The Scotsman Robert Adam was an outstanding British architect, best known for the elegance of his interior designs. He started work in Scotland with his brother John, continuing the Palladian style taught them by their father. He then spent over three years on the continent, studying ancient Roman architecture, and returned to establish a flourishing practice in London, assisted by his brother James. He was made joint architect to the king in 1762 and this increased their commissions. Most of their work was concerned with the remodelling of stately homes along neo-classical lines, and the design of all interior decor, furnishings and fittings in what came to be known as the “Adam Style”. This was remarkable for its classical simplicity, the use of ancient Roman and Greek motifs in delicate stucco work, and its soft pastel shades on walls and ceilings. Among the homes remodelled in this way were Osterley Park and Syon House near London, Harewood House in Yorkshire, Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire, and Saltram House near Plymouth in Devon. The brothers also embarked on the “Adelphi Scheme”, developing the stretch of marshland which lay between the Strand and the River Thames in London. An ambitious project which included terraces of elegant houses and a dockland area, it almost brought financial ruin. The Adam style spread far and wide, assisted by two publications, the Ruins of the Palace of Diocletian, produced by Robert in 1764, and Works in Architecture, written together with his brother James some ten years later. The style was adopted in America under the title the “Federal Style”, and introduced into the court of Catherine the Great of Russia. In his final years Adam produced some fine civic buildings in Edinburgh, and built a number of romantic, neo-Gothic castles in Scotland, such as Culzean Castle in Ayrshire.

ROBERT ADAM 1728 - 1792 (G2, G3a, G3b)

Acknowledgements

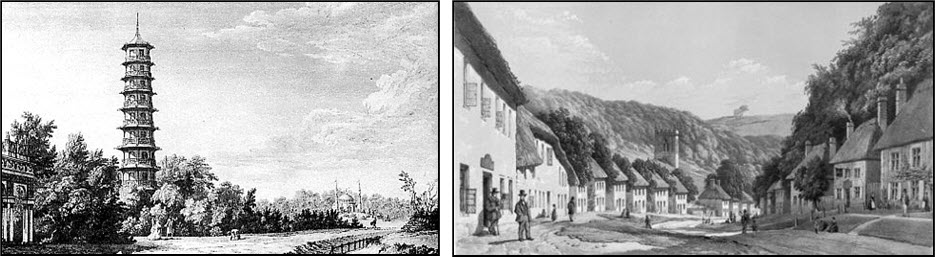

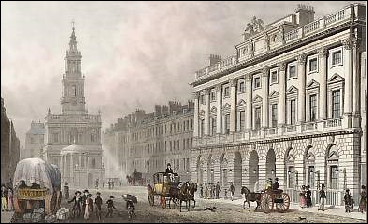

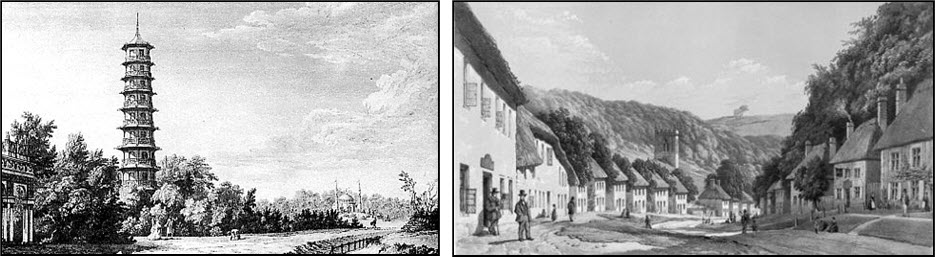

Adam: detail, attributed to the Scottish portrait painter George Willison (1741-1797), 1770/5 – National Portrait Gallery, London. Interiors: dates and photographers unknown. Adelphi: engraving, 19th century, artist unknown – private collection. Culzean: steel engraving, drawn by the English artist William Daniell (1769-1837), and engraved by the Scottish artist John Cochrane (active 1821-1865). Classicism: by the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) – contained in his Varie Veduta de Roma Antica e Moderna of 1745. Three Graces: by the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova (1757-1822), 1814/17 – Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Chambers: detail, by the English painter Francis Cotes (1726-1770), 1764 – National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh. Somerset House: steel engraving, hand coloured, drawn by the English artist Thomas Hosmer Shepherd (1792-1864) and engraved by the English printmaker William Tombleson (1795-c1846), 1829. Pagoda: date and artist unknown – Museum of London. Milton Abbas: engraving, c1851, artist unknown – Drawing and Archives Collection, Royal Institute of British Architects, London.

G3a-1760-1783-G3a-1760-1783-G3a-1760-1783-G3a-1760-1783-G3a-1760-1783-G3a

xxxxxThe Scotsman Robert Adam was one of the most outstanding British architects and designers of the late 18th century. He was born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, but soon after his birth his family moved to Edinburgh. He attended the High School there and then, like his three brothers, was trained by his father William Adam, a leading Scottish architect of his day. When his father died in 1748, he worked with his older brother John, and together they designed many buildings, including Fort George, near Inverness, and the home of Lord Dumfries in Ayrshire. In houses, they tended to continue their father’s Palladian style, but even at this stage Robert began to introduce interiors which were somewhat lighter and airier in design, and in which the ornamentation had something of a Rococo flavour.

xxxxxThe Scotsman Robert Adam was one of the most outstanding British architects and designers of the late 18th century. He was born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, but soon after his birth his family moved to Edinburgh. He attended the High School there and then, like his three brothers, was trained by his father William Adam, a leading Scottish architect of his day. When his father died in 1748, he worked with his older brother John, and together they designed many buildings, including Fort George, near Inverness, and the home of Lord Dumfries in Ayrshire. In houses, they tended to continue their father’s Palladian style, but even at this stage Robert began to introduce interiors which were somewhat lighter and airier in design, and in which the ornamentation had something of a Rococo flavour.

xxxxxIn 1754 Robert went on an extensive tour of Italy to make a close study of ancient Roman architecture. There was much renewed interest in antiquity at this time - due in large part to the excavation work going on at Pompeii and Herculaneum - and this was to have a marked effect on the course of his career. He journeyed to Florence and then Rome, where he was much impressed by the work of the French draftsman Charles-Louis Clerisseau and the Italian engraver Giovanni Battista Piranesi (who dedicated an engraving and book to him). Then, anxious to study private as well as public works, he journeyed to Dalmatia via Venice, and visited the ruins of Emperor Diocletian’s huge palace at Spalato (or Split), then part of the Venetian Republic. Here he spent five weeks making detailed drawings of the ancient remains.

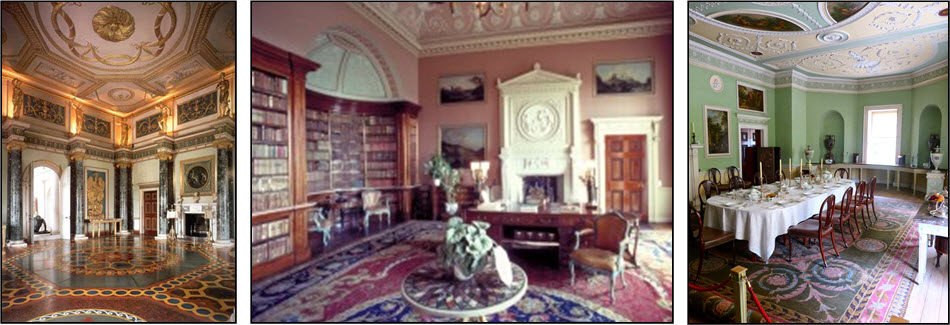

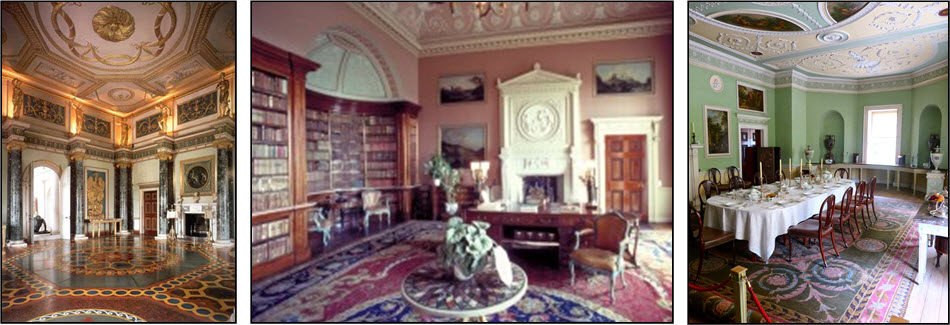

xxxxxOn his return to London in 1758, he soon established a thriving business. He was appointed joint architect to the king in 1762, and he was joined by his younger brother James the following year. With his assistance (and with occasional help from his brothers John and William) he built a number of fine houses in London and outside - such as No. 20 Portman Square (now the Courtauld Institute of Art), and Mersham-le-Hatch in Kent. However, the majority of his work involved remodelling existing stately homes on neo-classical or “Georgian” lines, like Osterley Park and Syon House just outside the capital, Harewood House in Yorkshire, Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire, and Saltram House, near Plymouth, in Devon. In these works he modified the somewhat heavy Palladian style, providing a greater feeling of spaciousness, and using more imagination and freedom in the choice of decoration. Shown here is an example of the interior decoration at Osterley Park House in Hounslow, a western suburb of London.

xxxxxOn his return to London in 1758, he soon established a thriving business. He was appointed joint architect to the king in 1762, and he was joined by his younger brother James the following year. With his assistance (and with occasional help from his brothers John and William) he built a number of fine houses in London and outside - such as No. 20 Portman Square (now the Courtauld Institute of Art), and Mersham-le-Hatch in Kent. However, the majority of his work involved remodelling existing stately homes on neo-classical or “Georgian” lines, like Osterley Park and Syon House just outside the capital, Harewood House in Yorkshire, Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire, and Saltram House, near Plymouth, in Devon. In these works he modified the somewhat heavy Palladian style, providing a greater feeling of spaciousness, and using more imagination and freedom in the choice of decoration. Shown here is an example of the interior decoration at Osterley Park House in Hounslow, a western suburb of London.

xxxxxAnd it was around the late 1760s that the brothers embarked on the development of that part of London which stretches from the Strand to the River Thames. Named Adelphi (from the Greek word for “brothers”), this town planning scheme included terraces of elegant houses as well as docks and warehouses along the waterfront (illustrated). But the “Adelphi scheme”, planned over a stretch of swamp land, proved extremely expensive once started. The brothers very nearly went bankrupt, and only managed to save the situation by running a lottery to finance the work’s completion. The scheme was finished in 1774, but the district was virtually rebuilt in the 1930s - though traces of the original buildings are still to be found.

xxxxxShown here (left to right) are the Ante Room in Sion House, London, the Library in Harewood House, Yorkshire, and the Dining Room in Saltram House, Devon.

Including:

The Greek Revival,

Neoclassicism and

William Chambers

This Greek revival was part of the movement known as Neoclassicism, a reaction against the frivolity of rococo and baroque art. Its regard for “noble simplicity and calm grandeur” stemmed mainly from the excavation of the Roman sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum, beginning in the 1740s, and from the writings of the German art historian Johann Winckelmann. In its early stages it was particularly applied to the decorative arts - to be seen, for example, in the work of the English designer Robert Adam and the English pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood. In furniture, too, the English cabinetmakers Chippendale, Hepplewhite and Sheraton adopted this style, as did the German cabinetmakers Riesener and Roentgen for Louis XVI. In painting, the greatest exponents, the French artists David and Ingres, came later in the century, as did the sculptors Canova, Thorvaldsen and Houdon. In architecture, this noble, imposing style was adopted widely in Europe and North America, the new republics of the United States and France using Greco-Roman facades to help convey a feeling of permanency and democratic government.

xxxxxBut whether they built from scratch or redeveloped an existing house, the brothers’ architectural plan included all the interior furnishings and ornamentation down to the last detail. As a result, their interior  designs were remarkable for their classical simplicity and symmetry, their ancient Greek as well as Roman motifs - achieved in delicate stucco decoration on walls and ceiling - and for their soft, distinctive pastel shades. It was, in fact, the creation of what came to be known as the “Adam style”, a lighter and freer style that complemented to perfection the elegant, well-proportioned rooms associated with the Georgian period. Indeed, the Adam brothers were the first to claim that the interior design of a building was the rightful concern of the architect. As a consequence they - and particularly Robert - designed everything from furniture to metalwork, and textiles to carpets as part of a unified scheme. Robert was himself a talented furniture designer and his style was popularised by the cabinetmaker George Hepplewhite. Thomas Sheraton was also greatly influenced by the elegance of the Adam style, and Thomas Chippendale created some of his finest furniture in collaboration with the Adam brothers.

designs were remarkable for their classical simplicity and symmetry, their ancient Greek as well as Roman motifs - achieved in delicate stucco decoration on walls and ceiling - and for their soft, distinctive pastel shades. It was, in fact, the creation of what came to be known as the “Adam style”, a lighter and freer style that complemented to perfection the elegant, well-proportioned rooms associated with the Georgian period. Indeed, the Adam brothers were the first to claim that the interior design of a building was the rightful concern of the architect. As a consequence they - and particularly Robert - designed everything from furniture to metalwork, and textiles to carpets as part of a unified scheme. Robert was himself a talented furniture designer and his style was popularised by the cabinetmaker George Hepplewhite. Thomas Sheraton was also greatly influenced by the elegance of the Adam style, and Thomas Chippendale created some of his finest furniture in collaboration with the Adam brothers.

XxxxxThe “Adam style” spread far and wide, assisted by two informative publications, the Ruins of the Palace of Diocletian in Dalmatia, produced by Robert in 1764, and Works in Architecture, written together with his brother James some ten years later (and with a second volume in 1779). InxAmerica it became known as the “Federal Style”, and was widely in vogue from 1780 to 1820, whilst in Russia, the Scottish architect Charles Cameron (1745-1812), seen as an imaginative designer of a new style, introduced it to the court of Catherine the Great and her successors.

XxxxxThe “Adam style” spread far and wide, assisted by two informative publications, the Ruins of the Palace of Diocletian in Dalmatia, produced by Robert in 1764, and Works in Architecture, written together with his brother James some ten years later (and with a second volume in 1779). InxAmerica it became known as the “Federal Style”, and was widely in vogue from 1780 to 1820, whilst in Russia, the Scottish architect Charles Cameron (1745-1812), seen as an imaginative designer of a new style, introduced it to the court of Catherine the Great and her successors.

xxxxxTowards the end of his life Robert Adam spent a great deal of time in Scotland. He produced some fine civic buildings, such as the Register House in Edinburgh and the city’s University, designed in 1789, but he also built a number of romantic, neo-Gothic castles, such as Culzean Castle in Ayrshire (illustrated). It is likely that the long journeys he undertook at this time, plus his refusal to cut down on his work load, took their toll on his health. He died at the age of 64, and was buried in Westminster Abbey. Most of his drawings, some 9,000 in total, are now in the Soane Museum, London.

xxxxxIncidentally, the Adam style proved extremely popular, but it was not universally admired. The English painter Sir Joshua Reynolds and the English actor David Garrick (1717-1779) were amongst the many who spoke highly of its elegance and grandeur, but there were those who disliked its sweeping, classical lines. Dr Johnson, for example, on visiting Kedleston Hall, declared that it was better fitted for a Town Hall than a country house, whilst the writer Horace Walpole, speaking of Robert’s applied decoration, described it as “gingerbread” and “snippets of embroidery”.

xxxxxThe Greek revival in architecture - seen in Robert Adam’s use of Greek motifs and Ionic and Doric columns - was due to a number of works at this time. Thesexincluded Ruins of the most beautiful monuments in Greece, produced by the French architect Julien-David Leroy (1724-1803) in 1758, and The Antiquities of Athens, a series of publications which began to appear in 1762, compiled by the English architects Nicholas Revett (1720-1804) and James Stuart (1713-1788). These, together with the History of Ancient Art, produced in 1764 by the influential German art historian Johann Winckelmann, created widespread enthusiasm for all that was Hellenic. And this interest was heightened in 1816 with the arrival in London of the Parthenon sculptures, popularly known as the “Elgin Marbles”.

xxxxxThe Greek revival in architecture - seen in Robert Adam’s use of Greek motifs and Ionic and Doric columns - was due to a number of works at this time. Thesexincluded Ruins of the most beautiful monuments in Greece, produced by the French architect Julien-David Leroy (1724-1803) in 1758, and The Antiquities of Athens, a series of publications which began to appear in 1762, compiled by the English architects Nicholas Revett (1720-1804) and James Stuart (1713-1788). These, together with the History of Ancient Art, produced in 1764 by the influential German art historian Johann Winckelmann, created widespread enthusiasm for all that was Hellenic. And this interest was heightened in 1816 with the arrival in London of the Parthenon sculptures, popularly known as the “Elgin Marbles”.

xxxxxThis Greek revival was all part of the wider movement known as Neoclassicism, a reaction against the sensuality and frivolity of rococo art, as well as the fussy excesses of the baroque art and architecture of the previous century. As we have seen, an interest in the “noble simplicity and calm grandeur” of antiquity was aroused in the 1740s. It was then that work started in earnest on the excavation of the Roman sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum - creating an immense interest in all things Roman - and it was then that the Italian engraver Giovanni Battista Piranesi began to produce his brilliant series of prints depicting the ruins of ancient Rome itself. Then in 1755 came the study of Greek painting and sculpture by the German art historian Johann Winckelmann (mentioned above), followed by his influential History of the Art of Antiquity, published in 1764. The message was clear: Greco-Roman art deserved to be studied and imitated for its timeless beauty, its noble, solemn form, and its measured restraint.

xxxxxImitated it certainly was. Originating in Western Europe, by the mid-19th century the movement - particularly evident in architecture, painting and the decorative arts - had spread throughout the rest of Europe and into Russia and the United States. In Britain, as we have seen, the interior designer Robert Adam and his brothers made ample use of classical pillars, capitals and motifs, whilst in 1768 the porcelain manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood built his new factory at Etruria for the sole purpose of producing ornamental pottery in the neo-classical style. Here the talented artist John Flaxman excelled at decorating “Greek” vases with graceful, silhouetted figures. The same trend can be seen in furniture making. Thomas Chippendale, in his later years, turned to classical design, as did the two German cabinetmakers Jean Henri Riesener and David Roentgen, whose elegant pieces contributed to the Louis XVI style in France.

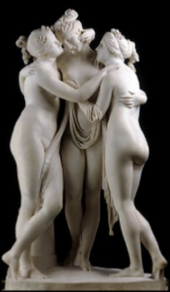

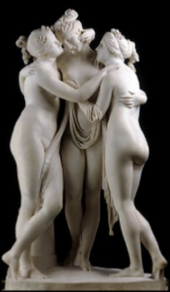

xxxxxIn painting, three men stand out in the early phases of the movement: the German Anton Raphael Mengs, the American Benjamin West, and the Scot Gavin Hamilton, all members of Winckelmann’s circle of friends in Rome. Exemplifying the style by its calm air of grandeur and harmony is Parnassus, a ceiling fresco produced by Mengs in 1761 for the Villa Albani in Rome. But, as we shall see, the greatest exponent of neo-classical painting was yet to come, the French painter Jacques Louis David, to be followed closely in time and talent by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. Likewise in sculpture, the major contributors belonged to the latter part of the century, and included the Italian Antonio Canova, the Dane Bertel Thorvaldsen, and the Frenchman Jean Antoine Houdon. Shown here is Canova’s The Three Graces.

xxxxxBut it was in architecture, perhaps, that neoclassicism made its biggest visual impact. Here, a style from the past, introduced as early as 1554 by the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, was often used to enhance the present. The newly formed republics in North America and France, for example, used the powerful facades of Greco-Roman design to create a feeling of grandeur, permanency and opulence. And in most people’s minds, such imposing buildings were vaguely associated with a well-ordered civilised and democratic state. (Illustrated here is the Capitol at Washington.) In America such designs came to be known as the “Federal style”, whilst in France, Napoleon’s impressive building programme in Paris was said to be in the “Empire style”f, and included a few triumphal arches to be in keeping with his imperial status. In England the style - often referred to as Georgian or Regency - was used for public buildings, such as the Bank of England and the British Museum, where much use was made of the Greek Ionic order.

xxxxxBut it was in architecture, perhaps, that neoclassicism made its biggest visual impact. Here, a style from the past, introduced as early as 1554 by the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, was often used to enhance the present. The newly formed republics in North America and France, for example, used the powerful facades of Greco-Roman design to create a feeling of grandeur, permanency and opulence. And in most people’s minds, such imposing buildings were vaguely associated with a well-ordered civilised and democratic state. (Illustrated here is the Capitol at Washington.) In America such designs came to be known as the “Federal style”, whilst in France, Napoleon’s impressive building programme in Paris was said to be in the “Empire style”f, and included a few triumphal arches to be in keeping with his imperial status. In England the style - often referred to as Georgian or Regency - was used for public buildings, such as the Bank of England and the British Museum, where much use was made of the Greek Ionic order.

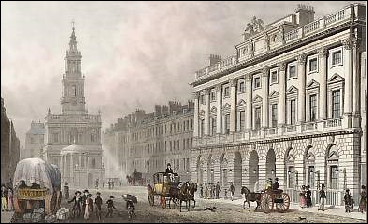

William Chambers (1723-1796) was one of the leading neo-classical architects working in England during this period. He was responsible for the design of Somerset House in London, begun in 1776, and he also designed a number of private houses in the same style. He served jointly with Robert Adam as architect to the king, and was seen by Robert as his principal rival. He travelled to China as a teenager, but in 1749 turned to architecture, studying in Paris and Rome. He came to the public notice in the late 1750s with his building of the orangery and the exotic pagoda at Kew, based on his travels in China. A founder member of the Royal Academy of Arts, his major works were Designs of Chinese Buildings and A Treatise on Civil Architecture, published in 1759.

xxxxxWilliam Chambers (1723-1796) was one of the leading neo-classical architects working in England at this time. Regarded by Robert Adam as his principal rival, in 1762 they shared the appointment of architect to the King’s works. Chambers was born in Goteborg, Sweden, where his father was a merchant of Scottish descent. He was educated in England, but at the age of 16 joined the Swedish East India Company, travelling to the Far East and visiting Canton. In 1749 he turned to architecture, and, after studying in Paris and Rome, was appointed architectural tutor to the Prince of Wales, the future George III, in 1755.

xxxxxWilliam Chambers (1723-1796) was one of the leading neo-classical architects working in England at this time. Regarded by Robert Adam as his principal rival, in 1762 they shared the appointment of architect to the King’s works. Chambers was born in Goteborg, Sweden, where his father was a merchant of Scottish descent. He was educated in England, but at the age of 16 joined the Swedish East India Company, travelling to the Far East and visiting Canton. In 1749 he turned to architecture, and, after studying in Paris and Rome, was appointed architectural tutor to the Prince of Wales, the future George III, in 1755.

xxxxxThis was the start of a highly successful career. Two years later he published his Designs of Chinese Buildings, based on his travels in China, and began his work on the famous exotic pagoda at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, a landmark which popularised the taste for chinoiserie. Here he also designed the orangery, a fine example of Georgian architecture. It was while working on these projects that he produced his A Treatise on Civil Architecture, a work which had a marked influence on current design.

xxxxxThis was the start of a highly successful career. Two years later he published his Designs of Chinese Buildings, based on his travels in China, and began his work on the famous exotic pagoda at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, a landmark which popularised the taste for chinoiserie. Here he also designed the orangery, a fine example of Georgian architecture. It was while working on these projects that he produced his A Treatise on Civil Architecture, a work which had a marked influence on current design.

xxxxxIn his public buildings he practised a refined neo-classical style. His best known work in London was the massive Somerset House, begun in 1776 and designed with Inigo Jones in mind (illustrated above). He also built Duddingston House in Edinburgh, Lord Bessborough’s villa at Roehampton, and the casino at Marino, near Dublin. Below is his sketch of the pagoda at Kew Gardens, and a view of the village of Milton Abbas in Dorset. In 1780 the local landowner, Lord Milton, decided that the village of Middleton was too close to his estate. He commissioned Chambers to design and build a new, purpose-built village - Milton Abbas - about half a mile to the south-east of Milton Abbey. He then re-allocated the villagers, destroyed Middleton, and employed Capability Brown to landscape the area! This is doubtless the first example in England of “town planning”, albeit on a small scale.

Chambers was a founder member of the Royal Academy in 1768 and, two years later, was appointed its first treasurer. He was allowed to assume the title of an English knight after receiving the knighthood of the polar star from the king of Sweden.

xxxxxIncidentally, Robert Adam regarded Chambers as a dangerous rival. In a letter he sent from Rome during his tour of Italy he wrote: "Chambers, who has been here six years, is superior to me at present ... but I will have a fair trial for it, and expect to do as much in six months as he has done in as many years". ......

xxxxx...... Itxwas about this time that the English architect James Gandon (1743-1823) began to give parts of Dublin its Georgian appearance. He designed a number of neo-classical buildings in the city, including Four Courts and the Custom House, begun in 1781. In the meantime, a building programme in Edinburgh eventually earned the city the title of "Athens of the North".

xxxxxThe Scotsman Robert Adam was one of the most outstanding British architects and designers of the late 18th century. He was born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, but soon after his birth his family moved to Edinburgh. He attended the High School there and then, like his three brothers, was trained by his father William Adam, a leading Scottish architect of his day. When his father died in 1748, he worked with his older brother John, and together they designed many buildings, including Fort George, near Inverness, and the home of Lord Dumfries in Ayrshire. In houses, they tended to continue their father’s Palladian style, but even at this stage Robert began to introduce interiors which were somewhat lighter and airier in design, and in which the ornamentation had something of a Rococo flavour.

xxxxxThe Scotsman Robert Adam was one of the most outstanding British architects and designers of the late 18th century. He was born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, but soon after his birth his family moved to Edinburgh. He attended the High School there and then, like his three brothers, was trained by his father William Adam, a leading Scottish architect of his day. When his father died in 1748, he worked with his older brother John, and together they designed many buildings, including Fort George, near Inverness, and the home of Lord Dumfries in Ayrshire. In houses, they tended to continue their father’s Palladian style, but even at this stage Robert began to introduce interiors which were somewhat lighter and airier in design, and in which the ornamentation had something of a Rococo flavour. xxxxxOn his return to London in 1758, he soon established a thriving business. He was appointed joint architect to the king in 1762, and he was joined by his younger brother James the following year. With his assistance (and with occasional help from his brothers John and William) he built a number of fine houses in London and outside -

xxxxxOn his return to London in 1758, he soon established a thriving business. He was appointed joint architect to the king in 1762, and he was joined by his younger brother James the following year. With his assistance (and with occasional help from his brothers John and William) he built a number of fine houses in London and outside -

designs were remarkable for their classical simplicity and symmetry, their ancient Greek as well as Roman motifs -

designs were remarkable for their classical simplicity and symmetry, their ancient Greek as well as Roman motifs - XxxxxThe “Adam style” spread far and wide, assisted by two informative publications, the Ruins of the Palace of Diocletian in Dalmatia, produced by Robert in 1764, and Works in Architecture, written together with his brother James some ten years later (and with a second volume in 1779). InxAmerica it became known as the “Federal Style”, and was widely in vogue from 1780 to 1820, whilst in Russia, the Scottish architect Charles Cameron (1745-

XxxxxThe “Adam style” spread far and wide, assisted by two informative publications, the Ruins of the Palace of Diocletian in Dalmatia, produced by Robert in 1764, and Works in Architecture, written together with his brother James some ten years later (and with a second volume in 1779). InxAmerica it became known as the “Federal Style”, and was widely in vogue from 1780 to 1820, whilst in Russia, the Scottish architect Charles Cameron (1745-

xxxxxThe Greek revival in architecture -

xxxxxThe Greek revival in architecture -

xxxxxBut it was in architecture, perhaps, that neoclassicism made its biggest visual impact. Here, a style from the past, introduced as early as 1554 by the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, was often used to enhance the present. The newly formed republics in North America and France, for example, used the powerful facades of Greco-

xxxxxBut it was in architecture, perhaps, that neoclassicism made its biggest visual impact. Here, a style from the past, introduced as early as 1554 by the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, was often used to enhance the present. The newly formed republics in North America and France, for example, used the powerful facades of Greco- xxxxxWilliam Chambers (1723-

xxxxxWilliam Chambers (1723- xxxxxThis was the start of a highly successful career. Two years later he published his Designs of Chinese Buildings, based on his travels in China, and began his work on the famous exotic pagoda at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, a landmark which popularised the taste for chinoiserie. Here he also designed the orangery, a fine example of Georgian architecture. It was while working on these projects that he produced his A Treatise on Civil Architecture, a work which had a marked influence on current design.

xxxxxThis was the start of a highly successful career. Two years later he published his Designs of Chinese Buildings, based on his travels in China, and began his work on the famous exotic pagoda at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, a landmark which popularised the taste for chinoiserie. Here he also designed the orangery, a fine example of Georgian architecture. It was while working on these projects that he produced his A Treatise on Civil Architecture, a work which had a marked influence on current design.