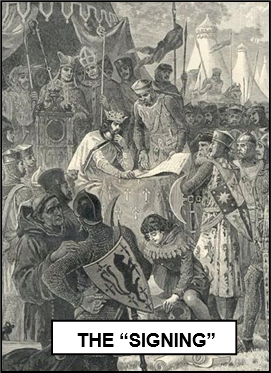

xxxxxThe Magna Carta was an attempt by barons and churchmen to reduce the power of the monarch, achieved, be it noted, at a time when the king's fortunes were at their lowest ebb, and the barons were in control of London! The document was accepted by John at a meeting at Runnymede in June 1215, but its 61 clauses had nothing new to say, they simply re-

THE MAGNA CARTA 1215 (JO)

xxxxxThe Magna Carta was the result, -

xxxxxThe Magna Carta was the result, -

xxxxxIn the minds of many people the Magna Carta has come to represent an important document in the common man's struggle for freedom. In fact, none of its 61 clauses, hammered out over five days, had anything new to offer, and many were concerned with minor matters related to the feudal system. Generally, they simply re-

xxxxxThe last clause of the document, and the most significant, established a Council of 25 barons which was authorised arbitrarily to organise a rebellion against the King should he fail to keep his promises. It was quickly in action. No sooner was Runnymede over than the agreement -

xxxxxThe last clause of the document, and the most significant, established a Council of 25 barons which was authorised arbitrarily to organise a rebellion against the King should he fail to keep his promises. It was quickly in action. No sooner was Runnymede over than the agreement -

xxxxxBut in the long term the Charter did have a significant value. It put in writing that there were limitations to royal power, and the king was not above the law. The subject (albeit only the freeman at this time) had certain rights of his own, and these must be respected. Such statements may have had little or no influence at the time or in the immediate future. Indeed, the Tudors and some Stuarts acted as if they had never heard of them. Furthermore, as feudalism went into decline so did the significance of the Charter. But these statements had been made, and they had been accepted. They were an aspiration and, later, an expectation, nothing more than that, but, nevertheless, the Magna Carta can be seen as the first small step towards the rights of the common man.

xxxxxFollowing the agreement at Runnymede copies of the Charter were sent throughout the land, each written on a piece of parchment about 10 to 15 inches in size. Four original copies still exist. There is one in both Salisbury and Lincoln cathedrals and two in the British Museum. The Charter was up-

xxxxxIncidentally, the Runnymede meadows where the Charter was agreed -

xxxxxThe nineteenth century English writer Rudyard Kipling wrote a poem about the signing of the Magna Carta in a work entitled What Sayeth the Reeds at Runnymede. One of the verses reads:

At Runnymede, at Runnymede

Your rights were won at Runneymede!

No freeman shall be fined or bound

Or dispossessed of freehold ground,

Except by lawful judgment found

And passed upon him by his peers.

Forget not after all these years

Charter signed at Runnymede.

Acknowledgement

The “Signing”: illustration from Cassell’s History of England, Century Edition, c1902, artist unknown.

JO-