FORMATION OF THE EAST INDIA COMPANIES

Acknowledgements

Map (The World): source unknown. Madras: etching by Dutch artist Jan van Ryne (1712-

ces.com/British+East+India+Company. Indiaman: date and artist unknown. Ternate: date and artist unknown. Map (Spice Islands): from imgsoup.com/1/Indonsian-

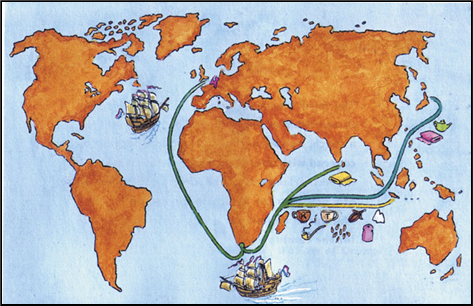

xxxxxThe opening of the sea route to India by Vasco da Gama in 1498 spawned a vast number of merchant adventurers bent on tapping wealth from the lucrative trade to be had with the Orient. Fortunes were to be made in the import of silk and cotton goods, indigo, saltpetre, tea and, above all, spices. At the beginning of the seventeenth century a number of seafaring nations of Western Europe formed government sponsored companies made up, for the most part, of these private traders. These companies were given extraordinary powers. Apart from creating their own fleet of ships, they were granted the right to form armies, and empowered to take over territory for the establishment of ports and trading posts. Having gained a commercial foothold, they then had the right to administer the area, levying taxes, administrating justice, making treaties and levying war, be it against the indigenous people or those European companies who sought to encroach upon their particular "patch". It was a European scramble for a highly profitable two-

xxxxxThe opening of the sea route to India by Vasco da Gama in 1498 spawned a vast number of merchant adventurers bent on tapping wealth from the lucrative trade to be had with the Orient. Fortunes were to be made in the import of silk and cotton goods, indigo, saltpetre, tea and, above all, spices. At the beginning of the seventeenth century a number of seafaring nations of Western Europe formed government sponsored companies made up, for the most part, of these private traders. These companies were given extraordinary powers. Apart from creating their own fleet of ships, they were granted the right to form armies, and empowered to take over territory for the establishment of ports and trading posts. Having gained a commercial foothold, they then had the right to administer the area, levying taxes, administrating justice, making treaties and levying war, be it against the indigenous people or those European companies who sought to encroach upon their particular "patch". It was a European scramble for a highly profitable two-

Including:

East India Companies:

English (British), Dutch,

French and Danish

L1-

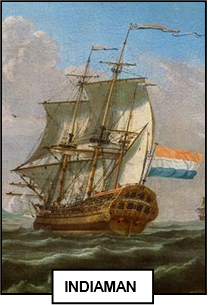

xxxxxThe Dutch East India Company followed in 1602, chartered by the States General (parliament) of the Netherlands, and with a huge initial capital of £540,000. Granted a monopoly of Dutch trade in the Indonesian archipelago it quickly expanded its operations, reaching as far as the lucrative markets of India, China and Japan. Pictured here is a typical Dutch East Indiaman. Like their English counterpart, these were huge and well-

xxxxxThe Dutch East India Company followed in 1602, chartered by the States General (parliament) of the Netherlands, and with a huge initial capital of £540,000. Granted a monopoly of Dutch trade in the Indonesian archipelago it quickly expanded its operations, reaching as far as the lucrative markets of India, China and Japan. Pictured here is a typical Dutch East Indiaman. Like their English counterpart, these were huge and well-

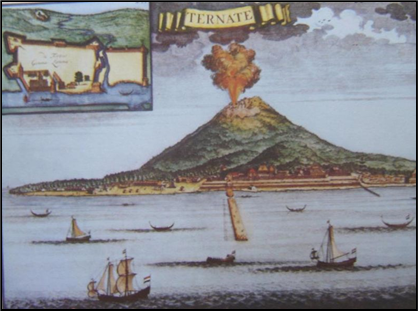

xxxxxAt the peak of its power, the company could boast of 40 warships, 150 merchantmen, and 10,000 soldiers. Trading was on a regular basis, and for most of the seventeenth century annual dividends never fell below 10% and, at times, reached above 60%. The main port of destination for the merchant ships was Batavia (Jakarta) on the island of Java, but the long voyage was greatly eased in 1652, following the founding of a staging post at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa. The company flourished well into the 18th century, but wars with its competitors -

xxxxxAt the peak of its power, the company could boast of 40 warships, 150 merchantmen, and 10,000 soldiers. Trading was on a regular basis, and for most of the seventeenth century annual dividends never fell below 10% and, at times, reached above 60%. The main port of destination for the merchant ships was Batavia (Jakarta) on the island of Java, but the long voyage was greatly eased in 1652, following the founding of a staging post at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa. The company flourished well into the 18th century, but wars with its competitors -

xxxxxThe Dutch East India Company was established in 1602 and, in addition to the spice trade in the Indonesian archipelago, opened up markets in India, China and Japan. They later stopped the English from gaining a hold on the lucrative spice trade, and seized Portuguese possessions in the Far East. The company flourished, and at the peak of its power had 150 merchantmen, guarded by 40 warships and 10,000 soldiers. Their main port was Batavia (Jakarta), and in 1652 a staging post was set up at the Cape of Good Hope. In the late 18th century, however, wars with rivals, general mismanagement, and widespread corruption brought about a decline, and in 1798 the Dutch government took over the company.

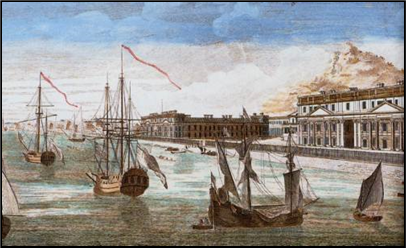

xxxxxThe French were much later in the field. The French East India Company was established in 1664 with the prior aim of competing with the English and Dutch. They set up trading posts in India at Surat and Pondicherry (illustrated), and sent trading missions to China and Iran. In 1719, however, the company was amalgamated with the French colonial company trading in Africa and the Americas. This marked the beginning of its downfall. It now shared in a number of disasters, none of its own making. In the 1730s, following the collapse of the Mississippi scheme, the company lost its slave trade out of Africa, its general trade with Louisiana, and its coffee trade with the Americas.

xxxxxThe French were much later in the field. The French East India Company was established in 1664 with the prior aim of competing with the English and Dutch. They set up trading posts in India at Surat and Pondicherry (illustrated), and sent trading missions to China and Iran. In 1719, however, the company was amalgamated with the French colonial company trading in Africa and the Americas. This marked the beginning of its downfall. It now shared in a number of disasters, none of its own making. In the 1730s, following the collapse of the Mississippi scheme, the company lost its slave trade out of Africa, its general trade with Louisiana, and its coffee trade with the Americas.

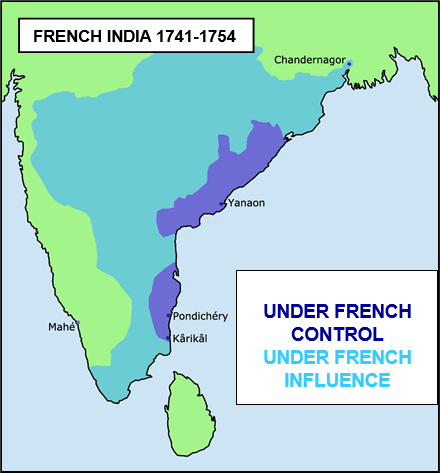

xxxxxMeanwhile, and in contrast, trade in India flourished until the 1750s, when the inevitable power struggle with the British came to a head. The French negotiated with local rulers in an attempt to undermine British influence and gain local support, but a series of defeats at the hands of the British -

xxxxxHaving failed to obtain a share in the markets of the Far East during the seventeenth century, the Danish East India Company was established in 1729 by King Frederick IV. At first, its operations in India proved most successful, but with the spread of British influence growing ever wider, the company found it hard to compete. When, in 1801, the British crippled the Danish fleet off Copenhagen, it went out of business, and its trading posts in India were sold to the British in 1845.

xxxxxThe French were much later in the field. The French East India Company was established in 1664. They set up trading posts in India at Surat and Pondicherry, and also sent trading missions to China and Iran. In 1719, however, the company was merged with the company trading in Africa and the Americas, and was thus obliged to share in the collapse of the Mississippi scheme, which included the loss of its slave trade out of Africa, and of its coffee trade in the Americas. Meanwhile trade in India flourished until the inevitable clash with the British. Defeats were suffered at Arcot in 1751 and Wandewash in 1760, and the loss of Pondicherry, the capital of French India, the following year, marked the end of the company. Trading ceased eight years later.

xxxxxThe English (later British) East India Company was chartered in 1600, and was destined to play a major part in the government of India for more than two centuries. Early on, attempts were made to break into the spice trade, but later the Malay archipelago and the Moluccas were conceded to the Dutch. By 1652 over 20 posts or “factories” had been set up in India, and with the defeat of the French in the 18th century -

xxxxxIt was in 1600 that the English (later British) East India Company was chartered by Queen Elizabeth and granted the monopoly of the trade between England and the Far East. Its initial capital was £70,000. Of all the East India Companies, this one proved of the greatest consequence, if only because of the major part it came to play in the government of the vast land of India over a period of more than two centuries. During the early years, trading posts were set up in the Malay archipelago and the Moluccas to break into the spice trade, but following the execution of ten company agents on the island of Amboina in 1632 -

xxxxxIt was in 1600 that the English (later British) East India Company was chartered by Queen Elizabeth and granted the monopoly of the trade between England and the Far East. Its initial capital was £70,000. Of all the East India Companies, this one proved of the greatest consequence, if only because of the major part it came to play in the government of the vast land of India over a period of more than two centuries. During the early years, trading posts were set up in the Malay archipelago and the Moluccas to break into the spice trade, but following the execution of ten company agents on the island of Amboina in 1632 -

xxxxxFor the most part, efforts were now concentrated on India (though trade was later extended to China), and by 1652 there were over 20 factories (trading posts) on the sub-

xxxxxFor the most part, efforts were now concentrated on India (though trade was later extended to China), and by 1652 there were over 20 factories (trading posts) on the sub-

xxxxxFrom then on, however, a series of moves were taken by the home government to bring this vast land under the authority of the Crown. A Governor-