xxxxxThe French writer Émile Zola gained his first notable success with his novel Thérèse Raquin of 1867, a grim story of passion and murder, but it was his series of 20 novels known as Les Rougon-Macquart, begun in 1871, which brought him fame and fortune. In this family saga, stretching over five generations, he aimed, by a detached, scientific approach, to study the effects of hereditary and environment upon the characters of his creation. In this “naturalistic” approach, as he termed it, he saw the need to study in close detail and over a wide range of settings the vices and weaknesses of his time. Thus his novels were often sordid and lurid, peopled with thieves, prostitutes, drunkards and misfits from the squalid life of the working class. The Drunkard, for example, was a study of alcoholism; Nana of 1880, followed the life of a prostitute; The Earth, a story of greed, was crude and obscene in parts; The Human Animal was full of passion and madness; and The Downfall described the horrors and chaos of the Franco-Prussian War. These “social documents”, by their appraisal of human behaviour, had a marked influence on the development of the modern novel. Today, however, Zola is also remembered for the prominent part he played in the Dreyfus Affair of 1894 (Vc). As we shall see, his vigorous support of the young Jewish army officer, wrongly accused of treason, won him international fame. Zola was a close friend of the artists Paul Cézanne and Éduard Manet, and wrote in favour of the Impressionist movement. He numbered among his literary friends Guy de Maupassant, Gustave Flaubert, the Goncourt brothers, Alphonse Daudet and the Russian Ivan Turgenev.

ÉMILE ZOLA 1840 - 1902 (W4, Va, Vb, Vc, E7)

Acknowledgements

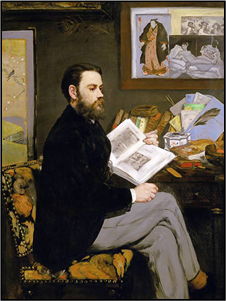

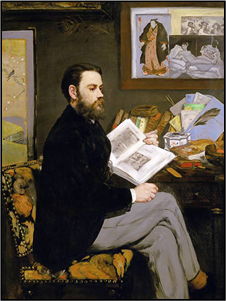

Zola: by the French painter Édouard Manet (1832-1883), 1868 – Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Rozerot: photograph by Émile Zola, date unknown – Château d’Eau, Toulouse, France. Huysmans: pastel by the French impressionist painter Jean-Louis Forain (1852-1931), 19th century – Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, France.

xxxxxThe French novelist and social reformer Émile Zola came to prominence as a writer with his Thérèse Raquin of 1867, a grim story of passion and murder. Four years later, following the end of the Franco-Prussian War, he embarked upon a series of twenty novels centred around the fortunes of two branches of a French family during the Second Empire. Contained in a collection known as Les Rougon-Macquart, these inter-related novels - aiming to show in depth the significant part played by hereditary and environment in the shaping of human character - were seen as experiments in sociology, and put him at the head of what the French termed “literary naturalism”. Later, as we shall see, Zola was to become deeply involved in national politics when he attacked the military establishment for their complicity in the so-called Dreyfus Affair of 1894.

xxxxxThe French novelist and social reformer Émile Zola came to prominence as a writer with his Thérèse Raquin of 1867, a grim story of passion and murder. Four years later, following the end of the Franco-Prussian War, he embarked upon a series of twenty novels centred around the fortunes of two branches of a French family during the Second Empire. Contained in a collection known as Les Rougon-Macquart, these inter-related novels - aiming to show in depth the significant part played by hereditary and environment in the shaping of human character - were seen as experiments in sociology, and put him at the head of what the French termed “literary naturalism”. Later, as we shall see, Zola was to become deeply involved in national politics when he attacked the military establishment for their complicity in the so-called Dreyfus Affair of 1894.

xxxxxZola was born in Paris, the son of Francesco Zola, an Italian civil engineer, and Émile Aubert, the daughter of a glazier. When he was three years old the family moved to Aix-en-Province and it was there, as a pupil at the Collège de Bourbon, that he met and became a long-term friend of the young artist-to-be Paul Cézanne. After the death of his father, he and his mother returned to Paris in 1858. There they lived in abject poverty until, in 1862, he eventually managed to gain employment with Hachette, the well-known publishing house. He made progress there, but in his spare time he turned to writing verse and short stories. His Tales of Ninon of 1864 had little success, but the following year his  Claude’s Confession - a sordid tale complete with bedroom scenes - brought him to the notice of the public … and the police. In 1866 he left his job to become a free-lance journalist, and over the next four years he wrote literary and art reviews, and, as a political observer, made plain his dislike of Emperor Napoleon III. It was during this period, in 1867, that he published his first major novel Thérèse Raquin. The success of this shocking catalogue of murder, suicide and psychological torture - all detailed in pursuance of what he termed a scientific study of temperament - convinced him that his future lay as a writer.

Claude’s Confession - a sordid tale complete with bedroom scenes - brought him to the notice of the public … and the police. In 1866 he left his job to become a free-lance journalist, and over the next four years he wrote literary and art reviews, and, as a political observer, made plain his dislike of Emperor Napoleon III. It was during this period, in 1867, that he published his first major novel Thérèse Raquin. The success of this shocking catalogue of murder, suicide and psychological torture - all detailed in pursuance of what he termed a scientific study of temperament - convinced him that his future lay as a writer.

xxxxxIn 1868 Zola conceived the idea of a series of novels, similar to Balzac’s The Human Comedy, but seen as a vehicle for his interest in genetics and psychological analysis. Unfortunately for him the Franco-Prussian War intervened. However, he sought safety in Marseilles, and returned at the end of the war to publish The Fortune of the Rougons, the first novel in the series Les Rougon-Macquart. Over the next twenty-two years he published a novel almost every year. Launched from what he called “the springboard of exact observation”, these novels attempted to explore the depths of human existence across a wide variety of social conditions in order to evaluate the part played by both heredity and environment in the development of human behaviour.

xxxxxHe called this new approach to fiction naturalism, an extension of realism which, in order to meet the needs of a pseudo-scientific experiment in sociology, required a penetrating, clinical study of the vices and weaknesses of his time. By creating characters of certain, distinct traits he felt able to trace the progressive effects of a variety of social ills - be it alcoholism, prostitution or gratuitous violence - throughout five generations of a single family. As a result, Zola’s novels, dealing in the main with the squalid life of the working-class, were often sordid and lurid in their detail, peopled with thieves, prostitutes, the mentally retarded, drunkards, and an assortment of misfits. Popular though such works proved to be, they came in for some strong criticism, mainly on the grounds of their obscenity. In 1887, for example, The Earth, which included a crude account of peasant bestiality, prompted condemnation by a “group of five”, made up of his erstwhile disciples. In an article published in Le Figaro they denounced him as a pornographer.

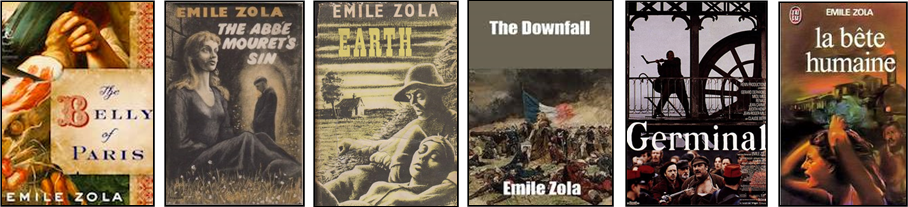

xxxxxThe Rougon-Macquart series, which aimed to provide a “social and natural history” of France during the Second Empire, established his reputation as a realist writer of outstanding talent. During his career he wrote on a wide variety of subjects, but it is these social documents by which he is best known and valued today. Amongst his best-known novels in this family saga are The Belly of Paris (Le Ventre de Paris), centred around the lives of those who worked at Les Halles, the huge market place in Paris; The Abbé Mouret’s Sin, a modern version of the Genesis story; The Drunkard (L’Assommoir), a study of alcoholism, noted for its vulgarity and brutality; Nana of 1880, a risqué novel - for its day - telling the life story of a prostitute; The Stew (Pot-Bouille), recording the sleazy goings-on behind the respectable façade of an apartment block in Paris; Germinal, a graphic account of the dreadful conditions within the mining communities of northern France and the effect these living conditions had upon the miners themselves; The Earth, a story of greed within a struggling farming community; The Human Animal, (La Bête Humaine), a psychological thriller full of passion and madness, played out on the stretch of railway between Paris and Le Havre, and The Downfall (La Débâcle), a vivid description of the collapse of the Second Empire amid the chaos and horrors of the Franco-Prussian War.

xxxxxThe Rougon-Macquart series, which aimed to provide a “social and natural history” of France during the Second Empire, established his reputation as a realist writer of outstanding talent. During his career he wrote on a wide variety of subjects, but it is these social documents by which he is best known and valued today. Amongst his best-known novels in this family saga are The Belly of Paris (Le Ventre de Paris), centred around the lives of those who worked at Les Halles, the huge market place in Paris; The Abbé Mouret’s Sin, a modern version of the Genesis story; The Drunkard (L’Assommoir), a study of alcoholism, noted for its vulgarity and brutality; Nana of 1880, a risqué novel - for its day - telling the life story of a prostitute; The Stew (Pot-Bouille), recording the sleazy goings-on behind the respectable façade of an apartment block in Paris; Germinal, a graphic account of the dreadful conditions within the mining communities of northern France and the effect these living conditions had upon the miners themselves; The Earth, a story of greed within a struggling farming community; The Human Animal, (La Bête Humaine), a psychological thriller full of passion and madness, played out on the stretch of railway between Paris and Le Havre, and The Downfall (La Débâcle), a vivid description of the collapse of the Second Empire amid the chaos and horrors of the Franco-Prussian War.

Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb-1862-1880-Vb

xxxxxFollowing the publication of L’Assommoir in 1878 - one of his most successful novels - he bought a large house at Médan, a village on the Seine west of Paris. It was here in 1880 that together with five of his disciples, including the writer Guy de Maupassant, he produced a volume of short, naturalist stories about the Franco-Prussian War entitled Les Soirées de Médan. By that time Zola was a well-known figure in the literary world, numbering among his friends Gustave Flaubert, the Goncourt brothers, Alphonse Daudet and Ivan Turgenev.

xxxxxZola’s later works, such as the trilogy The Three Cities (1894-1898) and the unfinished The Four Gospels (1899-1902), lacked the intensity of his earlier novels. Both plot and character formation became subordinate to the exposition of his socialist philosophy and his rejection of Roman Catholicism. And to this period belongs a number of works attacking the romantics - his literary opponents -, and several treatises explaining his theory of naturalism, such as The Experimental Novel and a collection of essays entitled The Naturalistic Fiction Writers.

xxxxxZola’s novels - particularly the Rougon-Macquart series - had an enormous influence on the development of modern literature, both by their diversity of subject and their blunt, scientific exposition of human behaviour. His “social documents”, wide in scale and vision, provided the launching pad for the naturalistic novel, a literary by-product of Darwin’s theory of evolution. But, sociology aside, Zola’s novels also testify to his powerful concern for truth and social justice. As we shall see, this was to become fully apparent when, in the so-called Dreyfus Affair of 1894 (Vc), he came out publicly in support of a young Jewish artillery officer whom, he claimed, had been wrongly accused of high treason. It was a courageous thing to do, and there are those who believe that it cost him his life. Indeed, Zola is remembered today as much for his J’accuse - his open letter in defence of Dreyfus - as for his outstanding contribution to world literature.

xxxxxZola’s novels - particularly the Rougon-Macquart series - had an enormous influence on the development of modern literature, both by their diversity of subject and their blunt, scientific exposition of human behaviour. His “social documents”, wide in scale and vision, provided the launching pad for the naturalistic novel, a literary by-product of Darwin’s theory of evolution. But, sociology aside, Zola’s novels also testify to his powerful concern for truth and social justice. As we shall see, this was to become fully apparent when, in the so-called Dreyfus Affair of 1894 (Vc), he came out publicly in support of a young Jewish artillery officer whom, he claimed, had been wrongly accused of high treason. It was a courageous thing to do, and there are those who believe that it cost him his life. Indeed, Zola is remembered today as much for his J’accuse - his open letter in defence of Dreyfus - as for his outstanding contribution to world literature.

xxxxxIt would seem that Zola died of a tragic accident in 1902, killed by fumes from a bedroom fire, though many at the time believed that the chimney was deliberately blocked by anti-Dreyfusards as an act of revenge for the vital part he played in the support of the young Jewish officer. He had certainly made enemies during the affair, but tributes to his literary works and his courage flooded in from all parts of France. He was buried in Montmartre Cemetery, Paris, but in 1908 his remains were moved to the Panthéon where he shared a crypt with Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas.

xxxxxIncidentally, Zola’s wife Alexandrine, whom he married in 1870, survived him. His two children, Denise and Jacques, were the product of his long affair with his wife’s housemaid Jeanne Rozerot, who became his mistress in 1888. This photograph of her was taken by Zola himself. He became a keen photographer towards the end of his life. ……

xxxxx…… Because of his close friendship with Cézanne, Zola became a staunch supporter of Impressionism, and got to know a number of the movement’s leading members. He frequently visited the Café Guerbois, where they met, and in 1866, as a freelance journalist, he wrote a series of articles praising the works of Édouard Manet and Claude Monet, and criticising the narrow mindedness of the Salon’s selection committee. Two years later, to show his gratitude, Manet painted Zola’s portrait (illustrated above), shown at the Salon of 1868. In 1886, however, his friendship with the Impressionists came to an abrupt end. His novel of that year, The Masterpiece, contained a far from sympathetic portrayal of the Bohemian life of a typical painter, and this offended a number of his artist friends, including Cézanne.

xxxxxThe French decadent novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907) was a close friend of Émile Zola and a member of his literary circle. His early novels, notably Marthe, The Vatard Sisters, and Dowmstream, were very much in the naturalist style popularised by Zola. In 1884, however, utterly bored and disgusted with modern life, he produced Against the Grain (À rebours) and this work firmly placed him in the French Decadent Movement. Its hero Des Esseintes - Huysmans in fact - abandons his life of sensuous pleasures and shuts himself away to indulge in the delights of sight, taste and smell. His imagination then conjures up a strange mixture of fantasies, nightmares and sinister or erotic visions. In 1891 another controversial novel appeared, The Damned, a study of Satanism, but after this Huysmans was “saved” by a return to his Catholic faith, recorded in his works En route and La Cathédrale in the late 1890s. Huysmans was also a respected art critic and his two books Modern Art and Certains were well received. Like Zola, he was an early supporter of French Impressionism.

xxxxxA contemporary French writer who was a friend of Émile Zola and knew him well, was the decadent novelist and art critic Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907). Early on, his realistic novels were admired by Zola, but his later works, notably his scandalous Against Nature of 1884, and his disquieting The Damned of 1891, attracted his displeasure, despite their popularity at large. Huysmans’ rich style of writing is not always easy to follow, but he possessed remarkable powers of description and a caustic, satirical wit.

xxxxxA contemporary French writer who was a friend of Émile Zola and knew him well, was the decadent novelist and art critic Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907). Early on, his realistic novels were admired by Zola, but his later works, notably his scandalous Against Nature of 1884, and his disquieting The Damned of 1891, attracted his displeasure, despite their popularity at large. Huysmans’ rich style of writing is not always easy to follow, but he possessed remarkable powers of description and a caustic, satirical wit.

xxxxxHis first publication of note, his Dish of Spices of 1874 - a collection of prose poems much influenced by the works of his fellow countryman Charles Baudelaire - received some favourable reviews, but it was his realistic novel Marthe, published two years later, that brought him to the attention of a wider public. Based around the life of a young prostitute, it found favour with Zola, as did his next three works, The Vatard Sisters (Les Soeurs Vatard), Married Life (En Ménage) and Downstream (À vau-l’eau). Based around the sordid, gloomy and commonplace lives of working class heroes, these novels were firmly in the naturalist style popularised by Zola.

xxxxxBut by 1883, Huysmans’ disgust and distaste for modern life, and his deep pessimism brought a change in direction. Utterly bored with his existence, and finding Zola’s “naturalism” shallow and restrictive, he produced his Against the Grain (À rebours) the following year, and put himself firmly in the French Decadent Movement. Its hero, the Duc Jean des Esseintes - Huysmans in all but name - being totally fed up with city life, abandons his “unnatural loves and perverse pleasures” and shuts himself away from the world to indulge in the delights aroused by sight, taste and smell. His imagination conjures up a potpourri of bizarre fantasies, strange nightmares, and sinister or erotic visions. “The heavy odour of incense”, wrote the Irish playwright Oscar Wilde, “seemed to cling about its pages and trouble the brain”.

xxxxxBut by 1883, Huysmans’ disgust and distaste for modern life, and his deep pessimism brought a change in direction. Utterly bored with his existence, and finding Zola’s “naturalism” shallow and restrictive, he produced his Against the Grain (À rebours) the following year, and put himself firmly in the French Decadent Movement. Its hero, the Duc Jean des Esseintes - Huysmans in all but name - being totally fed up with city life, abandons his “unnatural loves and perverse pleasures” and shuts himself away from the world to indulge in the delights aroused by sight, taste and smell. His imagination conjures up a potpourri of bizarre fantasies, strange nightmares, and sinister or erotic visions. “The heavy odour of incense”, wrote the Irish playwright Oscar Wilde, “seemed to cling about its pages and trouble the brain”.

xxxxxEventually Huysmans found “salvation” by a return to faith. After dabbling with Satanism and the occult in his The Damned (Là-Bas) - a passing fad in the Parisian society of his day - he records his conversion to Roman Catholicism, guided by his new hero Durtal (his fictional alter ego) in works such as En route in 1895 and La Cathédrale three years later. Then in 1898, after resigning from his humdrum civil service job, a post he had held along side his writing for 32 years, he retired to Liguge in Poitou and for two years lived the life of a Benedictine monk. In 1905 he was diagnosed with cancer of the mouth, and died in Paris two years later.

xxxxxApart from his work as a novelist, Huysmans was also a recognised art critic, and gained fame with his two books, Modern Art in 1883 and Certains in 1889. And, like Zola, he was, from the beginning, a strong supporter of the Impressionist movement and a severe critic of the Salon de Paris. He was also one of the founders of the Goncourt Academy, established in 1903 to encourage French literature, and served as its first president. Apart from Zola, Huysmans numbered among his friends and acquaintances the French writers Gustave Flaubert, Edmond Goncourt and Guy de Maupassant, and the French poets Paul Verlaine and Stéphane Mallarmé.

xxxxxIncidentally, Huysmans served for a while in the Franco-Prussian War, and was caught up in the horrors of both the siege of Paris and the Paris Commune. His short novel The Knapsack (Sac au dos), described his experiences during this time, and the story was published, along with other war stories, in Les Soirées de Médan, produced in 1880 by Zola and some of his friends. ……

xxxxx…… Huysmans’ novel The Damned (a study of Satanism) had the dubious distinction of being cited during the trial of Oscar Wilde in 1895. It was then referred to as a “sodomitical” book. And it also played a part in Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, being known there as the “poisonous” yellow book.

Including:

Joris-Karl

Huysmans

xxxxxThe French novelist and social reformer Émile Zola came to prominence as a writer with his Thérèse Raquin of 1867, a grim story of passion and murder. Four years later, following the end of the Franco-

xxxxxThe French novelist and social reformer Émile Zola came to prominence as a writer with his Thérèse Raquin of 1867, a grim story of passion and murder. Four years later, following the end of the Franco- Claude’s Confession -

Claude’s Confession -

xxxxxThe Rougon-

xxxxxThe Rougon- xxxxxZola’s novels -

xxxxxZola’s novels -

xxxxxA contemporary French writer who was a friend of Émile Zola and knew him well, was the decadent novelist and art critic Joris-

xxxxxA contemporary French writer who was a friend of Émile Zola and knew him well, was the decadent novelist and art critic Joris-

xxxxxBut by 1883, Huysmans’ disgust and distaste for modern life, and his deep pessimism brought a change in direction. Utterly bored with his existence, and finding Zola’s “naturalism” shallow and restrictive, he produced his Against the Grain (À rebours) the following year, and put himself firmly in the French Decadent Movement. Its hero, the Duc Jean des Esseintes -

xxxxxBut by 1883, Huysmans’ disgust and distaste for modern life, and his deep pessimism brought a change in direction. Utterly bored with his existence, and finding Zola’s “naturalism” shallow and restrictive, he produced his Against the Grain (À rebours) the following year, and put himself firmly in the French Decadent Movement. Its hero, the Duc Jean des Esseintes -