Including:

Robert Bruce

(continued)

and

John Barbour

THE BATTLE OF BANNOCKBURN 1314 (E2)

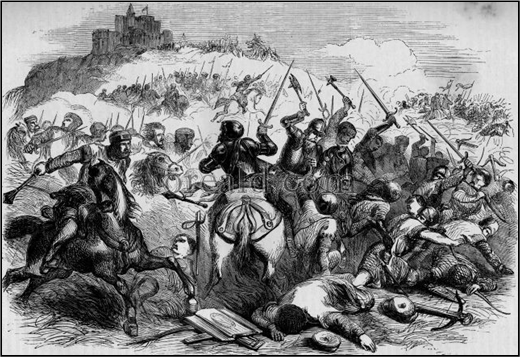

xxxxxAs we have seen, following the death of William Wallace, Robert Bruce was crowned king of Scotland in March 1306 (E1). He was soon defeated in battle, but he managed to escape and returned to the fight in 1307, waging a constant guerrilla war against the forces of the new King, Edward II. Then in 1314 he won an outstanding victory at the Battle of Bannockburn. Despite being heavily outnumbered, his force of pikemen, bowmen and cavalry took up a good defensive position beside an area of marshland. Two cavalry assaults by the English failed, the horses foundering in the muddy terrain or proving unable to penetrate the wooden stakes and deep pits which made up the Scots’ line of defence. Then when a force of Scottish camp-

xxxxxAs we have seen, in 1306 (E1), following the capture and execution of the Scottish resistance leader William Wallace, Robert Bruce, a loyal subject of the English king, was selected as one of the four regents to govern the kingdom in the name of John Balliol. On the 10th February 1306, however, he got into a quarrel with John Comyn, a cousin of John Balliol and a possible contender for the throne. During their meeting, which took place in Greyfriars Church at Dumfries, Comyn was stabbed to death by Bruce. The motive for the killing was not difficult to find because Bruce then made straight for Scone Abbey and was crowned king of Scotland the following month.

xxxxxAs we have seen, in 1306 (E1), following the capture and execution of the Scottish resistance leader William Wallace, Robert Bruce, a loyal subject of the English king, was selected as one of the four regents to govern the kingdom in the name of John Balliol. On the 10th February 1306, however, he got into a quarrel with John Comyn, a cousin of John Balliol and a possible contender for the throne. During their meeting, which took place in Greyfriars Church at Dumfries, Comyn was stabbed to death by Bruce. The motive for the killing was not difficult to find because Bruce then made straight for Scone Abbey and was crowned king of Scotland the following month.

xxxxxEdward I, you may remember, acted at once. He deposed Bruce and ordered his forces in Scotland to hunt the traitor down. They defeated Bruce in two battles in that year and captured many of his supporters and relatives, including his wife and three of his brothers. Bruce managed to escape, but was forced to flee the mainland, taking refuge on the little island of Rathlin off the coast of Antrim in northern Ireland.

xxxxxIn February 1307 Bruce returned to Ayrshire, hoping to drum up enough support to oppose and beat off the inevitable English challenge. But the challenge never came. Edward I mustered an army and travelled north to re-

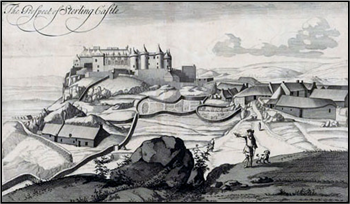

xxxxxFor the next few years Bruce waged a constant guerrilla war against the English garrisons in Scotland and those of his countrymen who continued to support the king of England. He won a number of skirmishes, took over most of the English strongholds, and even led attacks into northern England. Edward II was reluctant to follow in his father's footsteps, but eventually, when only Berwick and Stirling were left in English hands, he decided that some action was needed. In the spring of 1314 he led a large army into Scotland with the immediate aim of relieving the besieged castle at Stirling (illustrated). Bruce was waiting for him.

xxxxxThe two armies met just south of Stirling in June of that year. The English army, some 18,000 strong, consisted of a large cavalry force of about 2,000 and the best archers in Europe, and it outnumbered the Scots by something like three to one. The Scottish force was made up of pikemen, bowmen and just a few cavalry, but, under Bruce's guidance, it was drawn up in an area between a small stream, the Bannockburn, and the River Forth in a narrow opening bordered by dense woods or marshland. In addition, the forward area was protected with a mass of wooden stakes and deep pits (or pottées). These frontal defensive measures were crude, but they were to prove highly effective.

xxxxxEdward, anxious to reach a quick conclusion, made only a brief use of his archers before sending in his cavalry, but two waves of attack by the English knights ended in total failure. The horses floundered in the mud and fell into the pits. Then a large number of Scottish camp-

xxxxxDespite this disastrous defeat, Edward refused to grant independence to Scotland and the war dragged on for fourteen years. In 1326, however, a Scottish Parliament was established, securing some measure of independence, and then, as we shall see, in 1328 (E3) Roger Mortimer, acting on behalf of the young Edward III, persuaded him to sign the Treaty of Northampton by which Scotland became an independent kingdom, and Robert Bruce became its king

xxxxxIncidentally, just before he died at Carlisle in 1307, Edward I -

xxxxx...... And speaking of caskets, Robert Bruce died in 1329 just a year after Scotland gained its independence. He was buried at Dunfermline Abbey but, following his wishes, his heart was removed, placed in a silver casket, and taken to the Holy Land by his friend Sir James Douglas. (Bruce had vowed to take part in a crusade but never fulfilled his vow). It is known that Douglas was killed on the way, fighting the Moors in Spain, but much doubt has been cast on the story that the casket was then recovered, brought back to Melrose Abbey and buried at the high altar. However, today a carved stone marks the place where the casket is said to be buried. ……

xxxxx...... And speaking of caskets, Robert Bruce died in 1329 just a year after Scotland gained its independence. He was buried at Dunfermline Abbey but, following his wishes, his heart was removed, placed in a silver casket, and taken to the Holy Land by his friend Sir James Douglas. (Bruce had vowed to take part in a crusade but never fulfilled his vow). It is known that Douglas was killed on the way, fighting the Moors in Spain, but much doubt has been cast on the story that the casket was then recovered, brought back to Melrose Abbey and buried at the high altar. However, today a carved stone marks the place where the casket is said to be buried. ……

xxxxx…… During the English retreat from the battlefield Edward was very nearly captured. It is said that, as a thanksgiving for his escape, he founded Oriel College in Oxford in 1326. ……

xxxxx…… The year after Bannockburn, 1315, saw the start of a three-

xxxxxThe Scottish poet John Barbour (c1325-

xxxxxThe Scottish poet John Barbour (c1325-

Acknowledgements

Robert Bruce: detail of statue at Stirling Castle, Scotland. Stirling Castle: drawn by the Dutch/German military engineer John Slezer (c1650-

E2-