THE BATTLE OF MARSTON MOOR July 1644 (C1)

Acknowledgements

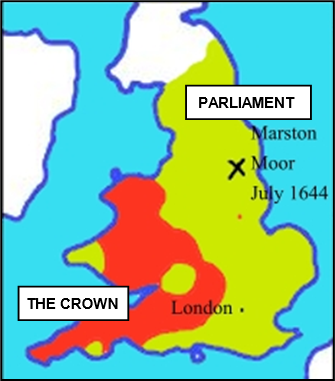

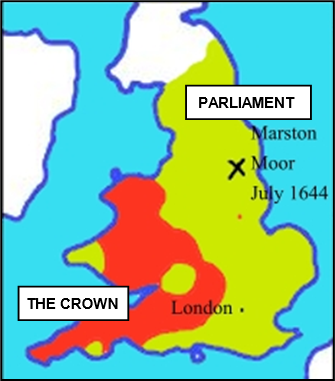

Map (England): licensed under Creative Commons – en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English+Civil+War. Marston Moor: by the British artist John Joseph Barker (1824-1904), date unknown – Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum, Gloucestershire, England. Prince Rupert: by the Dutch painter Gerrit van Honthorst (1592-1656), 17th century – collection of the Earl of Pembroke, Wilton House, Wiltshire, England. Edgehill: after the English military artist Harry Payne (1868-1940), illustrated in Hutchinson’s Story of the British Nation, 1920 – private collection.

xxxxxFollowing the indecisive Battle of Edgehill in 1642, the Royalists held the upper hand. They set up their headquarters at Oxford and even launched an attack upon London, but this had to be abandoned when the Parliamentarians made a deal with the Scottish Covenanters and put northern England in jeopardy. The Royalists responded by making peace with the Irish rebels and going on the offensive. In 1644, led by Prince Rupert, they attacked the Roundheads, then besieging York, and drove them on to Marston Moor. Here, however, they were counter-attacked by the parliamentary cavalry, supported on one wing by the “Ironsides”, a disciplined force under the inspiring leadership of Oliver Cromwell. The king’s central front was virtually destroyed and the Royalists fled the battle, Rupert only just managing to escape. They made a quick recovery but, as we shall see, in the next major encounter, the Battle of Naseby in 1645, Parliament’s New Model Army, raised in the meantime, was to have a decisive effect.

xxxxxFor about a year after the bloody but indecisive Battle of Edgehill in October 1642, the Royalists held the upper hand, increasing their control over Yorkshire in particular, and setting up the king's court and military headquarters at Oxford. Here in July Charles was joined by the Queen, returning from the  continent after raising much-needed cash by pawning some of the crown jewels. So confident were the king's forces at this stage, that an attack was planned upon London. A royalist force reached Turnham Green, just north of the capital, but the attack had to be abandoned when Parliament concluded an alliance with the Scottish Covenanters and put northern England in jeopardy. This alliance, forged on the promise that the Anglican Church would conform to the Presbyterian Church in Scotland, was a blow to royalist hopes. They responded by making peace with the Irish rebels, thus releasing troops for deployment on the mainland

continent after raising much-needed cash by pawning some of the crown jewels. So confident were the king's forces at this stage, that an attack was planned upon London. A royalist force reached Turnham Green, just north of the capital, but the attack had to be abandoned when Parliament concluded an alliance with the Scottish Covenanters and put northern England in jeopardy. This alliance, forged on the promise that the Anglican Church would conform to the Presbyterian Church in Scotland, was a blow to royalist hopes. They responded by making peace with the Irish rebels, thus releasing troops for deployment on the mainland

xxxxxBy now, one member of Parliament, the outspoken Oliver Cromwell, was emerging as a formidable leader both off and on the battlefield. During 1643 he devoted much time to training his regiment of cavalry, both in tactics and discipline, and, as a result, gained most of his home area, East Anglia, for Parliament. This mounted force then played a major part when the two sides met on Marston Moor in July 1644, just seven miles west of York. The opening rounds of the battle went to the Royalist forces. In June, under the command of the king's nephew, the outstanding soldier Prince Rupert of the Palatinate, the Cavaliers had forced the Roundheads to lift their siege of York and then had driven them back to Long Marston , seven miles to the west. Here, however, the parliamentary forces under Sir Thomas Fairfax, and a Scottish army led by the Earl of Leven, reformed, and the following month launched a surprise attack upon the Royalists. Cromwell's cavalry, operating on the left wing, drove headlong through Rupert's mounted force and then, regrouping on the move, turned to the right, encircling and virtually annihilating the king's central front. This action - in which Cromwell's cavalry earned the title of "the Ironsides" - proved decisive and the king's men fled the field - with Rupert forced to hide in a bean field to escape.

, seven miles to the west. Here, however, the parliamentary forces under Sir Thomas Fairfax, and a Scottish army led by the Earl of Leven, reformed, and the following month launched a surprise attack upon the Royalists. Cromwell's cavalry, operating on the left wing, drove headlong through Rupert's mounted force and then, regrouping on the move, turned to the right, encircling and virtually annihilating the king's central front. This action - in which Cromwell's cavalry earned the title of "the Ironsides" - proved decisive and the king's men fled the field - with Rupert forced to hide in a bean field to escape.

xxxxxFor the Royalists, Marston Moor was a humiliating defeat. They suffered heavy casualties, most of their artillery was captured, and they lost control of the north, one of their major strongholds. Furthermore, and perhaps most disturbing of all, they were now faced with a formidable opponent in the person of Oliver Cromwell, Parliament's new general. Nevertheless, soon after their defeat the Royalists were once again on the offensive and did, in fact, meet with a deal of success during the next few months, winning victories at Lostwithiel in Cornwall and at Newbury in Berkshire.

xxxxxIn the meantime, Sir Thomas Fairfax worked on forming a New Model Army, a highly-disciplined force made up of 11 regiments of horse, 12 regiments of foot, and 1,000 mounted infantrymen (known as "dragoons"). This army, over 20,000 strong, comprised of veterans from earlier armies, as well as men pressed into service from London, the south east, and the east. As we shall see, such a force was to prove its worth at the Battle of Naseby in 1645, the next major encounter in this bitter, costly struggle between Crown and Parliament.

C1-1625-1649-C1-1625-1649-C1-1625-1649-C1-1652-1649-C1-1625-1649-C1-1625-1649-C1

xxxxxPrince Rupert (1619-1692) of the Palatinate, the king’s nephew, having gained military experience in the Thirty Years’ War, proved of great value to the Royalist forces when he came to England in 1642. A daring cavalry commander, in the first phase of the civil war he captured Bristol and drove the Roundheads out of much of Lancashire. However, as we have seen, he suffered a major defeat at Marston Moor and, as we shall see, he failed again at Naseby in 1645. A few months later he surrendered Bristol to Parliament and, accused of treachery, was forced to leave England. He returned when Charles II was restored to the throne, and served as a naval commander in the Anglo-Dutch Wars before becoming the first governor of the Hudson Bay Company in Canada.

xxxxxPrince Rupert (1619-1682) was the king's nephew, being the third son of Frederick V (Elector Palatine of the Rhine) and Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of James I. For a short time - before being captured - he fought against the imperialists in the Thirty Years’ War, and the military experience he gained during this conflict stood him in good stead when he came to England in 1642 to support the royalist cause. High-spirited and daring, he showed exceptional ability as a cavalry officer, and was appointed commander of the king's cavalry at the age of 23. During the first eighteen months of the war he won a series of brilliant victories against the Roundheads - including the Battle of Edgehill and the capture of Bristol - and by June 1644 he had conquered most of Lancashire for the Royalists.

xxxxxPrince Rupert (1619-1682) was the king's nephew, being the third son of Frederick V (Elector Palatine of the Rhine) and Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of James I. For a short time - before being captured - he fought against the imperialists in the Thirty Years’ War, and the military experience he gained during this conflict stood him in good stead when he came to England in 1642 to support the royalist cause. High-spirited and daring, he showed exceptional ability as a cavalry officer, and was appointed commander of the king's cavalry at the age of 23. During the first eighteen months of the war he won a series of brilliant victories against the Roundheads - including the Battle of Edgehill and the capture of Bristol - and by June 1644 he had conquered most of Lancashire for the Royalists.

xxxxxHe suffered his first major defeat on the battlefield of Marston Moor, where the greater discipline shown by Cromwell's cavalry in the course of the fighting was a major factor in Parliament's success.  However, despite this failure, he was made Duke of Cumberland and Earl of Holderness, and in November 1644 was appointed commander-in-chief of the king's armies. In May 1645 he seized Leicester, but, as we shall see, a month later, at the Battle of Naseby, he suffered another serious defeat. Here, as on Marston Moor, his cavalry broke through the enemy's lines, but did not remain on the battlefield to take tactical advantage of the situation. The New Model Army was given time to regroup, and Cromwell's cavalry again won the day. Then in September he lost the support of his uncle when he surrendered Bristol to the Roundheads. Suspected of treachery, he was at once relieved of his command and, following the king's surrender to the Scots in 1646, was banished from England by Parliament.

However, despite this failure, he was made Duke of Cumberland and Earl of Holderness, and in November 1644 was appointed commander-in-chief of the king's armies. In May 1645 he seized Leicester, but, as we shall see, a month later, at the Battle of Naseby, he suffered another serious defeat. Here, as on Marston Moor, his cavalry broke through the enemy's lines, but did not remain on the battlefield to take tactical advantage of the situation. The New Model Army was given time to regroup, and Cromwell's cavalry again won the day. Then in September he lost the support of his uncle when he surrendered Bristol to the Roundheads. Suspected of treachery, he was at once relieved of his command and, following the king's surrender to the Scots in 1646, was banished from England by Parliament.

xxxxxHe was later reconciled with his uncle, and when Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660 he returned to England and served as a naval commander during the second and third Anglo-Dutch Wars. It was after this that he became the first governor of the Hudson Bay Company and, as a prominent shareholder, had a large tract of Canadian territory named Rupert's Land in his honour. A long term warrior in the service of the English Crown, his last years were spent at Windsor, and it is there that he died in 1682.

continent after raising much-

continent after raising much- , seven miles to the west. Here, however, the parliamentary forces under Sir Thomas Fairfax, and a Scottish army led by the Earl of Leven, reformed, and the following month launched a surprise attack upon the Royalists. Cromwell's cavalry, operating on the left wing, drove headlong through Rupert's mounted force and then, regrouping on the move, turned to the right, encircling and virtually annihilating the king's central front. This action -

, seven miles to the west. Here, however, the parliamentary forces under Sir Thomas Fairfax, and a Scottish army led by the Earl of Leven, reformed, and the following month launched a surprise attack upon the Royalists. Cromwell's cavalry, operating on the left wing, drove headlong through Rupert's mounted force and then, regrouping on the move, turned to the right, encircling and virtually annihilating the king's central front. This action - xxxxxPrince Rupert (1619-

xxxxxPrince Rupert (1619- However, despite this failure, he was made Duke of Cumberland and Earl of Holderness, and in November 1644 was appointed commander-

However, despite this failure, he was made Duke of Cumberland and Earl of Holderness, and in November 1644 was appointed commander-