GEORGIUS AGRICOLA 1494 -

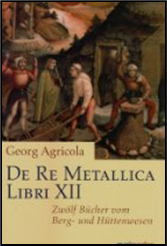

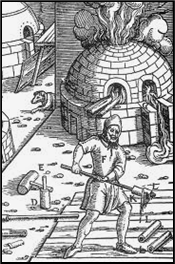

xxxxxThe German physician and scientist Georgius Agricola published his On Natural Fossils in 1546, the first treatise on mineralogy. In it, he classified "fossils" (any object dug out of the ground) and gave details of each item, some of which were previously unknown. His interest in mineralogy began in 1527 when he worked as a physician in the mining town of Joachimsthal. He wrote no less than seven books on the subject, including his masterpiece On Metals, a valuable, illustrated textbook which assisted mining engineers and surveyors over the next two centuries. A cultured man, he was a life-

xxxxxOn Natural Fossils, the work of the German physician and scientist Georgius Agricola in 1546, was the first textbook on mineralogy and made an outstanding contribution to this subject. It not only classified various kinds of rocks, organic remains and minerals ("fossil" at that time meant any object dug out of the ground), but it also provided detailed information about each mineral recorded, some for the first time.

xxxxxOn Natural Fossils, the work of the German physician and scientist Georgius Agricola in 1546, was the first textbook on mineralogy and made an outstanding contribution to this subject. It not only classified various kinds of rocks, organic remains and minerals ("fossil" at that time meant any object dug out of the ground), but it also provided detailed information about each mineral recorded, some for the first time.

xxxxxBorn Georg Bauer (Agricola was the Latinized form of his name), he was educated in the classics and taught Latin and Greek before studying medicine at the universities of Bologna, Padua and Venice. In 1527 he began practising in Joachimsthal, a mining town in the former state of Czechoslovakia, where he became fascinated by all aspects of the metallurgy industry. Over the next twenty-

xxxxxBorn Georg Bauer (Agricola was the Latinized form of his name), he was educated in the classics and taught Latin and Greek before studying medicine at the universities of Bologna, Padua and Venice. In 1527 he began practising in Joachimsthal, a mining town in the former state of Czechoslovakia, where he became fascinated by all aspects of the metallurgy industry. Over the next twenty-

xxxxxA cultured man, he met the Dutch humanist Erasmus while in Italy and they became life-

xxxxxIncidentally, his masterpiece, De re metallica, although published in 1556, was not translated into English until 1912. The translation was the work of the mining engineer Herbert Hoover and his wife. Hoover -

Including:

Leonhard

Fuchs

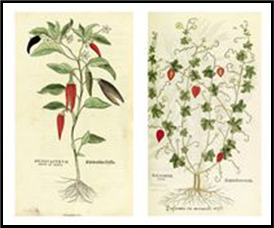

xxxxxAnother German who brought order out of chaos -

xxxxxAnother German who brought order out of chaos -

xxxxxFuchs studied medicine and was later appointed professor in this subject at Tubingen. He originally started compiling his botanical work because of his interest in the medical properties of plants. In recognition of his contribution to the study of botany, the flowering plant Fuschia was named after him.

xxxxxAnother outstanding German at this time was the botanist Leonhard Fuchs (1501-

Acknowledgements

Agricola: date and artist unknown. Woodut from Agricola’s De re metallica, 16th century – National Coal Mining Museum of England, Overton, Wakefield.

H8-