THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE - MURAD IV

1623 - 1640 (J1, C1)

Acknowledgements

Murad IV: detail of Ottoman miniature portrait, 1623-1640 – Topkapi Palace, Istanbul. Map (Ottoman Empire): licensed under Creative Commons – en wikipedia.org. Map (Barbary Coast): licensed under Creative Commons – https://apus2scott.wikispaces.com. Barbary Pirate: licensed under Creative Commons – en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Chaloner+Ogle.

Including:

The Barbary Pirates

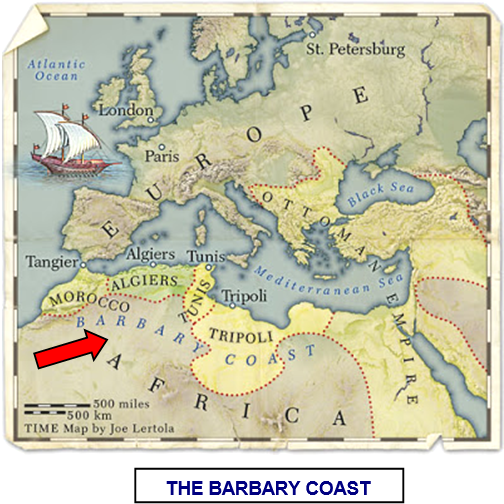

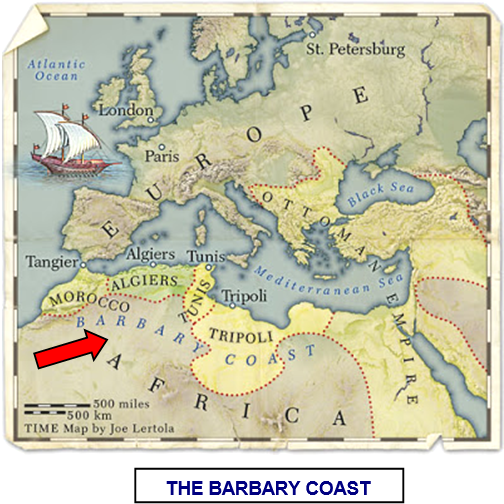

xxxxxIt was during the reign of Murad IV (1623-1640) that the Barbary Pirates began to expand their activities, replacing their cumbersome slave galleys with fast moving sailing boats. These pirates, as we have seen (1535 H8), established their bases along the North African coast from Libya to Morocco as early as Roman times, and became particularly active with the expulsion of the Moors from Spain in 1492. The Spanish made several attempts to destroy or capture the ports from which they operated, but without success. In 1535 the Holy Roman Emperor himself, Charles V, launched a campaign against their land bases and did manage to capture Tunis for a short while, but three years later, led by their able chief Barbarossa (Khair-ed-Din), the pirates managed to defeat the emperor’s fleet at the Battle of Preveza and extend their control into the eastern Mediterranean.

xxxxxIt was during the reign of Murad IV (1623-1640) that the Barbary Pirates began to expand their activities, replacing their cumbersome slave galleys with fast moving sailing boats. These pirates, as we have seen (1535 H8), established their bases along the North African coast from Libya to Morocco as early as Roman times, and became particularly active with the expulsion of the Moors from Spain in 1492. The Spanish made several attempts to destroy or capture the ports from which they operated, but without success. In 1535 the Holy Roman Emperor himself, Charles V, launched a campaign against their land bases and did manage to capture Tunis for a short while, but three years later, led by their able chief Barbarossa (Khair-ed-Din), the pirates managed to defeat the emperor’s fleet at the Battle of Preveza and extend their control into the eastern Mediterranean.

xxxxxThe defeat of the Ottomans at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 put a brake on their activities for a time, but by 1580s they were well back in business, preying upon the merchant ships that criss-crossed the Mediterranean, and carrying out coastal attacks - especially in Spain, Sicily and the Kingdom of Naples - to capture slaves for work or ransom.

xxxxxIn the early part of the 17th century, the pirates of Algeria and Tunisia joined forces, and the Moroccans began to take a more active part, based mainly on the port of Sale. These developments, together with the change from oar to sail, made piracy an even bigger enterprise along the Barbary coast. Pirate ships now ventured into the Atlantic, going as far as the Canaries in the south and Iceland in the north. The British Isles could now be targeted. In 1663, for example, a raid was made on the port of Baltimore on the south coast of Ireland and, at about the same time, St. Ives and Salcombe in south-west England were attacked and violently plundered. By such expeditions, hundreds of men, women and children were captured and taken back to the slave markets in North Africa. It is estimated that by 1650 some 30,000 captives were held as slaves in Algiers alone. The administration of this lucrative trade soon fell into the hands of ruthless leaders, known as reises, and these took on the title of Agha or Bey and became rulers of powerful military republics. At times, European states would seek the support of these robber powers against their current adversary, whilst others were prepared to pay a hefty indemnity to save their ships from being boarded and plundered.

xxxxxOver the years some attempts were made by European powers to knock out these pirate strongholds. In 1655, for example, a British fleet under the command of Admiral Robert Blake, attacked Tunis, and during the reign of Charles II numerous expeditions were despatched to teach the pirates a lesson. In the early 1680s the French attacked Algiers on two occasions. But these assaults were punitive by nature and never driven home. As a result, the pirates were active throughout the 18th century. Indeed, so serious did the situation become that, as we shall see, the Congress of Vienna of 1815 (G3c), which made the peace settlement at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, stressed the need to rid the seas of these plunderers, though this was not achieved until well into the 19th century.

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Barbary Pirates established their bases along the North African coast as early as Roman times, and by the 1500s had become a serious menace to shipping in the eastern Mediterranean. Emperor Charles V attempted to destroy them in 1535 (H8), and the defeat of the Ottoman Turks at the naval Battle of Lepanto in 1571 slowed down their activities for a time. However, during the reign of Murad IV (1623-1640) they combined their forces and, by using sailing boats instead of galleys, extended their attacks into the Atlantic, plundering ships and raiding coastal towns in England and elsewhere to capture slaves. Some countries paid them money to gain immunity for their merchant ships, others often sought their support in their wars against other states. A number of attempts were made to destroy their bases, but these attacks were never pressed home. As we shall see, it was not until the Congress of Vienna of 1815 (G3c) that the days of the Barbary Pirates became numbered.

xxxxxAs we have seen, with the defeat of the Turks at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, the Ottoman Empire began to show the first signs of decay, and matters were made worse in 1623 (J1) with the seizure of Baghdad by the Safavids of Iran under their leader Abbas I. The new Ottoman leader, however, Murad IV, put a temporary halt to the decline. By a set of draconian measures - his “Traditional Reforms” - he crushed all opposition at home, rebuilt his army, and, in 1638 recaptured Baghdad and drove the Safavids from Iraq. But with his death in 1640 his reforms did not last. As we shall see, one of his successors, the Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pasha, failing to take Vienna, was defeated at the Battle of Kahlenberg in 1683 (C2), and once again the empire began to lose ground.

xxxxxAs we have seen, by the end of the reign of Suleyman the Magnificent (1520-66), the Ottoman Empire, founded in about 1300, was beginning to show the first signs of decay. Five years later the defeat of the Turkish fleet at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 confirmed this decline in power, though the final collapse of this huge empire was still some years ahead - over three centuries in fact! Indeed, the Ottoman Turks recovered their mastery of the Mediterranean within a few years of Lepanto, but were then faced with a threat much nearer home, from the Safavid rulers of Iran.

xxxxxAs we have seen, by the end of the reign of Suleyman the Magnificent (1520-66), the Ottoman Empire, founded in about 1300, was beginning to show the first signs of decay. Five years later the defeat of the Turkish fleet at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 confirmed this decline in power, though the final collapse of this huge empire was still some years ahead - over three centuries in fact! Indeed, the Ottoman Turks recovered their mastery of the Mediterranean within a few years of Lepanto, but were then faced with a threat much nearer home, from the Safavid rulers of Iran.

xxxxxThe Safavid dynasty, established in 1499, had gained control of most of Iran by 1512. Two years later they were defeated at the Battle of Chaldiran by the Ottoman Turks and lost some of their territory, but by the end of the 16th century a brilliant leader had emerged, Shah Abbas I. Coming to power in 1588 he raised a highly proficient army over the next ten years and then felt able to take on the Ottoman Turks. He seized Tabriz and then in 1623 (J1), just a few years before his death, captured the treasured city of Baghdad. But his triumph was short lived. He died without an heir in 1629 (he had murdered all his next of kin!) and it was now left to the Ottomans to take the offensive under their new, able leader Murad IV.

xxxxxTough measures were required to bring a halt to the empire's decline, and Murad IV (illustrated) proved the man willing to provide and enforce them. Taking all power into his own hands, he ruthlessly crushed a rebellion in Asia Minor and then introduced a reign of terror to combat crime and corruption. By his so-called "Traditional Reforms", all criminals and those offending Islamic law and tradition were summarily punished by death, a policy which, according to some accounts, resulted in the execution of more than 100,000 people. The incompetent and corrupt also met the same fate, together with anyone who was in any way suspected of treason. In addition, meeting places, such as wine shops and coffee houses were closed to reduce the risk of sedition. By such draconian measures, efficiency was restored, particularly in the army. His reforms paid off. On the battlefield he waged war against Poland and then drove the Safavids out of Iraq, commanding his troops in person at the recapture of Baghdad in 1638. Once in charge of the city he presided over the massacre of its soldiers and citizens.

xxxxxTough measures were required to bring a halt to the empire's decline, and Murad IV (illustrated) proved the man willing to provide and enforce them. Taking all power into his own hands, he ruthlessly crushed a rebellion in Asia Minor and then introduced a reign of terror to combat crime and corruption. By his so-called "Traditional Reforms", all criminals and those offending Islamic law and tradition were summarily punished by death, a policy which, according to some accounts, resulted in the execution of more than 100,000 people. The incompetent and corrupt also met the same fate, together with anyone who was in any way suspected of treason. In addition, meeting places, such as wine shops and coffee houses were closed to reduce the risk of sedition. By such draconian measures, efficiency was restored, particularly in the army. His reforms paid off. On the battlefield he waged war against Poland and then drove the Safavids out of Iraq, commanding his troops in person at the recapture of Baghdad in 1638. Once in charge of the city he presided over the massacre of its soldiers and citizens.

xxxxxFollowing the death of Murad IV in 1640 - possibly caused by his liking for alcohol - his reforms did not survive for long. As we shall see, convinced of his army's strength, a future leader, the Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pasha, decided to invade central Europe. It was a bite more than he could chew. His brief siege of Vienna in 1683 (C2) totally failed following the defeat of his army at the Battle of Kahlenberg, and slowly but surely large areas of the empire were conquered by a new European Holy League.

C1-1625-1649-C1-1625-1649-C1-1625-1649-C1-1652-1649-C1-1625-1649-C1-1625-1649-C1

xxxxxIt was during the reign of Murad IV (1623-

xxxxxIt was during the reign of Murad IV (1623-

xxxxxAs we have seen, by the end of the reign of Suleyman the Magnificent (1520-

xxxxxAs we have seen, by the end of the reign of Suleyman the Magnificent (1520- xxxxxTough measures were required to bring a halt to the empire's decline, and Murad IV (illustrated) proved the man willing to provide and enforce them. Taking all power into his own hands, he ruthlessly crushed a rebellion in Asia Minor and then introduced a reign of terror to combat crime and corruption. By his so-

xxxxxTough measures were required to bring a halt to the empire's decline, and Murad IV (illustrated) proved the man willing to provide and enforce them. Taking all power into his own hands, he ruthlessly crushed a rebellion in Asia Minor and then introduced a reign of terror to combat crime and corruption. By his so-