GEORGES BUFFON 1707 -

xxxxxThe French naturalist Georges Buffon was appointed director of the Jardin du Roi in 1739 and ten years later embarked on a vast 44-

xxxxxThe French naturalist Georges Buffon was born in Montbard, Burgundy. His original name was Leclerc but he adopted the name Buffon from an estate his mother left him when he was about 18. He was educated at the Jesuit College in Dijon and then began to study law. In 1728, however, he gave this up and went to Angers. It was here that he first showed an interest in botany and mathematics. Obliged to leave there after taking part in a duel, he went to Nantes where he teamed up with a young Englishman. They travelled to Italy and England, but he returned to France on the death of his mother and lived on the family estate at Montbard. It was here that he acquired an interest in forestry, and it was partly due to his knowledge of timber that in 1739 he was appointed director of the Jardin du Roi (now the French botanical gardens), and of the museum within its grounds.

xxxxxThe French naturalist Georges Buffon was born in Montbard, Burgundy. His original name was Leclerc but he adopted the name Buffon from an estate his mother left him when he was about 18. He was educated at the Jesuit College in Dijon and then began to study law. In 1728, however, he gave this up and went to Angers. It was here that he first showed an interest in botany and mathematics. Obliged to leave there after taking part in a duel, he went to Nantes where he teamed up with a young Englishman. They travelled to Italy and England, but he returned to France on the death of his mother and lived on the family estate at Montbard. It was here that he acquired an interest in forestry, and it was partly due to his knowledge of timber that in 1739 he was appointed director of the Jardin du Roi (now the French botanical gardens), and of the museum within its grounds.

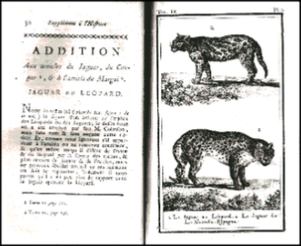

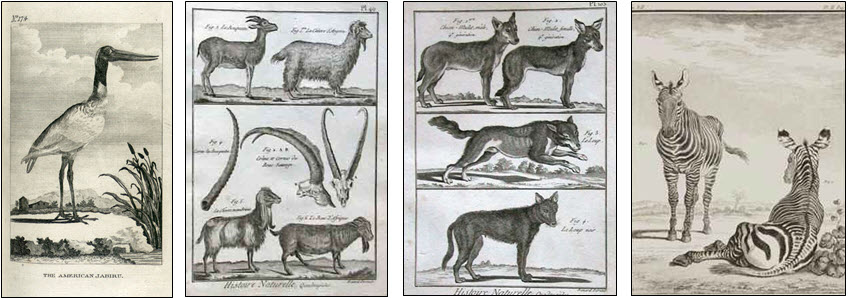

xxxxxOne of the requirements of this appointment was that he should compile a catalogue of the royal collections in natural history. This proved the start of something big. Not content with the somewhat limited scope of this assignment, he decided to cover the whole of the natural world. Thus it was that in 1749 he embarked upon a monumental task which became his life's work over the next 40 years. The result of his labours, his Natural History, eventually ran to 44 volumes and was not completed until 1804. Buffon, together with his collaborators, managed to produce 36 of them. The finished work was the first systematic attempt to bring together all the data acquired over the years in the fields of natural history, anthropology and geology. It contained hundreds of detailed descriptions and exquisite illustrations -

xxxxxOne of the requirements of this appointment was that he should compile a catalogue of the royal collections in natural history. This proved the start of something big. Not content with the somewhat limited scope of this assignment, he decided to cover the whole of the natural world. Thus it was that in 1749 he embarked upon a monumental task which became his life's work over the next 40 years. The result of his labours, his Natural History, eventually ran to 44 volumes and was not completed until 1804. Buffon, together with his collaborators, managed to produce 36 of them. The finished work was the first systematic attempt to bring together all the data acquired over the years in the fields of natural history, anthropology and geology. It contained hundreds of detailed descriptions and exquisite illustrations -

xxxxxIt was, of necessity, a collaborative work, though Buffon remained the chief author. The first 15 volumes appeared in 1767. Interesting in content and well written, they proved highly popular. The next seven volumes added to the material already published, and they were followed by nine volumes on birds (1770-

xxxxxIt was, of necessity, a collaborative work, though Buffon remained the chief author. The first 15 volumes appeared in 1767. Interesting in content and well written, they proved highly popular. The next seven volumes added to the material already published, and they were followed by nine volumes on birds (1770-

xxxxxAs one might expect, such a colossal undertaking was not likely to escape controversy, and it was not long in coming. In the opening volumes Buffon threw doubt on the whole theory of creation by suggesting -

xxxxxAs one might expect, such a colossal undertaking was not likely to escape controversy, and it was not long in coming. In the opening volumes Buffon threw doubt on the whole theory of creation by suggesting -

xxxxxA further questioning of biblical authority came in 1778 with the publication of the volume entitled The Epochs of Nature. Here, Buffon disputed the age of the Earth as calculated from bible teaching. Based on the cooling rate of iron, he argued that the Earth was not 6,000 but 74,832 years old. This vast increase was still well short of the mark, but it did open the whole question of time scale, paving the way for the introduction of geological eras.

xxxxxTo lighten his work, Buffon interspersed his detailed study of nature with personal comments on a wide range of subjects. He put forward the idea, for example, that Siberia had been the cradle of life, and he annoyed a large number of Americans -

xxxxxTo lighten his work, Buffon interspersed his detailed study of nature with personal comments on a wide range of subjects. He put forward the idea, for example, that Siberia had been the cradle of life, and he annoyed a large number of Americans -

xxxxxBut Buffon did not confine all his efforts to natural history. Always a keen mathematician, during his early years of study at Montbard, he carried out research into the calculus of probability and, in translating into French Isaac Newton's Fluxions in 1740, discussed in some detail Newton's dispute with Gottfried Leibniz over the discovery of infinitesimal calculus. And in 1748, remarkable man that he was, he also found time to assist in the development of lenses, making an improvement that was later adopted by Augustin-

xxxxxIncidentally, you may recall that some of the dinner services produced at the French porcelain factory at Sèvres were decorated with bird illustrations taken from The Natural History of Birds, one of the volumes of Buffon's vast study of nature. Below are four pages from this huge work.

Acknowledgements

Buffon: by the French painter François-

G3a-

Including:

Lazzaro

Spallanzani

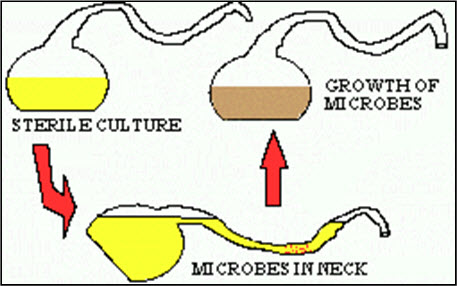

xxxxxThe theory of spontaneous generation, which had been raised by Buffon in his Natural History, was the subject of clinical research by an Italian physiologist at this time, Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729-

xxxxxThe theory of spontaneous generation raised by Buffon was the subject of research by an Italian physiologist at this time, Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729- century.

century.

xxxxxBorn in Modena in northern Italy, Spallanzani was educated in law at Bologna University, but later turned to the study of science. After working at Modena University, he became professor of physics at the University of Pavia in 1769. It was here that he carried out most of his experiments and earned his place as one of the founders of experimental biology.

xxxxxBorn in Modena in northern Italy, Spallanzani was educated in law at Bologna University, but later turned to the study of science. After working at Modena University, he became professor of physics at the University of Pavia in 1769. It was here that he carried out most of his experiments and earned his place as one of the founders of experimental biology.

xxxxxHis research was conducted over a wide field of biological interest. In 1771, for example, while examining a chick embryo, he discovered the vascular connections between veins and arteries, and monitored the effects of growth on the circulation of blood. He also made a special study of the circulation of the blood through the lungs and other organs, explained the cause of the arterial pulse, and examined the properties of the digestive juices. Other research included a detailed examination of semen in an attempt to discover what part of its make- generation, and an investigation into the ability of many lower animals to regenerate superficial parts of their bodies. He also performed some successful transplant operations -

generation, and an investigation into the ability of many lower animals to regenerate superficial parts of their bodies. He also performed some successful transplant operations -

xxxxxAxcontemporary of Georges Buffon and Carl Linnaeus was the German naturalist Peter Simon Pallas (1741-