Including:

The English

Reformation

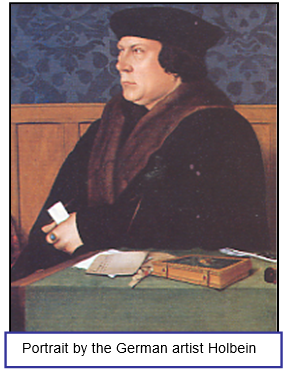

THOMAS CROMWELL c1485 -

xxxxxA man of humble birth, Thomas Cromwell began working for Thomas Wolsey in 1510, and when the cardinal fell from power in 1529, gradually took his place. He was made Chancellor of the Exchequer four years later and became advisor to the king in 1534. Then, together with Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, he worked on the legislation to make the English church fully independent of Rome and, by the Act of Supremacy, put Henry VIII at its head. Work was also begun on the dissolution of the monasteries, and this brought much wealth to the crown. In 1539, however, as part of his foreign policy, he arranged a marriage between the king and Anne of Cleves. This proved a disastrous match, and Cromwell paid the price. He was accused of treason, condemned without trial, and beheaded.

xxxxxFor a man born of humble origin, Thomas Cromwell had an astonishing rise to political power. He was born in Putney, near London, the son of an inn keeper, and spent his early years wandering about on the continent. He served in the French army for a time and also tried his hand as a trader. Returning to England in about 1510 he entered the service of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey as his solicitor, and this proved the making of him. He became a confidential advisor to the Cardinal, who, impressed by his remarkable ability, helped him to become a member of parliament.

xxxxxFor a man born of humble origin, Thomas Cromwell had an astonishing rise to political power. He was born in Putney, near London, the son of an inn keeper, and spent his early years wandering about on the continent. He served in the French army for a time and also tried his hand as a trader. Returning to England in about 1510 he entered the service of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey as his solicitor, and this proved the making of him. He became a confidential advisor to the Cardinal, who, impressed by his remarkable ability, helped him to become a member of parliament.

xxxxxFollowing Wolsey’s fall from power in 1529, Cromwell attached himself to the royal court where he soon became an advisor to the king himself. From then on his rise to power was nothing short of meteoric. He was appointed to the Privy Council in 1531, became Chancellor of the Exchequer two years later, and then, as secretary to the king in 1534, virtually became the director of government policy. Together with Thomas Cranmer, who as Archbishop of Canterbury had secured the king’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon, Cromwell set about drafting the legislation that was to make the English church fully independent of Rome.

xxxxxIn 1534, by the Act of Supremacy, he had the king appointed supreme head of the Church, thus making inevitable the break with Rome. He then passed legislation to ensure that every church was provided with an English bible, and in 1536, acting on the king’s orders, embarked on the dissolution of the monasteries, confiscating their considerable wealth and property. This programme, competently carried out and completed in 1540, included, among its many acts of vandalism, the desecration of the shrine of Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral. Meanwhile, it must be added, he made a number of much-

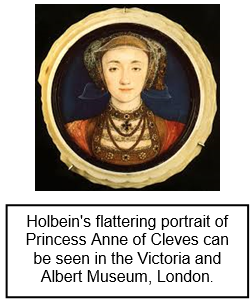

xxxxxIn 1539, however, he made a fatal error of judgement  and his fall from power proved as swift as his rise to it. In order to form an alliance with German Protestant princes against two major continental powers, France and the Holy Roman Empire, he arranged a marriage between the King and Anne of Cleves. Holbein, the court painter, was sent to Flanders to produce a miniature portrait of the king’s would-

and his fall from power proved as swift as his rise to it. In order to form an alliance with German Protestant princes against two major continental powers, France and the Holy Roman Empire, he arranged a marriage between the King and Anne of Cleves. Holbein, the court painter, was sent to Flanders to produce a miniature portrait of the king’s would-

xxxxxIncidentally, when he was working for Cardinal Wolsey, Cromwell played a major part in the establishment of Cardinal’s College at Oxford, now known as Christ Church.

xxxxxThus the English Reformation, mainly the work of Thomas Cromwell and Thomas Cranmer, was motivated by political need, not religious pressure. Henry wanted a divorce from his wife, Catherine of Aragon, and as the pope would not grant it, he organised the divorce himself. This clearly meant a break from Rome, finalised in 1534 when he became head of the English Church. In fact, Henry himself had no time for Luther and no sympathy with the Protestant cause. Indeed, his Six Articles of 1539 enforced much of Roman Catholic doctrine. As we shall see (E6), it was left to Edward VI and then Elizabeth I (with a bloody period of the Roman Catholic Mary I in between) to establish a fully independent Anglican church.

Acknowledgements

Cromwell: portrait after Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-

H8-