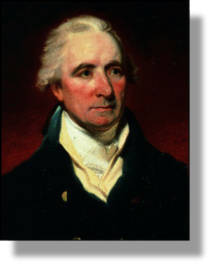

HENRY GRATTAN 1746 - 1820 (G2, G3a, G3b, G3c)

xxxxxThe Treaty of Limerick which followed the Protestant victory at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 (W3) was not a harsh settlement, but within a few years the Catholics had lost all their civic rights again and the English government, still in control of Irish affairs, had seriously restricted the island’s trading rights. With the coming of the American War of Independence in 1775, however, the Protestants, supported by their own defence force, the Irish Volunteers, and led by an able lawyer named Henry Grattan, forced the British government to make concessions. Trading restrictions were eased, some anti-

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Treaty of Limerick, which followed the victory of William III over James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 (W3), was not a particularly harsh settlement. Roman Catholics retained a measure of religious freedom and the land they had held under Charles II was restored to them. However, within a short while the Irish parliament had re-

xxxxxThe severe measures introduced against Irish commerce and industry at that time -

xxxxxThe severe measures introduced against Irish commerce and industry at that time -

xxxxxThe Irish statesman Henry Grattan (illustrated) was the man who emerged to champion this cause. He was born in Dublin, educated at Trinity College, and became a member of the Irish Parliament in 1775. A brilliant orator, he quickly became the principal leader of the nationalist movement. Discreetly but firmly supported by the Irish Volunteers, lurking in the background, he demanded free trade and, in 1780, legislative independence for Ireland. In fact the British parliament, concerned about the military situation in Ireland, felt it wise to make a favourable response. It repealed significant parts of Poynings’ Law, conceded parliamentary independence, and, by the Catholic Relief Act of 1782, removed much of the anti-

xxxxxThe Irish statesman Henry Grattan (illustrated) was the man who emerged to champion this cause. He was born in Dublin, educated at Trinity College, and became a member of the Irish Parliament in 1775. A brilliant orator, he quickly became the principal leader of the nationalist movement. Discreetly but firmly supported by the Irish Volunteers, lurking in the background, he demanded free trade and, in 1780, legislative independence for Ireland. In fact the British parliament, concerned about the military situation in Ireland, felt it wise to make a favourable response. It repealed significant parts of Poynings’ Law, conceded parliamentary independence, and, by the Catholic Relief Act of 1782, removed much of the anti-

xxxxxThus while the concessions made by the British government in 1782 were quite substantial, they did not go far enough to satisfy ardent patriots like the Irish lawyer Wolfe Tone. For them, the coming of the French Revolution in 1789 made a call to arms inevitable. Societies of United Irishmen were formed in the early 1790s and, opposed by the British, became dedicated to securing complete Irish independence. As we shall see, they were to take up arms in 1798 (G3b).

xxxxxMeanwhile in England the concessions granted to Roman Catholics by the Catholic Relief Act of 1778 alarmed and angered Protestants. An unstable, fanatical character by the name of Lord George Gordon (1751-

xxxxxMeanwhile in England the concessions granted to Roman Catholics by the Catholic Relief Act of 1778 alarmed and angered Protestants. An unstable, fanatical character by the name of Lord George Gordon (1751-

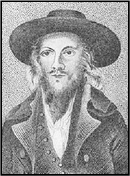

xxxxxIncidentally, Gordon, third son of the Duke of Gordon, was later convicted of libeling the Queen of France and the French ambassador in London. Ironically, in January 1788 he was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment in Newgate, the prison badly damaged during the riots. By all accounts he led such a comfortable life there that, when his five years were up and he could find no one to vouch for his good conduct, he was happy to stay on! He died of typhoid fever that same year. The portrait shows him after his conversion to Judaism in 1787. ……

xxxxxIncidentally, Gordon, third son of the Duke of Gordon, was later convicted of libeling the Queen of France and the French ambassador in London. Ironically, in January 1788 he was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment in Newgate, the prison badly damaged during the riots. By all accounts he led such a comfortable life there that, when his five years were up and he could find no one to vouch for his good conduct, he was happy to stay on! He died of typhoid fever that same year. The portrait shows him after his conversion to Judaism in 1787. ……

xxxxx…… The Gordon Riots -

Acknowledgements

Dublin: colour print from an original by the English portrait painter Francis Wheatley (1747-

G3a-

Including:

The Gordon Riots