THE BATTLES OF HAKATA BAY 1274 AND 1281 (E1)

Including:

Chao Meng-

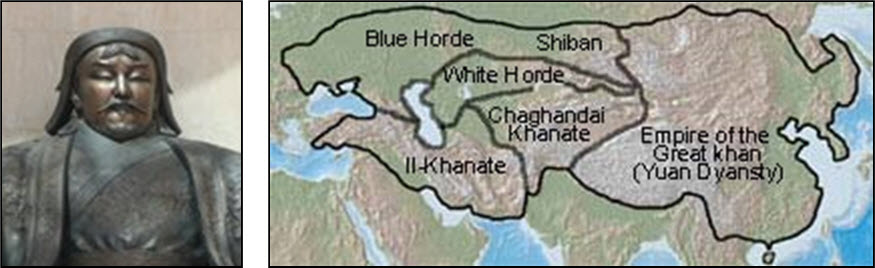

xxxxxAs we have seen, Kublai Khan was proclaimed the Mongol Emperor in 1260 (H3) and, continuing his conquest of China, had gained control of this country within 20 years. Virtually abandoning his other territories, he then assumed the title Emperor of China and set out to expand his new domain. He had little success. He had already attempted to invade Japan in 1274 and been defeated in Hakata Bay. In 1281 a second attempt also ended in disaster when a storm forced his fleet to turn back. Nor was he any more successful on land. His expedition to Java in 1293 ended in failure, and, following a series of defeats, he had to withdraw his forces from Burma and Vietnam. In China, he maintained much of the ancient civilisation and this, together with religious toleration, gave his empire a good name, further enhanced by the writings of the Venetian traveller Marco Polo. But the Mongol Empire itself contained the seeds of its own destruction. It was making no lasting roots, whether it ruled by oppression or became submerged by the civilisation it overran. As we shall see, in 1294 Kublai Khan’s successor Temur managed to keep the empire intact, but the rot had begun to set in.

xxxxxAs we have seen, Kublai, grandson of Genghis Khan, had had himself proclaimed the new Khan in 1260 (H3). In 1267 he resumed his conquest of China and in 1271, having conquered most of the northern area, he established his own dynasty of Ta Yuan (Great Origin) and moved his capital from Karakorum to Beijing. It was not until 1279, however, that the Sung dynasty in the south had been fully destroyed and Chinese unity had been accomplished.

xxxxxHe now relinquished his claims to all other parts of the Mongolian Empire. Assuming the title of Emperor of China and establishing the new Mongol dynasty of Yuan -

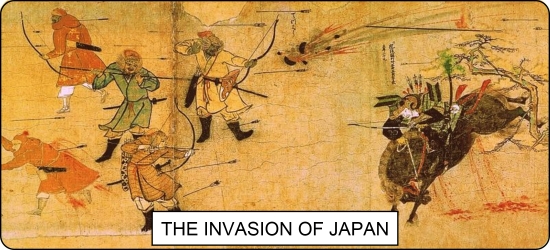

xxxxxIn 1274 he sent a fleet to invade Japan but it was defeated and turned back in Hakata Bay. While returning to the Korean mainland a violent storm arose and the fleet was almost totally destroyed. Then a second attempt at invasion, made in 1281, also ended in disaster. It reached Hakata Bay, but was then driven back by a typhoon, or, as the Japanese were pleased to regard it, a kamikaze or divine wind!

xxxxxIn his colonial wars to the south he fared little better. Indeed, during these encroachments the Mongol armies suffered some serious defeats. They managed at one time to overrun parts of Vietnam (1284 and 1287) and Burma (1287), but the expedition to Java ended in failure (1293), and the Empire gained little from these military excursions. His successor put an end to them.

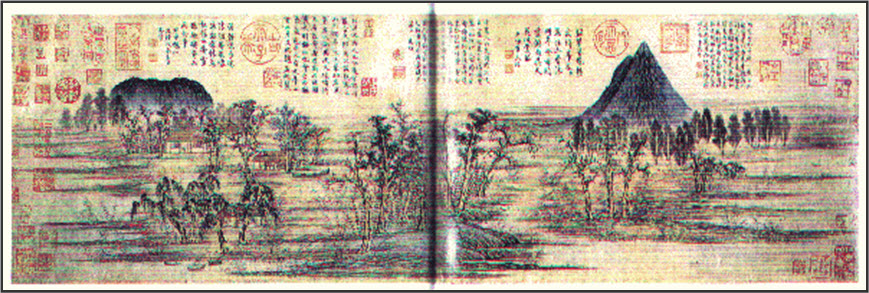

xxxxxAt home, under Kublai Khan’s rule, the court of Cambaluc gained a reputation for its cultivation of literature and the arts. There was also a great deal of religious toleration. Though the Emperor himself was a devout Buddhist and made Buddhism the state religion, Taoism and Confucianism were accepted, and the Muslim faith and Christianity were tolerated. Thanks mainly to the writings of the Venetian traveller Marco Polo, Kublai Khan became known all over Asia and Europe, as did the impressive nature of the empire over which he ruled.

xxxxxAt home, under Kublai Khan’s rule, the court of Cambaluc gained a reputation for its cultivation of literature and the arts. There was also a great deal of religious toleration. Though the Emperor himself was a devout Buddhist and made Buddhism the state religion, Taoism and Confucianism were accepted, and the Muslim faith and Christianity were tolerated. Thanks mainly to the writings of the Venetian traveller Marco Polo, Kublai Khan became known all over Asia and Europe, as did the impressive nature of the empire over which he ruled.

xxxxxAlthough accounts about China at this time were generally favourable, in the Mongol Empire as a whole a deep split continued over those members who wished to maintain the methods of conquest followed by Genghis Khan -

xxxxxBut, as we shall see, both approaches contained the seeds of destruction as far as the Mongol Empire was concerned. The first did not achieve the building of a lasting empire. Once the horde moved on, the rule of the invader came to an end. In the second, the Mongolians - enormous and, in many ways, fragile empire. As we shall see, with Kublai Khan’s death in

enormous and, in many ways, fragile empire. As we shall see, with Kublai Khan’s death in

xxxxxIncidentally, as noted earlier, the nineteenth century English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote a poem entitled Kubla Khan. He claimed that, after reading about the Mongol leader, he fell asleep and wrote the entire poem in his sleep. It’s a beautiful piece of verse about Kublai Khan’s summer palace at Shang-

xxxxxAmong the many writers and artists who attended Kublai Khan’s court, was the outstanding painter and calligrapher Chao Meng-

E1-

Acknowledgements

Kublai Khan: detail of statue outside Parliament House, Sukhbaatar Square, Ulan Bator, Mongolia. Map (Mongol Empire): licensed under Creative Commons -