THE ANGLO-

THE BATTLES OF ISANDLWANA AND ULUNDI 1879 (Vb)

Acknowledgements

Shaka: detail,

photograph by George Lindmark Studio, Chicago, Illinois. Cetshwayo: painting by the German artist Carl Rudolph Sohn

(1845-

xxxxxAs we have seen, the warrior chief King Shaka united

the Zulu Clans in 1817 (G3c), and by a regime of terror quickly formed a Zulu

homeland in present-

xxxxxAs we have seen, the warrior chief King Shaka united

the Zulu Clans in 1817 (G3c), and by a regime of terror quickly formed a Zulu

homeland in present-

xxxxxShaka was

succeeded by his half-

xxxxxButxthe Zulus remained a

major force in the area and were yet to be conquered. King Cetshwayo (1836-

xxxxxButxthe Zulus remained a

major force in the area and were yet to be conquered. King Cetshwayo (1836-

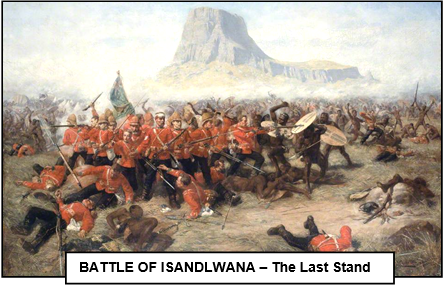

xxxxxAtxxfirst,

the invasion force was unopposed, but on 22nd January part

of the centre column, having advanced some eight miles beyond

Rorke’s Drift and set up a camp near the strange-

xxxxxAtxxfirst,

the invasion force was unopposed, but on 22nd January part

of the centre column, having advanced some eight miles beyond

Rorke’s Drift and set up a camp near the strange-

xxxxxNor was this the only setback for the British. In the meantime the column on the left flank, having crossed the Tugela River, had begun its march to Eshowe, a deserted missionary station which was to serve as an advanced base for the attack on Ulundi. Near the Ineyzane River, however, the column came under attack from some 6000 impis (warriors). This attack was successfully repulsed by accurate gunfire, including the use of a Gatling gun and seven pounders, and the column reached Eshowe the following day. There, however, the garrison of some l,300 men was soon surrounded, and the defences around the disused church and schoolroom had to be strengthened to withstand a siege. It was not, in fact, until the beginning of April that a relief column arrived, commanded by Lord Chelmsford. By then, 44 men had been killed and Zulu losses were well over a thousand.

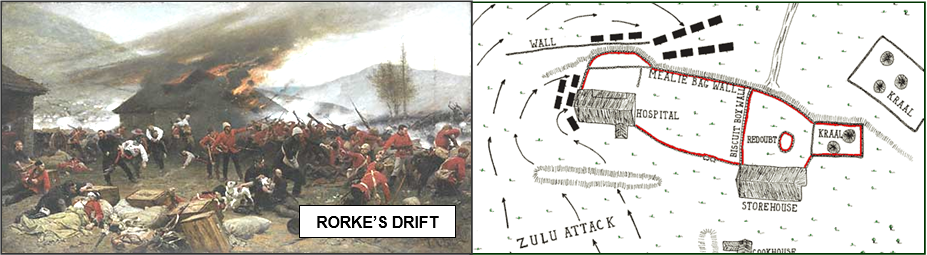

xxxxxAnd earlier,

following on from their victory at the Battle of Isandlwana, 4,000

Zulu reserves launched a raid on the nearby outpost of Rorke’s Drift, a trading

store and mission house that was being used as a field hospital.

They were only driven off after ten hours of ferocious fighting

during which 139 soldiers, making what could well have been their

last stand, inflicted heavy casualties upon their frenzied

attackers. The outer defences, made of biscuit boxes and bags of

grain, had to be abandoned after two hours, and when the hospital

was set on fire and its outer wall breached, holes had to be

smashed in the inner walls to drag the patients to safety. In the

hand-

Including:

Rorke’s Drift and

the Kaffir Wars.

Vb-

xxxxxAs we have

seen, King Shaka united the Zulu clans in 1817

(G3c) and, having made a highly efficient

army, embarked on a vicious campaign of expansion. By his death

the Zulus dominated most of South Africa from the Zambezi River to

Cape Colony. His half-

xxxxx(Thexpainting above is by Alphonse

de Neuville (1835-

xxxxxThe victory

at the Battle of Rorke’s Drift restored some faith in the fighting

ability of the British soldier, but the defeat at Isandlwana -

xxxxxThe decisive battle came at the beginning of July. In this renewed offensive the British army was made up of 12 infantry battalions, 2 cavalry regiments, 5 batteries of artillery comprising 24 guns, and a Gatling (machine gun) battery, the first of its kind. The total number of regular troops alone amounted to close on 2,000. And in addition to this enormous show of strength, a number of senior generals, including Sir Garnet Wolseley, were on their way to replace Lord Chelmsford!

xxxxxOn July 1st the bulk of this army crossed the White

Mfonzi River and Chelmsford, confident in his strength of numbers

and enormous fire power, formed a fortified square within sight of

Ulundi, the Zulu’s chief city. Within a short time a number of

cavalry skirmishes had enticed the Zulus to battle. Some 24,000

impis attacked the hollow square on all sides, but it was

slaughter on a pitiful scale. The combined fire of rifle, Gatling

guns and artillery prevented the warriors -

xxxxxOn July 1st the bulk of this army crossed the White

Mfonzi River and Chelmsford, confident in his strength of numbers

and enormous fire power, formed a fortified square within sight of

Ulundi, the Zulu’s chief city. Within a short time a number of

cavalry skirmishes had enticed the Zulus to battle. Some 24,000

impis attacked the hollow square on all sides, but it was

slaughter on a pitiful scale. The combined fire of rifle, Gatling

guns and artillery prevented the warriors -

xxxxxIncidentally, the last king of the Zulus, Cetshwayo, was captured a few weeks after the Battle of Ulundi. He was exiled to Cape Town, a prisoner on Robben Island, but in the summer of 1882 he spent nearly a month in London, where he met prime minister Gladstone and visited Queen Victoria at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. He was made ruler of central Zululand in January 1883, but he was not accepted by some of the other chiefs and became a fugitive. He died at Eshowe in 1884, and his grave, deep in the Nkandla forest, is maintained as a sacred place by the Zulus. ……

xxxxx…… The man who provoked the war, Sir Henry Bartle Frere,

was demoted and censured when it was over. The government of the

Transvaal and Natal was taken from him, and he was recalled to

England in July 1880. He was preparing to counter charges made

against him when he died in Wimbledon, South-

xxxxx…… An early and notable casualty of the war was the exiled heir to the French throne Prince Imperial Napoleon Eugene, only legitimate son of Napoleon III (who had abdicated in 1871). He volunteered to serve with the British Army and, wearing the uniform of the Royal Artillery, was killed whilst on a reconnaissance mission on the first day of June 1879. ……

xxxxx…… Contrary to popular belief, only a few of the defenders at Rorke’s Drift (meaning “ford”) were Welsh. The Regiment did not become a Welsh Regiment until two years after this historic battle. However, it does seem a fact that, when the assault on the mission house began, Sergeant Henry Gallagher shouted out, “Here they come, as thick as grass and as black as thunder”.

xxxxxThe year 1879 also saw the end of the Kaffir Wars. As we have seen, these began in 1779 (G3a) when the Boers came into conflict with the group of tribes known as the Xhosa. After the Boers made their Great Trek northwards in 1836, the British continued the fight against these native people, but it was not until 1852 (Va), during the eighth Kaffir War of 1850 to 1853, that they began to get the upper hand. In 1857 the Xhosa, persuaded by a prophecy, slaughtered all their cattle and destroyed all their crops, and this seriously weakened them as a nation. In the ninth war, 1877 to 1878, they were finally defeated at the Battles of Umzintanzani and Quintana, and in 1879 they and their land were incorporated into Cape Colony.

xxxxxThe year

1879 also saw the end of the Kaffir

Wars (known also as the Cape Frontier

Wars or Xhosa Wars). As we have seen, these began in 1779 (G3a) when the Boers

(Dutch farmers of South Africa), moving inland, came into conflict

with a group of tribes known as the Xhosa. This held up the

advance of the Boers for some years but eventually, when they made

their Great Trek northwards in 1836, they outflanked the Xhosa (arrowed on map) and left the

British to continue the fight alone. This they did, but the going proved

tough. The terrain was rugged, making movement slow and difficult,

and the Xhosa could take cover in the thick undergrowth and dense

forests. From there they were able to launch guerrilla attacks.

The British were forced to build forts to protect the eastern

frontier of Cape Colony, and it was not until 1852

(Va) during the eighth Kaffir War of 1850

to 1853, that they began to get the better of their formidable

enemy.

xxxxxThe year

1879 also saw the end of the Kaffir

Wars (known also as the Cape Frontier

Wars or Xhosa Wars). As we have seen, these began in 1779 (G3a) when the Boers

(Dutch farmers of South Africa), moving inland, came into conflict

with a group of tribes known as the Xhosa. This held up the

advance of the Boers for some years but eventually, when they made

their Great Trek northwards in 1836, they outflanked the Xhosa (arrowed on map) and left the

British to continue the fight alone. This they did, but the going proved

tough. The terrain was rugged, making movement slow and difficult,

and the Xhosa could take cover in the thick undergrowth and dense

forests. From there they were able to launch guerrilla attacks.

The British were forced to build forts to protect the eastern

frontier of Cape Colony, and it was not until 1852

(Va) during the eighth Kaffir War of 1850

to 1853, that they began to get the better of their formidable

enemy.

xxxxxThen in 1857

the Xhosa people themselves brought about their final collapse. In

that year they were persuaded by a prophecy to slaughter all their

cattle and destroy all their crops in the belief that this would

raise their ancestors from their graves and bring about the

destruction of the British. They never recovered from this self-