THE END OF THE ITALIAN WARS

THE BATTLE OF PAVIA 1525 (H8)

xxxxxAs we have seen, 1494 (H7) saw the beginning of the Italian Wars between France on the one hand and the Habsburg rulers of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire on the other. Later, an alliance of both sides, known as the League of Cambrai, attacked and defeated Venice but collapsed in 1510. The French then took Ravenna, but were faced with a formidable enemy with the election of Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor. He moved more forces into Italy, and in 1525 met up with the French at Pavia some 20 miles south of Milan. At first the Habsburg troops were encircled, but then a large Spanish army, using muskets for the first time, attacked the French and virtually wiped them out. The French king, Francis I, was captured and, by the Treaty of Cambrai in 1529, was obliged to renounce his claims to Italy. Six years later Charles V was crowned king of Italy. The Habsburgs had triumphed.

Including:

Treaty of Cambrai,

The Sack of Rome,

Emperor Charles V,

and Francis I of France

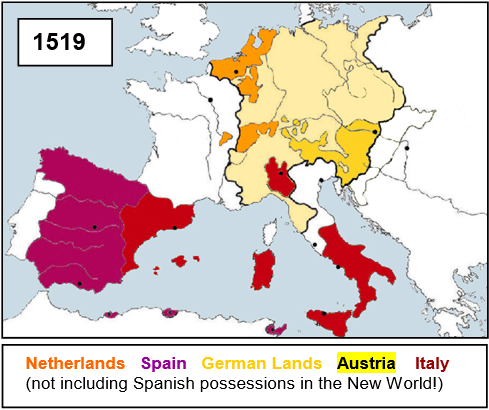

xxxxxAs we have seen, the year 1494 (H7) saw the beginning of a series of wars between France and the Habsburg rulers of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire over who was to control Italy. These “Italian Wars” opened with the French expelling the Medici from Florence, occupying Rome, and then seizing Naples and Milan. Then the Spanish moved in and, having captured Naples, took over the whole of southern Italy. Later Venice came under attack from the League of Cambrai, an alliance of both sides. Venetian forces were defeated at Agnadello in May 1509 and only regained their lost empire when the League collapsed in 1510. Two years later the French captured the city of Ravenna and secured a truce by the Peace of Noyen in 1516, but with the election of Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor in 1519 the French faced a formidable enemy. Determined to consolidate his hold on Italy, Charles moved more forces into the peninsula and, after some minor successes, won a resounding victory over the French at the Battle of Pavia in February 1525 (arrowed on map).

xxxxxAs we have seen, the year 1494 (H7) saw the beginning of a series of wars between France and the Habsburg rulers of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire over who was to control Italy. These “Italian Wars” opened with the French expelling the Medici from Florence, occupying Rome, and then seizing Naples and Milan. Then the Spanish moved in and, having captured Naples, took over the whole of southern Italy. Later Venice came under attack from the League of Cambrai, an alliance of both sides. Venetian forces were defeated at Agnadello in May 1509 and only regained their lost empire when the League collapsed in 1510. Two years later the French captured the city of Ravenna and secured a truce by the Peace of Noyen in 1516, but with the election of Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor in 1519 the French faced a formidable enemy. Determined to consolidate his hold on Italy, Charles moved more forces into the peninsula and, after some minor successes, won a resounding victory over the French at the Battle of Pavia in February 1525 (arrowed on map).

xxxxxPavia, a city about 20 miles south of Milan, was being besieged by the French when the Habsburg army arrived to relieve the garrison. Numbering some 23,000 men, they were quickly encircled by the French, but a large force of Spanish, using muskets for the first time, then opened fire on the French infantry and cavalry and turned the tide of the battle. Subsequent attacks by Swiss and German mercenaries were repulsed and the Spaniards, with the support of some 5,000 men from the Pavia garrison, fell upon the French army, originally 28,000 strong, and virtually destroyed it. Their commander, King Francis I himself, was captured and taken to Madrid.

xxxxxThe Battle of Pavia proved the  decisive engagement of the Italian Wars. By it, Spanish control in Italy was assured. Francis I was eventually released, but by the Treaty of Cambrai, agreed in 1529, he was obliged to renounce his claims in Italy and to give up his rights to Artois and Flanders. In the following year, the pope crowned Charles V Emperor and King of Italy and six years later, after his forces had captured Tunis and freed 20,000 Christian slaves, the emperor made a triumphant journey through the peninsula to confirm his authority. Despite the terms of the Treaty of Cambrai, the French did make three more excursions into Italy, but they all proved unsuccessful and in 1559, by the Peace of Cateau-

decisive engagement of the Italian Wars. By it, Spanish control in Italy was assured. Francis I was eventually released, but by the Treaty of Cambrai, agreed in 1529, he was obliged to renounce his claims in Italy and to give up his rights to Artois and Flanders. In the following year, the pope crowned Charles V Emperor and King of Italy and six years later, after his forces had captured Tunis and freed 20,000 Christian slaves, the emperor made a triumphant journey through the peninsula to confirm his authority. Despite the terms of the Treaty of Cambrai, the French did make three more excursions into Italy, but they all proved unsuccessful and in 1559, by the Peace of Cateau-

xxxxxIncidentally, The Treaty of Cambrai is often referred to as “Ladies’ Peace” because it was, in fact, concluded by two women: Louise of Savoy, on behalf of her son, Francis I, and Margaret of Austria, on behalf of Charles V, her nephew.

xxxxxThe Habsburg victory was followed by the Sack of Rome. After the Battle of Pavia, the Duke of Bourbon was made Duke of Milan in recognition of his services to Charles V. In 1527 he allowed his troops to raid the city. Some 4,000 inhabitants were killed, the pope, Clement VII, was imprisoned in Castel Sant Angelo, and valuable art treasures were looted. According to one onlooker, “Hell itself was a more beautiful sight to behold”. It was ten months before law and order were restored, and so extensive was the damage to property -

xxxxxHis victory at the Battle of Pavia was a triumph for Charles V (1500-

xxxxxThe victory  at Pavia

at Pavia was a triumph for Charles V (1500-

was a triumph for Charles V (1500-

xxxxxThese vast, world-

xxxxxThere was, too, of course, the  running battle with the French monarch, Francis I, in the struggle over Italy, a contest not finally and fully resolved until 1559, the year after his death. This weeping sore, together with his constant efforts to bring religious and political peace to his empire -

running battle with the French monarch, Francis I, in the struggle over Italy, a contest not finally and fully resolved until 1559, the year after his death. This weeping sore, together with his constant efforts to bring religious and political peace to his empire -

xxxxxFirmly established in the Balkans, the Turks, led by their great leader Suleyman, routed the Hungarians at the Battle of Mohacs in 1526 (arrowed on map), killing the Hungarian king, Louis II. Three years later he laid siege to Vienna (arrowed on map), where the city was defended by the emperor’s brother, Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, there to claim the vacant Hungarian throne. Fortunately for Europe, the stout resistance given by the garrison, combined with bad weather, the outbreak of disease and the threat of uprisings in Persia, caused the Sultan to lift the siege.

xxxxxAs we shall see, Charles, eventually worn out by the cares of his great office, abdicated in 1556 (M1) and gave away his vast territories to his son Philip and his brother Ferdinand. He then retired to a monastery for some peace and quiet!

xxxxxFrancis I of the House of Valois (1494-

xxxxxThe other major protagonist in the Italian Wars was the French king, Francis I (1494-

Italian Wars was the French king, Francis I (1494-

xxxxxThis victory, in which he led the charge, procured for him the Duchy of Milan, but his good fortune was not to last amid the Italy of his day, a hotbed of intrigue between the pope, the city states, and any would-

xxxxxAt home, Francis I became an ardent persecutor of the Huguenots (French Protestants) from 1534 onwards, and his reforms in government, principally to raise funds, created tension between the traditional nobility and a new ruling class of administrators. As an “enlightened” autocrat, he was anxious to give status to his Court, and determined to retain complete control of his domain. At the same time, he employed Italian artists, including Leonardo da Vinci, to embellish his chateaux and palaces. He built the castles at Chambord and Fontainbleau, and was responsible for the creation of a royal library, the beginnings of the Collège de France. As we have seen, one of the most lavish events of his reign was his meeting with the English King Henry VIII, held on “The Field of the Cloth of Gold” near Calais in 1520 (here illustrated).

complete control of his domain. At the same time, he employed Italian artists, including Leonardo da Vinci, to embellish his chateaux and palaces. He built the castles at Chambord and Fontainbleau, and was responsible for the creation of a royal library, the beginnings of the Collège de France. As we have seen, one of the most lavish events of his reign was his meeting with the English King Henry VIII, held on “The Field of the Cloth of Gold” near Calais in 1520 (here illustrated).

Acknowledgements

Map (Italy): from www.uc321.net. detail unavailable. Pavia: front cover of The Battle of Pavia, edited by Professor Timothy Wilson, detail of a painting produced c1526, artist unknown -

H8-