JAMES BOSWELL 1740 - 1795

(G2, G3a, G3b)

The Scottish biographer James Boswell came to prominence as a writer in 1768 when he published his Account of Corsica (1768), a work concerning that country's struggle for independence. He met Samuel Johnson in 1763 and this was the start of a long friendship. A great admirer of this famous man of letters, he frequently met him in London, and in 1773 spent a whole three months with him during a tour of Scotland. On every occasion he recorded Johnson's comments on a vast range of subjects, and noted verbatim his witty sayings. He published his Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides in 1785 and, six years later, followed this up with his biography, The Life of Samuel Johnson, based on a wide variety of sources and capturing the very essence of the man, warts and all. Both books were highly successful. On his death, Boswell's own papers disappeared, and were thought to have been destroyed, but in the early part of the 20th century they came to light. They were published in a series of volumes as from 1950 and threw an interesting and somewhat revealing light upon the various stages of his life - and his liking for drinking, gambling and womanizing!

xxxxxThe Scottish biographer and diarist James Boswell first met Samuel Johnson in May 1763 at the age of 22. This meeting proved the start of a lasting friendship, despite their differences in age, intelligence and social standing. A great admirer of Johnson and his works, Boswell kept a detailed record of their meetings, including an almost verbatim account of their conversations. But it was the three month visit they made to Scotland in 1773 that gave him a prolonged and unique opportunity to study the literary giant at close quarters. Indeed, the work he wrote on their return, Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, published in 1785, provided much material for his more famous work, The Life of Samuel Johnson, produced six years later.

xxxxxThe Scottish biographer and diarist James Boswell first met Samuel Johnson in May 1763 at the age of 22. This meeting proved the start of a lasting friendship, despite their differences in age, intelligence and social standing. A great admirer of Johnson and his works, Boswell kept a detailed record of their meetings, including an almost verbatim account of their conversations. But it was the three month visit they made to Scotland in 1773 that gave him a prolonged and unique opportunity to study the literary giant at close quarters. Indeed, the work he wrote on their return, Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, published in 1785, provided much material for his more famous work, The Life of Samuel Johnson, produced six years later.

xxxxxApart from capturing the very essence of the man himself - warts and all - both works provided a rich store of Johnson’s witty and pithy comments on a whole range of subjects, revealing his ability to sum up in a sentence “the great rules of life”. The biography, however, was much more personal and covered Johnson's entire life. In addition to his own personal notes and anecdotes, Boswell used a wide variety of sources, including Johnson's own private papers, and letters and reminiscences from many of his friends and acquaintances. Not surprisingly, this work has come to be regarded as one of the great books of English literature. Later, Boswell was to remark that his subject was seen “more completely than any man who has ever yet lived”, and that his type of biography “is the most perfect that can be conceived”. They were no idle boasts, for his work did greatly influence the art of writing biography for centuries to come.

xxxxxApart from capturing the very essence of the man himself - warts and all - both works provided a rich store of Johnson’s witty and pithy comments on a whole range of subjects, revealing his ability to sum up in a sentence “the great rules of life”. The biography, however, was much more personal and covered Johnson's entire life. In addition to his own personal notes and anecdotes, Boswell used a wide variety of sources, including Johnson's own private papers, and letters and reminiscences from many of his friends and acquaintances. Not surprisingly, this work has come to be regarded as one of the great books of English literature. Later, Boswell was to remark that his subject was seen “more completely than any man who has ever yet lived”, and that his type of biography “is the most perfect that can be conceived”. They were no idle boasts, for his work did greatly influence the art of writing biography for centuries to come.

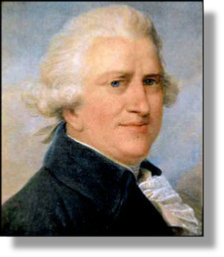

xxxxxBoswell was born in Edinburgh, the son of Alexander Boswell, a Scottish lawyer who later became a judge with the judicial title of Lord Auchinleck. He studied law at Edinburgh University and then went to Glasgow University, where he attended lectures given by the economist Adam Smith. He practised law, but his interest lay in politics and literature, and from 1760 he spent much of his time in London, enjoying the refined and the not-so-refined pleasures of that city's life. It was soon after meeting Johnson that he visited a number of countries on the continent and, so it happened, greatly advanced his literary career. After meeting the French philosophers Jean Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire, he met up with the Corsican chieftain general Pasquale Paoli (here illustrated), then leading his country in an independence struggle against the Genoese. On his return, his Account of Corsica, published in 1768, in which he sought support for the nationalist cause, gained him an international reputation. He married his first cousin, Margaret Montgomerie, in 1769 and three years later renewed his acquaintance with Johnson. In 1773 he became a member of his prestigious Literary Club, just a few months prior to their visit to Scotland.

xxxxxBoswell was born in Edinburgh, the son of Alexander Boswell, a Scottish lawyer who later became a judge with the judicial title of Lord Auchinleck. He studied law at Edinburgh University and then went to Glasgow University, where he attended lectures given by the economist Adam Smith. He practised law, but his interest lay in politics and literature, and from 1760 he spent much of his time in London, enjoying the refined and the not-so-refined pleasures of that city's life. It was soon after meeting Johnson that he visited a number of countries on the continent and, so it happened, greatly advanced his literary career. After meeting the French philosophers Jean Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire, he met up with the Corsican chieftain general Pasquale Paoli (here illustrated), then leading his country in an independence struggle against the Genoese. On his return, his Account of Corsica, published in 1768, in which he sought support for the nationalist cause, gained him an international reputation. He married his first cousin, Margaret Montgomerie, in 1769 and three years later renewed his acquaintance with Johnson. In 1773 he became a member of his prestigious Literary Club, just a few months prior to their visit to Scotland.

xxxxxFor the next few years, Boswell worked in Scotland - one time serving as an examiner for the Faculty of Advocates - but he did not succeed in obtaining a seat in Parliament, and became disillusioned, regarding himself as a failure. In 1782 he retired with his wife and family to his estate at Auchinleck in East Ayrshire, but in 1785, a year after the death of Johnson, he returned to London to see through the publication of his The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, with Samuel Johnson. The following year he qualified as a barrister, but spent most of his time writing up his famous biography, published in 1791. Both these works were highly successful, but Boswell himself did not come out of them well. Many critics saw him as Johnson's  lap dog, a man of little character, fed by his master. Earlier he had been described as a “Scotch cur at Johnson's heels”. It is little wonder that his final years were unhappy ones and that he should again take to drink. He died in 1795 while working on the third edition of his biography.

lap dog, a man of little character, fed by his master. Earlier he had been described as a “Scotch cur at Johnson's heels”. It is little wonder that his final years were unhappy ones and that he should again take to drink. He died in 1795 while working on the third edition of his biography.

xxxxxIt took many years before Boswell the man was revealed. His personal papers, including his journals, went missing for many years and were presumed destroyed. They suddenly came to light, however, in the 1920s and 1930s, the bulk of them found tied up in bundles or stored in old boxes at Malahide Castle, near Dublin, the home of one of Boswell's descendants, Lord Talbot de Malhides. They were eventually obtained by Yale University via an American antiquarian, and published in a series of volumes, beginning in 1950. His journals, started in 1769 and, written in a lively style, throw a fascinating light upon the various stages of his life - his extensive and significant tour of the continent in the 1760s, for example; his time in London in the circle of Johnson's brilliant friends; his work as a lawyer, and the time spent with his family on his country estate at Auckinleck. And they touch, too, upon that other side of his life - his gambling, drinking and womanizing. The character which emerges from these papers is far from the one dismissed out of hand by his critics when he was alive!

xxxxxIncidentally, in his biography, Boswell states that the name “bluestockings” - applied to women of the 18th century who met to discuss intellectual matters - was coined when a certain Mrs Elizabeth Vesey, the member of a group of learned ladies led by Mrs Elizabeth Montagu, invited the erudite Benjamin Stillingfleet (1702-1771) to one of their gatherings. He declined, saying that he did not have the right dress for such an occasion, whereupon she told him to come in the stockings he was wearing - an ordinary pair in blue worsted. This he did, and from then onwards the group took on the name of Bluestocking (Bas Bleu in French), and its members became known as “Bluestockings”. Fanny Burney, a close friend of Dr. Johnson, was one of the best known of the Bluestockings. From the 19th century, however, the term came to be used as a derisive term to describe intellectual women. ……

xxxxxIncidentally, in his biography, Boswell states that the name “bluestockings” - applied to women of the 18th century who met to discuss intellectual matters - was coined when a certain Mrs Elizabeth Vesey, the member of a group of learned ladies led by Mrs Elizabeth Montagu, invited the erudite Benjamin Stillingfleet (1702-1771) to one of their gatherings. He declined, saying that he did not have the right dress for such an occasion, whereupon she told him to come in the stockings he was wearing - an ordinary pair in blue worsted. This he did, and from then onwards the group took on the name of Bluestocking (Bas Bleu in French), and its members became known as “Bluestockings”. Fanny Burney, a close friend of Dr. Johnson, was one of the best known of the Bluestockings. From the 19th century, however, the term came to be used as a derisive term to describe intellectual women. ……

xxxxx…… MrsxElizabeth Montagu (1718-1800) was one of the leading ladies of the Blue Stocking Society. A wealthy patron of the arts and a literary critic, she had become the foremost London hostess by 1760. Her “evening entertainments”, held at her home in Hill Street - during which strong drink and card playing were forbidden! - were always well attended. Among her distinguished circle of friends were Samuel Johnson, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Edmund Burke and Horace Walpole. Authors also included Hannah More and Fanny Burney. She herself wrote An Essay on the Writings and Genius of Shakespeare, published in 1769.

Including:

“Blue Stockings”

and Hester Thrale

Acknowledgements

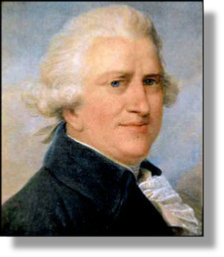

Boswell: detail, by the English portrait painter Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), 1785 – National Portrait Gallery, London. Conversation: after the English painter Eyre Crowe (1824-1910) – private collection. Paoli: by the English portrait painter Richard Cosway (1742-1821), 1798 – private collection. Thrale: detail, by the English portrait painter Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), 1781 – Beaverbrook Art Collection, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada.

G3a-1760-1783-G3a-1760-1783-G3a-1760-1783-G3a-1760-1783-G3a-1760-1783-G3a

xxxxxAnother of Johnson's close friends, Hester Thrale (1741-1821), also wrote about him. Married to a wealthy brewer, she met Johnson in 1765, and he enjoyed her hospitality and friendship over the next 16 years. He stayed very often at her estate at Streatham - becoming accepted as one of the family - and as a society hostess she held frequent dinner parties for Johnson and his large circle of distinguished friends. After his death she produced Anecdotes of the late Samuel Johnson in 1786 and, two years later, Letters to and from the late Samuel Johnson. These works were not as full or as accurate as Boswell’s biography proved to be, but they did emphasize the warmer and more sympathetic side of Johnson's nature.

xxxxxAnother of Johnson’s very close friends, Hester Thrale (1741-1821), also produced biographical details of the great man. The wife of a wealthy brewer, she first met Johnson in 1765, and for the next 16 years he spent a great deal of his time at the family’s estate in Streatham, enjoying the comforts and the security of a happy home life. So close did their friendship become, that he went on trips with them to Wales and France. A vivacious and attractive hostess, it was during this time that she gave frequent and celebrated dinner parties for Johnson and his friends.

xxxxxAnother of Johnson’s very close friends, Hester Thrale (1741-1821), also produced biographical details of the great man. The wife of a wealthy brewer, she first met Johnson in 1765, and for the next 16 years he spent a great deal of his time at the family’s estate in Streatham, enjoying the comforts and the security of a happy home life. So close did their friendship become, that he went on trips with them to Wales and France. A vivacious and attractive hostess, it was during this time that she gave frequent and celebrated dinner parties for Johnson and his friends.

xxxxxBut in 1784 the friendship became to an abrupt end. Mrs Thrale’s husband died in 1781, and three years later she married her daughter’s music teacher, an Italian singer and composer named Gabriel Piozzi. Johnson strongly disapproved of the marriage - as did others - and this caused a break down in their friendship, an estrangement that seriously saddened the last months of Johnson’s life. Following his death later that year, she put together her Anecdotes of  the late Samuel Johnson in 1786. As a piece of biography, it was not as accurate or as detailed as Boswell’s, and it only covered the last twenty years of Johnson’s life, but it did concentrate more upon the warmer and sympathetic side of Johnson’s nature. Intentionally or not, this work was seen as being in direct competition with Boswell’s own work in the making, and matters were made worse in 1788 when she published a two-volume edition of Letters to and from the late Samuel Johnson. She never fully regained her position in London society, but she made a new circle of friends, and left a wealth of interesting correspondence.

the late Samuel Johnson in 1786. As a piece of biography, it was not as accurate or as detailed as Boswell’s, and it only covered the last twenty years of Johnson’s life, but it did concentrate more upon the warmer and sympathetic side of Johnson’s nature. Intentionally or not, this work was seen as being in direct competition with Boswell’s own work in the making, and matters were made worse in 1788 when she published a two-volume edition of Letters to and from the late Samuel Johnson. She never fully regained her position in London society, but she made a new circle of friends, and left a wealth of interesting correspondence.

xxxxxThe Scottish biographer and diarist James Boswell first met Samuel Johnson in May 1763 at the age of 22. This meeting proved the start of a lasting friendship, despite their differences in age, intelligence and social standing. A great admirer of Johnson and his works, Boswell kept a detailed record of their meetings, including an almost verbatim account of their conversations. But it was the three month visit they made to Scotland in 1773 that gave him a prolonged and unique opportunity to study the literary giant at close quarters. Indeed, the work he wrote on their return, Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, published in 1785, provided much material for his more famous work, The Life of Samuel Johnson, produced six years later.

xxxxxThe Scottish biographer and diarist James Boswell first met Samuel Johnson in May 1763 at the age of 22. This meeting proved the start of a lasting friendship, despite their differences in age, intelligence and social standing. A great admirer of Johnson and his works, Boswell kept a detailed record of their meetings, including an almost verbatim account of their conversations. But it was the three month visit they made to Scotland in 1773 that gave him a prolonged and unique opportunity to study the literary giant at close quarters. Indeed, the work he wrote on their return, Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, published in 1785, provided much material for his more famous work, The Life of Samuel Johnson, produced six years later. xxxxxApart from capturing the very essence of the man himself -

xxxxxApart from capturing the very essence of the man himself - xxxxxBoswell was born in Edinburgh, the son of Alexander Boswell, a Scottish lawyer who later became a judge with the judicial title of Lord Auchinleck. He studied law at Edinburgh University and then went to Glasgow University, where he attended lectures given by the economist Adam Smith. He practised law, but his interest lay in politics and literature, and from 1760 he spent much of his time in London, enjoying the refined and the not-

xxxxxBoswell was born in Edinburgh, the son of Alexander Boswell, a Scottish lawyer who later became a judge with the judicial title of Lord Auchinleck. He studied law at Edinburgh University and then went to Glasgow University, where he attended lectures given by the economist Adam Smith. He practised law, but his interest lay in politics and literature, and from 1760 he spent much of his time in London, enjoying the refined and the not-

lap dog, a man of little character, fed by his master. Earlier he had been described as a “Scotch cur at Johnson's heels”. It is little wonder that his final years were unhappy ones and that he should again take to drink. He died in 1795 while working on the third edition of his biography.

lap dog, a man of little character, fed by his master. Earlier he had been described as a “Scotch cur at Johnson's heels”. It is little wonder that his final years were unhappy ones and that he should again take to drink. He died in 1795 while working on the third edition of his biography.  xxxxxIncidentally, in his biography, Boswell states that the name “bluestockings” -

xxxxxIncidentally, in his biography, Boswell states that the name “bluestockings” -

xxxxxAnother of Johnson’s very close friends, Hester Thrale (1741-

xxxxxAnother of Johnson’s very close friends, Hester Thrale (1741- the late Samuel Johnson in 1786. As a piece of biography, it was not as accurate or as detailed as Boswell’s

the late Samuel Johnson in 1786. As a piece of biography, it was not as accurate or as detailed as Boswell’s