WILLIAM BLACKSTONE 1723 -

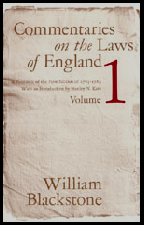

xxxxxThe English jurist William Blackstone completed the publication of his Commentaries on the Laws of England in 1769. Based mainly on his lectures at Oxford University, this work was the first comprehensive treatment of the subject, and it was written in simple, understandable language. It was an immediate success and, despite attracting some criticism, especially from the philosopher Jeremy Bentham, it formed the basis of university law courses in both Britain and North America for over a century. He was the first professor of English law at Oxford University, a member of parliament for nine years, and was knighted in 1770. He spent the last years of his life working for prison reform.

xxxxxThe English jurist William Blackstone, author of the influential Commentaries on the Laws of England, was born in London. After attending Charterhouse and Pembroke College, Oxford, he read law at the Middle Temple, and in 1746 set up a law practice in Westminster. As a barrister, it would appear, he was not particularly successful. Seven years later he returned to Oxford where he introduced courses in English law. By 1750 he had produced a number of legal treatises, but it was the publication of his lectures in 1756, under the title An Analysis of the Laws of England, that gained him a reputation as a talented legal scholar. In 1758 he was appointed the first professor of English law at Oxford University, and this led to various government appointments -

xxxxxThe English jurist William Blackstone, author of the influential Commentaries on the Laws of England, was born in London. After attending Charterhouse and Pembroke College, Oxford, he read law at the Middle Temple, and in 1746 set up a law practice in Westminster. As a barrister, it would appear, he was not particularly successful. Seven years later he returned to Oxford where he introduced courses in English law. By 1750 he had produced a number of legal treatises, but it was the publication of his lectures in 1756, under the title An Analysis of the Laws of England, that gained him a reputation as a talented legal scholar. In 1758 he was appointed the first professor of English law at Oxford University, and this led to various government appointments -

xxxxxHe began publishing his Commentaries in 1765 and by 1769 had produced four volumes. Like his earlier work, these were mainly based upon his Oxford lectures, though he also gained some assistance from a 17th century treatise entitled The History and Analysis of the Common Law of England -

xxxxxHe began publishing his Commentaries in 1765 and by 1769 had produced four volumes. Like his earlier work, these were mainly based upon his Oxford lectures, though he also gained some assistance from a 17th century treatise entitled The History and Analysis of the Common Law of England -

xxxxxIn 1770 Blackstone was appointed a justice of the Court of Common Pleas, and he was knighted in that year. During his nine years as a member of parliament (1761-

Acknowledgements

Blackstone: detail, c1755, artist unknown – National Portrait Gallery, London. Howard: by the American portrait painter Mather Brown (1761-

G3a-

Including:

John

Howard

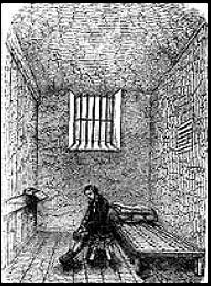

xxxxxAnother Londoner interested in prison reform at this time was the philanthropist John Howard (1726-

xxxxxAnother Londoner who was much involved in prison reform at this time was the philanthropist John Howard (1726-

xxxxxAnother Londoner who was much involved in prison reform at this time was the philanthropist John Howard (1726-

xxxxxIn 1775 he made a tour of prisons in other parts of the country, and also visited establishments on the continent. Two years later he published his findings in The State of the Prisons in England and Wales, together with an account of Foreign Prisons. These reports made for depressing reading. Then in  1779, anxious to assist in the rehabilitation of prisoners, he played a part in persuading parliament to authorise the provision of two special units where, by supervised labour and religious instruction, prisoners could be encouraged to change their ways. But despite these good intentions, this act, like those of 1774, was never strictly enforced. However, his work to improve prison conditions was continued, and is conducted today by the Howard League for Penal Reform.

1779, anxious to assist in the rehabilitation of prisoners, he played a part in persuading parliament to authorise the provision of two special units where, by supervised labour and religious instruction, prisoners could be encouraged to change their ways. But despite these good intentions, this act, like those of 1774, was never strictly enforced. However, his work to improve prison conditions was continued, and is conducted today by the Howard League for Penal Reform.

xxxxxHe spent the last years of his life travelling on the continent, attempting to find the means of limiting the spread of contagious diseases. In 1786 he deliberately boarded a ship full of sickness and travelled from Smyrna to Venice to gain firsthand knowledge of lazarettos -

xxxxxAs we shall see, Howard’s work towards prison reform was ably continued by the English Quaker Elizabeth Fry. After visiting Newgate prison, London, in 1813 (G3c), she devoted most of her life to fighting for better conditions in penal institutions, particularly with regard to the treatment of women prisoners.