THE BOSTON MASSACRE 1770 (G3a)

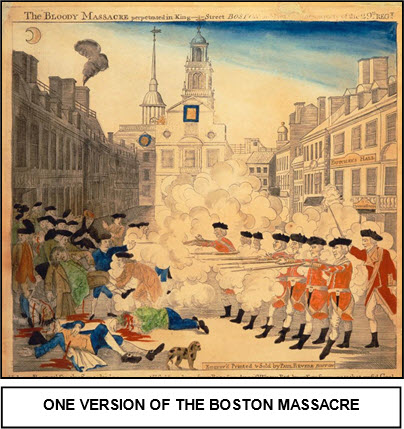

Despite the violent response to the Stamp Act in 1765, the British government had to reduce its financial burden. In 1767, avoiding an “internal tax”, it introduced “external duties” on a wide range of essential imports, such as paper, paint, glass and tea. The revenue raised, it explained, would pay for the officers of the crown working in the colonies. But the colonists would have none of it, and violent opposition flared up again. Eventually this led to an incident in Boston in 1770 in which British troops opened fire on a crowd and killed five civilians. To avoid a wider rebellion, the British government decided to repeal all these import duties except the one on tea. But all was not over. As we shall see, the port of Boston, which had already played a leading part in the opposition to taxation, was to take an even bigger role in 1773 with the famous Boston Tea Party, an event which was to be more than just a storm in a teacup.

xxxxxDespite the violent response to the imposition of the Stamp Act in 1765, the British government was committed and determined to find a means of reducing the country's financial burden. In 1767 Charles Townshend became Chancellor of the Exchequer and, assiduously avoiding an “internal tax” on the American colonies, imposed “external duties” on a wide range of essential imports, including lead, paint, paper, glass and tea. The revenue from such duties, it was made plain, was to pay for the officers of the crown who were working in the colonies. But neither this “reasonable” explanation, nor the subtle difference in the labelling of the tax, cut any ice with the colonists. Violent opposition, -

xxxxxAt Boston a public meeting drew up a non-

xxxxxThe city and port of Boston, it should be noted, had taken a leading part in the opposition to the mother country over taxation. During the disorders following the passing of the Stamp Act, for example, the governor's house was attacked and burnt down. Opposition there had been vigorously led by the  American politician Samuel Adams. There was then the “massacre” -

American politician Samuel Adams. There was then the “massacre” -

xxxxxBut, as we shall see, the city's greatest contribution to this mounting opposition towards the mother country was yet to come -

Acknowledgements

Massacre: by the American engraver Paul Revere (1734-

G3a-