JOHN HARRISON 1693 - 1776 (W3, AN, G1, G2, G3a)

After nearly fifty years of research, the English clockmaker John Harrison invented the first practical chronometer. Tested over a voyage lasting three months, it was accurate to within 5 seconds. This provided the means - long sought - to determine longitude during long sea voyages. For this vital navigational aid, produced in 1762, he won a prize from the Board of Longitude, but only after the intervention of Parliament and the King. The award was not paid in full until 1773, 3 years before his death.

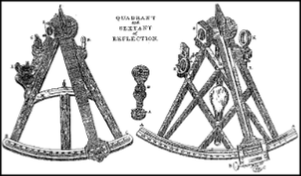

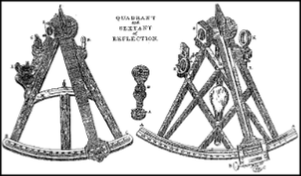

xxxxxThe English clockmaker John Harrison was born in Foulby, Yorkshire, and began work as a carpenter in his father's workshop at a young age. It was around this time that serious efforts were being made to find a more accurate means of determining longitude at sea. This had been a long term problem. One solution put forward and in use at this time was the lunar-distance method in which angles taken by an octant (and, later, a sextant) were compared with the predicted lunar distances in a yearly almanac. This enabled the navigator to determine the Greenwich Time when the observation was made, and thereby arrive at the ship's longitude. But it was something of a hit and miss affair, especially in poor weather conditions. The second and more reliable solution depended on a mechanical timekeeper which would remain accurate over long periods at sea, and would not be affected by changes in temperature. As we have seen, in 1657 (CW) the Dutchman Christiaan Huygens had invented the pendulum clock, but this was not particularly accurate and it had not been adapted for use aboard a vessel.

xxxxxThe English clockmaker John Harrison was born in Foulby, Yorkshire, and began work as a carpenter in his father's workshop at a young age. It was around this time that serious efforts were being made to find a more accurate means of determining longitude at sea. This had been a long term problem. One solution put forward and in use at this time was the lunar-distance method in which angles taken by an octant (and, later, a sextant) were compared with the predicted lunar distances in a yearly almanac. This enabled the navigator to determine the Greenwich Time when the observation was made, and thereby arrive at the ship's longitude. But it was something of a hit and miss affair, especially in poor weather conditions. The second and more reliable solution depended on a mechanical timekeeper which would remain accurate over long periods at sea, and would not be affected by changes in temperature. As we have seen, in 1657 (CW) the Dutchman Christiaan Huygens had invented the pendulum clock, but this was not particularly accurate and it had not been adapted for use aboard a vessel.

xxxxxIn an attempt to solve this problem, in 1714 the British government's Board of Longitude offered a reward of up to £20,000 to anyone who could produce an instrument which would keep time to within three seconds a day. In practical terms, this degree of accuracy meant that a navigator, by comparing the time at Greenwich (0 degree longitude) with his local time, would then be able to calculate his ship's east-west position to within 30 miles. It was a challenge that the young John Harrison took up. The following year he built an eight-day clock entirely out of wood, and then, having always had an interest in things mechanical, he turned his hand to improving the mechanism. After twenty years he produced his first "marine timekeeper" (illustrated), a clock which weighed 72 lbs and did not prove up to the task. In fact it was another twenty years and three timepieces later before he was ready to submit his fourth "chronometer" - as it came to be called - to the Board's scrutiny.

xxxxxIn an attempt to solve this problem, in 1714 the British government's Board of Longitude offered a reward of up to £20,000 to anyone who could produce an instrument which would keep time to within three seconds a day. In practical terms, this degree of accuracy meant that a navigator, by comparing the time at Greenwich (0 degree longitude) with his local time, would then be able to calculate his ship's east-west position to within 30 miles. It was a challenge that the young John Harrison took up. The following year he built an eight-day clock entirely out of wood, and then, having always had an interest in things mechanical, he turned his hand to improving the mechanism. After twenty years he produced his first "marine timekeeper" (illustrated), a clock which weighed 72 lbs and did not prove up to the task. In fact it was another twenty years and three timepieces later before he was ready to submit his fourth "chronometer" - as it came to be called - to the Board's scrutiny.

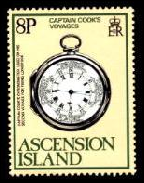

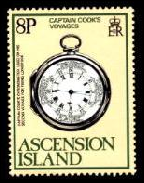

xxxxxBased on his long years of research, this final version incorporated a balance spring made up of a strip of two metals - each with a different rate of expansion to reduce the effect of temperature changes - and a backup clockwork mechanism to prevent any running down of the driving force. Only 13 cms in diameter and looking like a large pocket watch (illustrated), it proved astonishingly efficient. In 1762, after a sea voyage to the West Indies and back lasting three months, it was only 5 seconds slow! This clearly met the Board's specifications, but its cost of production and the delicate nature of its mechanism kept it from immediate use. Furthermore, despite nearly fifty years of research, the Board - playing hard to be convinced - only awarded him £2,500. It was only after the intervention of Parliament and the King himself that in 1773 he was eventually given the full amount, just three years before his death. Later improvements, notably by the Swiss clockmaker Ferdinand Berthoud (1727-1807), led to the modern chronometer, used successfully from the middle of the 19th century.

xxxxxBased on his long years of research, this final version incorporated a balance spring made up of a strip of two metals - each with a different rate of expansion to reduce the effect of temperature changes - and a backup clockwork mechanism to prevent any running down of the driving force. Only 13 cms in diameter and looking like a large pocket watch (illustrated), it proved astonishingly efficient. In 1762, after a sea voyage to the West Indies and back lasting three months, it was only 5 seconds slow! This clearly met the Board's specifications, but its cost of production and the delicate nature of its mechanism kept it from immediate use. Furthermore, despite nearly fifty years of research, the Board - playing hard to be convinced - only awarded him £2,500. It was only after the intervention of Parliament and the King himself that in 1773 he was eventually given the full amount, just three years before his death. Later improvements, notably by the Swiss clockmaker Ferdinand Berthoud (1727-1807), led to the modern chronometer, used successfully from the middle of the 19th century.

xxxxxIncidentally, Captain Cook took a copy of his winning timepiece on his second voyage, and dubbed it "our trusty friend". Harrison's marine instruments can be seen at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, just outside London. ……

xxxxxIncidentally, Captain Cook took a copy of his winning timepiece on his second voyage, and dubbed it "our trusty friend". Harrison's marine instruments can be seen at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, just outside London. ……

xxxxx…… Harrison’s accurate chronometer enabled the Greenwich meridian to be fixed by triangulation in 1787. However, it was almost a century later (1884) before this line was accepted internationally as the universal prime meridian. ……

xxxxx…… As noted earlier, the English clockmaker George Graham played a part in the success of this chronometer. Around 1730 he loaned Harrison £200 so that he could start work on his project. ……

xxxxx…… Withxregard to the lunar method for finding longitude at sea - which was no longer used once the chronometer had been introduced - it was the English inventor John Hadley (1682-1744) who in 1730 or thereabouts designed an instrument in the form of an octant (eighth of a circle) to measure the required angles. In 1757 this was extended to a sixth of a circle by a British naval officer named John Campbell and this came to be known as a "sextant".

xxxxx…… Withxregard to the lunar method for finding longitude at sea - which was no longer used once the chronometer had been introduced - it was the English inventor John Hadley (1682-1744) who in 1730 or thereabouts designed an instrument in the form of an octant (eighth of a circle) to measure the required angles. In 1757 this was extended to a sixth of a circle by a British naval officer named John Campbell and this came to be known as a "sextant".

Acknowledgements

Harrison: detail, by the British artist Thomas King (died c1796), 1767 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Marine Timekeeper: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Watch: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Sextant: date and artist unknown.

G3a-1760-1783-G3a-1760-1783-G3a-1760-1783-G3a-1760-1783-G3a-1760-1783-G3a

xxxxxThe English clockmaker John Harrison was born in Foulby, Yorkshire, and began work as a carpenter in his father's workshop at a young age. It was around this time that serious efforts were being made to find a more accurate means of determining longitude at sea. This had been a long term problem. One solution put forward and in use at this time was the lunar-

xxxxxThe English clockmaker John Harrison was born in Foulby, Yorkshire, and began work as a carpenter in his father's workshop at a young age. It was around this time that serious efforts were being made to find a more accurate means of determining longitude at sea. This had been a long term problem. One solution put forward and in use at this time was the lunar- xxxxxIn an attempt to solve this problem, in 1714 the British government's Board of Longitude offered a reward of up to £20,000 to anyone who could produce an instrument which would keep time to within three seconds a day. In practical terms, this degree of accuracy meant that a navigator, by comparing the time at Greenwich (0 degree longitude) with his local time, would then be able to calculate his ship's east-

xxxxxIn an attempt to solve this problem, in 1714 the British government's Board of Longitude offered a reward of up to £20,000 to anyone who could produce an instrument which would keep time to within three seconds a day. In practical terms, this degree of accuracy meant that a navigator, by comparing the time at Greenwich (0 degree longitude) with his local time, would then be able to calculate his ship's east- xxxxxBased on his long years of research, this final version incorporated a balance spring made up of a strip of two metals -

xxxxxBased on his long years of research, this final version incorporated a balance spring made up of a strip of two metals - xxxxxIncidentally, Captain Cook took a copy of his winning timepiece on his second voyage, and dubbed it "our trusty friend". Harrison's marine instruments can be seen at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, just outside London. ……

xxxxxIncidentally, Captain Cook took a copy of his winning timepiece on his second voyage, and dubbed it "our trusty friend". Harrison's marine instruments can be seen at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, just outside London. …… xxxxx…… Withxregard to the lunar method for finding longitude at sea -

xxxxx…… Withxregard to the lunar method for finding longitude at sea -