THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

1775 -

THE FRANCO-

and the WAR AT SEA

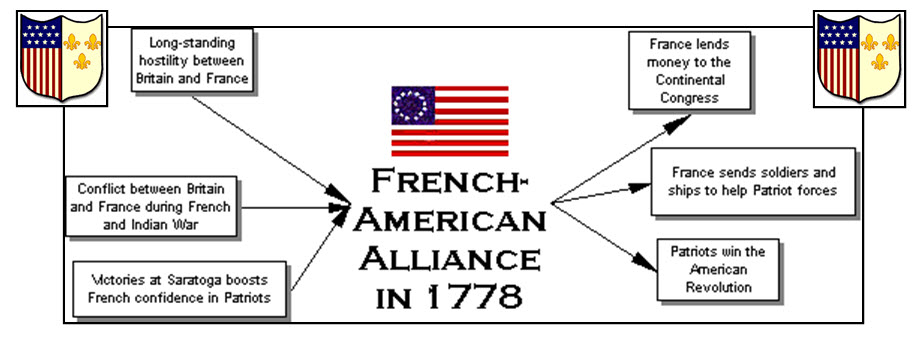

xxxxxThe resounding victory of the Colonists at the Battles of Saratoga in 1777, plus the fact that the British were known to be wanting a peace settlement, brought the French into the war in 1778. They had given arms and ammunition unofficially since the conflict began, but now they prepared their navy and army for a full-

xxxxxAs early as 1776 the Continental Congress had formed a three-

xxxxxIt would be difficult to exaggerate the importance to the colonists of France's entry into the war. It was, first and foremost perhaps, an enormous psychological boost to the independence movement. And quite apart from the increase this was to bring in troops and arms, it meant that the British fleet would be challenged not only on the high seas, but also in the North American coastal waters where Britain most needed to rule the waves. As we shall see, naval power was to prove a significant factor in the final victory of the colonists at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781.

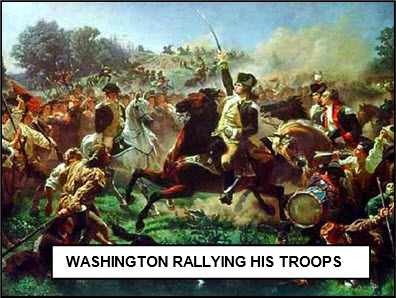

xxxxxAsxa result of the French decision, in 1778 the British decided to concentrate their forces around New York City and to send reinforcements to their possessions in the Caribbean. Consequently their new commander, General Sir Henry Clinton, withdrew his army from Philadelphia and began the march across New Jersey. It was an opportunity not to be missed. Washington, leaving his winter quarters at Valley Forge, caught up with the British at Monmouth (now Freehold) in June 1778. In the battle that followed (illustrated), the largest artillery encounter of the war, neither side got the upper hand, but the colonists, having undergone extensive training during the winter months, acquitted themselves well and gained a moral victory. The British eventually reached New York and Washington took up positions outside the city. Meanwhile, stalemate continued in the west, though Indian tribes, for the most part loyal to George III as their "great white father", continued to pose a constant threat to the frontier communities. The Cherokee and the Iroquois, in particular, frequently clashed with the patriot militia.

xxxxxAsxa result of the French decision, in 1778 the British decided to concentrate their forces around New York City and to send reinforcements to their possessions in the Caribbean. Consequently their new commander, General Sir Henry Clinton, withdrew his army from Philadelphia and began the march across New Jersey. It was an opportunity not to be missed. Washington, leaving his winter quarters at Valley Forge, caught up with the British at Monmouth (now Freehold) in June 1778. In the battle that followed (illustrated), the largest artillery encounter of the war, neither side got the upper hand, but the colonists, having undergone extensive training during the winter months, acquitted themselves well and gained a moral victory. The British eventually reached New York and Washington took up positions outside the city. Meanwhile, stalemate continued in the west, though Indian tribes, for the most part loyal to George III as their "great white father", continued to pose a constant threat to the frontier communities. The Cherokee and the Iroquois, in particular, frequently clashed with the patriot militia.

xxxxxIn the south, however, there was a deal of action, led by the British. The southern states, it was considered, were more loyal to the Crown, as well as being of more value commercially. In December 1778 and January 1779 troops from New York and Florida occupied Georgia and, later in the year, Franco-

xxxxxNotxhelping the rebel cause at this time was a number of near mutinies within the ranks of the Continental Army over poor pay and conditions (put down by local militia), and the defection of one of its most able generals Benedict Arnold, a veteran of the Saratoga campaign. Grieved at what he saw as a lack of recognition, in 1780 he attempted to betray West Point to the British. When the plan misfired, he had to make his escape and join the ranks of his former enemy. But despite these internal troubles, and the string of British victories, the rebel cause was by no means lost. Whilst often at a disadvantage in pitched battles, the guerrilla tactics used by the frontiersmen or “Overmountain Men” (here illustrated), continued unabated and seriously hampered their enemy's movements.

xxxxxNotxhelping the rebel cause at this time was a number of near mutinies within the ranks of the Continental Army over poor pay and conditions (put down by local militia), and the defection of one of its most able generals Benedict Arnold, a veteran of the Saratoga campaign. Grieved at what he saw as a lack of recognition, in 1780 he attempted to betray West Point to the British. When the plan misfired, he had to make his escape and join the ranks of his former enemy. But despite these internal troubles, and the string of British victories, the rebel cause was by no means lost. Whilst often at a disadvantage in pitched battles, the guerrilla tactics used by the frontiersmen or “Overmountain Men” (here illustrated), continued unabated and seriously hampered their enemy's movements.

xxxxxIn October 1780, for example, a force of 900 frontiersmen from North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia -

xxxxxIncidentally, because of the extremely harsh conditions endured by Washington's troops over the winter of 1777-

xxxxxIncidentally, because of the extremely harsh conditions endured by Washington's troops over the winter of 1777-

xxxxx...... In order to keep up his men's morale during these appalling winter conditions, Washington ordered that the first issue of The American Crisis, a pamphlet written by the Anglo-

xxxxx…… The Marquis de Lafayette who, as we shall see, was to play a prominent role in the French Revolution, took command of both French and American troops at the Battle of Yorktown. Known as “America’s Marquis”, he was made an honorary citizen of the newly independent United States in 1784. Later, one mountain and towns in four states were named after him!

Acknowledgements

Outline: easynotecards.com, Ganske Publishing Group. Monmouth: by the German/American painter Emanuel Leutze (1816-

G3a-

Including:

Valley Forge,

John Paul Jones

and

David Bushnell

xxxxxAs we have seen, the defeat of the royalist forces at the Battles of Saratoga in 1777 was a serious blow to the forces of the crown. In the south, Washington had been badly mauled by the end of the year. Despite some surprise victories, he had been pushed out of New York by General Howe, defeated at Brandywine Creek and seen Philadelphia fall to the enemy in September 1777. In the north, however, it was a very different story. The defeat and capitulation of an entire army under the command of General Burgoyne was nothing short of a disaster, and it had significant international repercussions. Up to this point the French had remained neutral officially, but had been secretly aiding the American rebels with money and material. Now, convinced that the colonists had the will to win their war of independence, and hearing rumours that Britain was anxious for a peace settlement, France came out fighting.

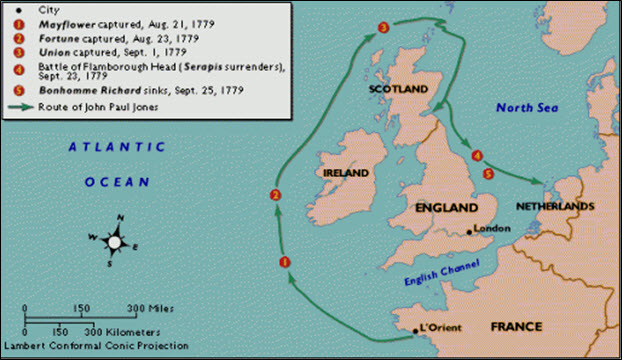

xxxxxAlthough Britain ruled the waves, the War at Sea was not without incident in the opening years of the war. The Continental Navy was established in October 1775 and, whilst small in number, caused havoc not only in the coastal waters along the North American coast, but also around the shores of Britain. The American hero John Paul Jones was but one of a number of captains who by 1777 had captured 560 vessels and their crews. This number had almost trebled by the end of the war. But the entry of France into the war in 1778 (followed by Spain in 1779 and the Netherlands in 1780) was the real threat to British sea power. Britain sent naval support to Gibraltar and the West Indies -

xxxxxIn the opening years of the American War of Independence, the War at Sea had been limited, but it was not without incident. The Continental Navy was established in October 1775, but its number of ships was small -

xxxxxIn the opening years of the American War of Independence, the War at Sea had been limited, but it was not without incident. The Continental Navy was established in October 1775, but its number of ships was small - quadron of four ships in August 1779, and within the space of a few weeks had captured 17 enemy merchant ships off the British coast. Then towards the end of September he dared to attack a British man-

quadron of four ships in August 1779, and within the space of a few weeks had captured 17 enemy merchant ships off the British coast. Then towards the end of September he dared to attack a British man-

xxxxxBut his was not the only American ship in British waters. A large number were operating in the same area, and by 1777 they had captured 560 British vessels and their crews. This number had probably trebled by the end of the war. Little wonder that British merchants were eager to see an end to hostilities before hostilities put an end to them.

xxxxxThe entrance of France into the war in 1778, followed by Spain in 1779, posed a serious threat to Britain's mastery of the seas, and questioned Britain's ability to defend England against possible invasion, support a full-

xxxxxIn the meantime, as a direct result of British naval weakness, in 1778 a French fleet had left Toulon and successfully reached New York, and in a battle off Ushant in July of that year, the British navy had put up a poor performance and let slip the Brest fleet. It was ships from this fleet which conveyed General Rochambeau's army to North America, and also provided the French squadron which, under the command of the Comte de Grasse, was summoned to Chesapeake Bay. Both these land and naval forces played a vital part in the blockade of Yorktown and the British surrender.

xxxxxNonetheless, the British managed to send reinforcements to Gibraltar -

xxxxxIncidentally, the Bonhomme Richard sank after its encounter with the Serapis in September 1779. Towards the end of the 20th century, divers searching off Flamborough Head, on the east coast of England, discovered what is believed to be its wreckage.

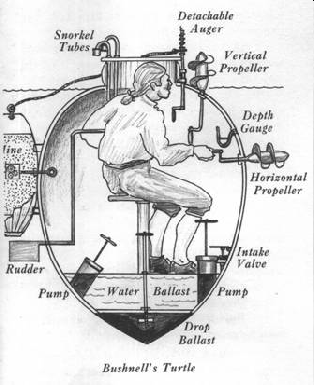

xxxxxThe American War of Independence witnessed the use of the first American submarine. Constructed of wood by the American inventor David Bushnell (1740-

xxxxxThe American War of Independence witnessed the use of the first American submarine. Constructed of wood by the American inventor David Bushnell (1740-

xxxxxUnfortunately for Bushnell, and the rebel cause, the idea did not work. Several attempts were made against British warships in 1776, but though the Turtle proved capable as a crude form of submarine, it became far too difficult to control the movement of the vessel under water. Nevertheless, General Washington gave Bushnell a commission in the engineers, and he ended up in command of the Army Corps of Engineers at West Point.

xxxxxHe is sometimes called the "father of the submarine", but, as we have seen, an attempt at making a submarine was made much earlier by the Dutch inventor Cornelius van Drebbel in 1620 (J1). It would be true to say, however, that Bushnell was the first to make and employ a submarine as an instrument of war. And, as we shall see, his version was to be greatly improved upon by his fellow countryman Robert Fulton in 1801 (G3b).