JAMES BRINDLEY 1716 -

xxxxxIn 1761, the English engineer James Brindley, working for the Duke of Bridgewater, completed a ten mile canal from the coal mines of Worsley to the city of Manchester. The "Bridgewater Canal", England's first canal of major commercial importance, marked the start of a network of inland waterways across the country. These stimulated trade and industry, and played a vital part in the Industrial Revolution. Canal building had already produced some major waterways on the continent, particularly in France, where a number of ambitious schemes had been completed by the end of the 17th century.

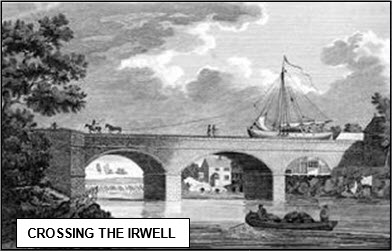

xxxxxIt was in 1759 that the Duke of Bridgewater, a pioneer in inland navigation, employed the English engineer James Brindley (illustrated) to construct a ten mile canal so that the coal he mined at his Worsley collieries could be transported to a textile factory in the city of Manchester. This "Bridgewater Canal", the first canal of major commercial importance to be built in Britain, took two years to complete (1761), and was extended to the Mersey at Liverpool -

xxxxxIt was in 1759 that the Duke of Bridgewater, a pioneer in inland navigation, employed the English engineer James Brindley (illustrated) to construct a ten mile canal so that the coal he mined at his Worsley collieries could be transported to a textile factory in the city of Manchester. This "Bridgewater Canal", the first canal of major commercial importance to be built in Britain, took two years to complete (1761), and was extended to the Mersey at Liverpool -

xxxxxBrindley was born at Tunstead, near Buxton in Derbyshire and, as a child, had little if any formal education. He began as a millwright and for a time worked in the expanding coal mining industry. In 1752, for example he designed and constructed an engine for draining coal mines at Clifton in Lancashire. After his work for the Duke of Bridgewater, however, he was employed as one of the first civil engineers, designing and, for the most part, overseeing the construction of a number of major projects. In all he built some 360 miles of canals in a network of inland waterways

xxxxxBrindley was born at Tunstead, near Buxton in Derbyshire and, as a child, had little if any formal education. He began as a millwright and for a time worked in the expanding coal mining industry. In 1752, for example he designed and constructed an engine for draining coal mines at Clifton in Lancashire. After his work for the Duke of Bridgewater, however, he was employed as one of the first civil engineers, designing and, for the most part, overseeing the construction of a number of major projects. In all he built some 360 miles of canals in a network of inland waterways which covered many parts of the country. These included the Grand Union Canal from Manchester to the potteries, the Oxford-

which covered many parts of the country. These included the Grand Union Canal from Manchester to the potteries, the Oxford-

xxxxxIncidentally, Brindley, an engineer of outstanding ability, was close to illiterate and virtually self-

xxxxxThe construction of the Bridgewater Canal marked the beginning of the canal building era in Great Britain. Over the next fifty years or so the network of waterways was considerably expanded. For example, a link was made between the Thames and the Bristol Channel via the Severn Canal, and Birmingham became the hub of a system which connected the Bristol Channel, London, the Humber and the Mersey. In Scotland, the foremost project was the building of the Caledonian Ship Canal, started by the Scottish engineer Thomas Telford in 1803 (G3c) to link up the chain of lakes which followed the line  of the Great Glen. As we shall see, this network of canals stimulated trade, (particularly in exports), brought down the cost of raw materials -

of the Great Glen. As we shall see, this network of canals stimulated trade, (particularly in exports), brought down the cost of raw materials -

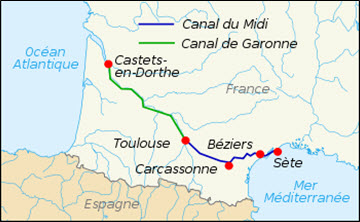

xxxxxBut this programme of canal building was by no means confined to Britain. Indeed, the French led the way in this field. By the end of the 17th century, for example, they had built canals to link the Loire with the Seine and -

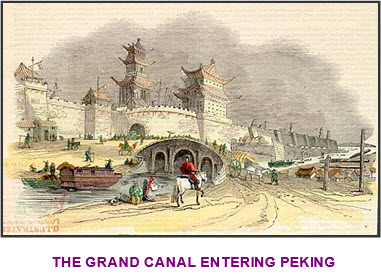

xxxxxIt must be said, of course, that canals were by no means a new phenomenon. Many were built in the earliest of times. Those in ancient Egypt and India were for irrigation purposes, but the Grand Canal in China, possibly constructed as early as the 4th century BC, was later extended to 1,000 miles, and used to transport grain from the Yangtse and Huai river valleys to the heavily populated cities further north. As we shall see, the first major ship canal in modern times, the Suez Canal, was not built until the second half of the 19th century.

Acknowledgements

Brindley: detail, by the English portrait painter Francis Parsons (active 1763/83, died 1804), 1770 – National Portrait Gallery, London. Irwell: by the English engraver and painter Robert Pollard, (1755-

G3a-

Including:

Canal Building