderness. There were many who supported their attack upon the sale of indulgences, the excessive veneration of the saints and images, the immorality and high living of many of the clergy, the injustice of ecclesiastical courts, and the constant interference of the pope in the affairs of independent states. And alongside the coming of the Renaissance, with its revival of classical learning and its questioning of dogmatic views by humanists like Erasmus and Thomas More, had come the invention of printing, a means by which new ideas and constructive criticism could be rapidly spread. It could at last be argued that the Scriptures, now available in the language of the people, were the basis of one’s faith, not blind allegiance to a corrupt and outmoded Church based in Rome. The call was for a return to the simple faith of the Early Church whereby only the scriptures had authority, and justification was by faith alone.

xxxxxThe Reformation (1517) was a religious revolution resulting in the establishment of another Church, known regionally as Protestant, Reformed or Lutheran. Serious misgivings about the Roman Catholic Church had been about for hundreds of years, stemming from the bitter Investiture Controversy. Then followed attacks on the immorality, greed and privileges of the clergy. Nor was the authority of the Church helped by the Babylonian Captivity (1309-

Including:

Germany,

Scandinavia,

Switzerland,

France,

Netherlands,

Scotland and

England

Results and

The Counter

Reformation

xxxxxIn Germany, Martin Luther emerged as the revolutionary leader, though, in fact, his attack on indulgences in 1517 had merely been meant as protest against the existing order. Long before his death some 300 North German princes had adopted the new form of faith and, by their protests at the Diet of Speyer in 1529, had given the movement its name: Protestantism. The Augsburg Confession of the following year defined protestant aims and put an end to the concept of a single Church and Christian authority. But the Emperor Charles V was yet to make his move. Having concluded peace with the French and Ottoman Turks, in 1546 he attacked the Protestants and defeated them at the Battle of Mühlberg. He now felt free to impose his own religious settlement but in fact, as we shall see, he was obliged to reach a compromise at the Peace of Augsburg in 1555 (M1).

xxxxxThe Counter-

xxxxxThe Counter-

xxxxxThe Counter-

xxxxxIn facing up  to the Protestants themselves, the Roman Catholic Church had two major “instruments”. About 1542 an Index of Forbidden Books was issued in an attempt to combat the vast amount of Protestant literature spreading throughout Europe. Catholics were forbidden to read such heretical works. In addition, there was, of course, the Inquisition. This, as we have seen, was introduced by Pope Gregory IX as early as 1231 (H3) to combat the Albigensians, and was followed by the Spanish Inquisition in 1478. It now re-

to the Protestants themselves, the Roman Catholic Church had two major “instruments”. About 1542 an Index of Forbidden Books was issued in an attempt to combat the vast amount of Protestant literature spreading throughout Europe. Catholics were forbidden to read such heretical works. In addition, there was, of course, the Inquisition. This, as we have seen, was introduced by Pope Gregory IX as early as 1231 (H3) to combat the Albigensians, and was followed by the Spanish Inquisition in 1478. It now re-

xxxxxAs we shall see, the Peace of Augsburg of 1555 (M1) attempted to make a religious settlement in Germany, but this was followed in the long term by the Thirty Years’ War -

Acknowledgements

1517: illustration from Celebrating the Protestant Reformation by the Scottish philosopher John Armstrong. Map (Europe): licensed under Creative Commons – rkgregory.cmswiki.wikisaces.net. Luther: by Lucas Cranach the Elder (c1472-

H8-