THE WAR AT SEA

THE BATTLE OF JUTLAND: 31st MAY – 1st JUNE 1916

Acknowledgements

Location Map: eyewitnesstohistory.co Map of Battle: battlesofww1.weebly.com Battle Scene: artuk.org by English artist Robert Henry Smith Sinking of Indefatigable: britishbattles.com by German artist Willy Stower Losses: twitter.com Bulldog: loc.gov Tribune Graphic Scheer: en.numista.com Jellicoe: bbc.co.uk Beatty: fineartamerica.con February 1917: youtubel.com

The Battle of Jutland was by far the most significant naval battle of the First World War. As we have seen, there were earlier conflicts at sea – such as the Battles of Coronel and the Falkland Islands off the coast of South America, and, in home waters, the Battles of Heligoland and Dogger Bank – but it was only at Jutland that the dreadnought battleships of both sides actually came face to face. Involving 250 ships and around 100,000 men, it was the largest, bloodiest and most controversial naval battle of its time .. and beyond!

The Battle of Jutland was by far the most significant naval battle of the First World War. As we have seen, there were earlier conflicts at sea – such as the Battles of Coronel and the Falkland Islands off the coast of South America, and, in home waters, the Battles of Heligoland and Dogger Bank – but it was only at Jutland that the dreadnought battleships of both sides actually came face to face. Involving 250 ships and around 100,000 men, it was the largest, bloodiest and most controversial naval battle of its time .. and beyond!

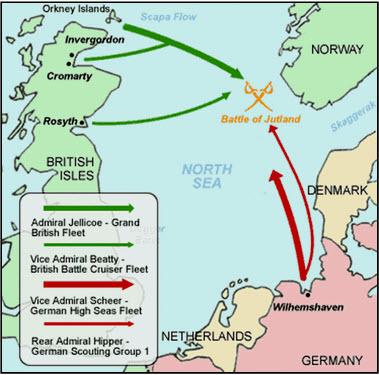

In essence, it was a German attempt to ease if not eradicate the British trade blockade of material and food which was slowly but surely crippling the German Empire. The plan was to lure out the British Battlecruiser Squadron (stationed at Rosyth under the command of Admiral Sir David Beatty), put it out of action, and then take on and defeat the larger part of the British Grand Fleet (commanded by Admiral Sir John Jellico), when – summoned to assist – it arrived from its distant base in the Orkney Islands (see map below). It was a highly ambitious scheme as it stood, but it was made the more perilous by the fact that, unknown to the Germans, the British had been warned by their codebreakers that the operation was in the offing, thereby ensuring that, when the trap was about to be sprung, Jellico’s force would already be well on its way to the battle zone. Combined, the two British forces would number 151 ships compared with the 99 available to the Germans. This said, the German High Seas Fleet was no mean force, comprising 24 battleships, 5 battle cruisers, 11 light cruisers and 63 destroyers.

It was early on the 31st May that the German fleet, under the command of Admiral Reinhard Scheer (a man anxious to take on the enemy) entered the North Sea and, as planned, enticed the British Battle Cruiser Force to leave their base at Rosyth and confront the bulk of the German fleet, waiting some 75 miles off the west coast of Jutland (Skaggerak in German). The result was a one-

It was early on the 31st May that the German fleet, under the command of Admiral Reinhard Scheer (a man anxious to take on the enemy) entered the North Sea and, as planned, enticed the British Battle Cruiser Force to leave their base at Rosyth and confront the bulk of the German fleet, waiting some 75 miles off the west coast of Jutland (Skaggerak in German). The result was a one-

WW1-

To go back to the Dateline, click HERE

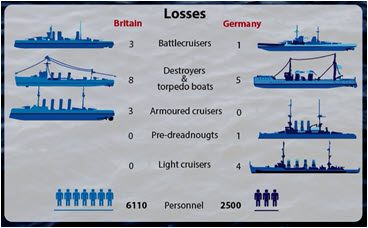

The German navy lost eleven ships, including a battleship and a battle cruiser, and a number of its ships were badly damaged. Casualties amounted to some 2,500. The British sustained heavier loses, fourteen ships in total, including three battle cruisers, and with casualties put at 6,110. On paper, it was a German victory, and it was seen as such by press and public. In Germany, there was much rejoicing, and the Kaiser boasted that “the spell of Trafalgar is broken”. In Britain, of course, there was bitter disappointment at the poor showing of the most powerful navy in the world. But, from a strategic point of view, whilst the Royal Navy lost more ships and more men, it retained its dominance in the North Sea, and was able to continue the blockade, a major contribution to Germany’s eventual defeat. On June 2nd the Grand Fleet was ready for action, but the German High Seas Fleet spent many months repairing its  damaged vessels, and never again challenged British control of the North Sea. As one New York newspaper put it, the German fleet had assaulted its jailer, but it was still in jail. And the New York Tribune Graphic (11th June, 1916) had no doubt about the victor (see pic below). Indeed, on the 4th July 1916, Admiral Sheer himself informed the German High Command that, because of Britain’s “great material superiority”, further fleet action was not an option. As he saw it, unrestricted submarine warfare was the best and only hope of achieving victory at sea.

damaged vessels, and never again challenged British control of the North Sea. As one New York newspaper put it, the German fleet had assaulted its jailer, but it was still in jail. And the New York Tribune Graphic (11th June, 1916) had no doubt about the victor (see pic below). Indeed, on the 4th July 1916, Admiral Sheer himself informed the German High Command that, because of Britain’s “great material superiority”, further fleet action was not an option. As he saw it, unrestricted submarine warfare was the best and only hope of achieving victory at sea.

Nevertheless, as was to be expected, the leadership of both Jellicoe and Beaty was questioned. Winston Churchill, former Chief of the Admiralty, bluntly declared that Jellicoe was the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon! Others openly accused him of being too cautious and lacking in initiative. Beaty, on the other hand, was taken to task for his vanity and “glory seeking”. But others argued that both men knew exactly what was required and, by a show of strength which put their ships at greater risk, drove the German High Seas Fleet back to dry land and kept it there for the rest of the war. And there was criticism, too, – some well founded – about the hardware itself. In the midst of the battle, Beaty himself had declared “there seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today”. In the case of HMS Indefatigable and Queen Mary, both violently blown up, it was suggested flash protection of the magazines was inadequate; the way ammunition was handled was seen as a contributory factor in the loss of three battle cruisers; a number of the leading ships appeared to be insufficiently armoured; and the lack of reliable communications – a major criticism following the Battle of Heligoland in August 1914 – continued to raise problems concerning the essential need for overall command.

Nevertheless, as was to be expected, the leadership of both Jellicoe and Beaty was questioned. Winston Churchill, former Chief of the Admiralty, bluntly declared that Jellicoe was the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon! Others openly accused him of being too cautious and lacking in initiative. Beaty, on the other hand, was taken to task for his vanity and “glory seeking”. But others argued that both men knew exactly what was required and, by a show of strength which put their ships at greater risk, drove the German High Seas Fleet back to dry land and kept it there for the rest of the war. And there was criticism, too, – some well founded – about the hardware itself. In the midst of the battle, Beaty himself had declared “there seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today”. In the case of HMS Indefatigable and Queen Mary, both violently blown up, it was suggested flash protection of the magazines was inadequate; the way ammunition was handled was seen as a contributory factor in the loss of three battle cruisers; a number of the leading ships appeared to be insufficiently armoured; and the lack of reliable communications – a major criticism following the Battle of Heligoland in August 1914 – continued to raise problems concerning the essential need for overall command.

AdmiralxReinhard Scheer (1863-

AdmiralxReinhard Scheer (1863-

...... AdmiralxSir John Jellicoe (1859-

...... AdmiralxSir John Jellicoe (1859-

...... Admiral Sir David Beatty (1871-

...... Admiral Sir David Beatty (1871-

The Battle of Jutland confirmed the important role to be played by the U-

The Battle of Jutland confirmed the important role to be played by the U-