xxxxxThe Englishman John Wesley

was ordained in 1728. On returning to Oxford as a tutor, he and his

brother Charles were members of the Holy Club, a group of so-

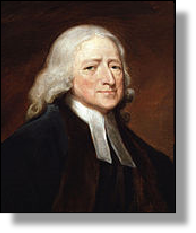

JOHN WESLEY 1703 -

THE FOUNDATION OF METHODISM

Acknowledgements

John Wesley: by

the English portrait painter George Romney (1734-

G2-

xxxxxJohn Wesley, the founder of Methodism, was

born in Epworth, Lincolnshire, where his father was the rector. He

attended Charterhouse School before going up to Christ Church, Oxford,

in 1720. He was ordained in the Church of England in 1728, and the

following year returned to Oxford as a fellow of Lincoln College. It

was here that, together with his brother Charles and, later, his

friend George Whitefield, he was a member and then leader of the Holy

Club, a group of religious-

xxxxxJohn Wesley, the founder of Methodism, was

born in Epworth, Lincolnshire, where his father was the rector. He

attended Charterhouse School before going up to Christ Church, Oxford,

in 1720. He was ordained in the Church of England in 1728, and the

following year returned to Oxford as a fellow of Lincoln College. It

was here that, together with his brother Charles and, later, his

friend George Whitefield, he was a member and then leader of the Holy

Club, a group of religious-

xxxxxIn 1735, together with his

brother Charles and the evangelist George Whitefield, he travelled

as a missionary to Georgia, the colony only recently established by

James Oglethorpe in North America. Save for his meeting with some

German Moravians, who impressed him with their piety and spiritual

peace, the trip was a disaster. His high church views were not well

received, and his missionary work among the Indians met with

failure. He sailed back to England in December 1737, a disappointed

man, but in May the following year, while attending a Moravian

service in London, his "heart was strangely warmed" and he

experienced what he described as his conversion to evangelism. This

"Aldersgate Street Experience", as he later termed it, convinced him

that his mission was to preach the simple message that a person

could be saved by faith alone. This dictum being opposed by a large

number of Anglican clergy, the following year he joined in the work

of the evangelist George Whitefield, and Methodism was born. In a

very short time he had gained a reputation throughout the country

for the passion and fervour he brought to his open-

xxxxxOver the next

fifty years he rode across the country on horseback, reaching out to

the masses and converting thousands to the Christian faith by his

simple, direct message. It is estimated that he travelled some 5,000

miles each year and gave an average of four sermons a day. The sermons

he gave on these occasions, together with his notes on the New

Testament, formed the basis of the Methodist doctrine. Hisxtheology

was greatly influenced by A Serious Call to a

Devout and Holy Life, the work of the

English cleric William Law (1686-

xxxxxOver the next

fifty years he rode across the country on horseback, reaching out to

the masses and converting thousands to the Christian faith by his

simple, direct message. It is estimated that he travelled some 5,000

miles each year and gave an average of four sermons a day. The sermons

he gave on these occasions, together with his notes on the New

Testament, formed the basis of the Methodist doctrine. Hisxtheology

was greatly influenced by A Serious Call to a

Devout and Holy Life, the work of the

English cleric William Law (1686-

xxxxxThe early success of this spiritual revolution clearly called for the setting up of a nation wide organisation. As early as 1739 the first Methodist society was formed in London, and its eventual meeting place, a building called the Foundry, became the headquarters of the movement for many years. Societies then began to be set up throughout the country. In 1742 these societies were themselves divided into districts and circuits, many led by lay preachers, and two years later the first conference of Methodist leaders was held, and this became an annual event. By this time, however, the movement had begun to form its own specific doctrine. This had led to a split with the Moravians and with George Whitefield, a Calvinist who believed in the doctrine of predestination.

xxxxxBut the Methodist movement remained within

the Church of England for some years ahead, despite Wesley's rejection

of the apostolic succession. Indeed, it was not until 1784 that the

separation became virtually inevitable. It was then that he issued a

Deed of Declaration, a legal constitution setting out the guidelines

to be followed by the societies, and in the same year he himself

ordained his aide, Thomas Coke, for service in the United States. When

this was followed by other "ordinations" the break with the Anglican

church was just a matter of time. It came in 1795, four years after

Wesley's death, when the Methodist Conference authorised their

preachers to administer the sacraments even though they had not been

ordained by the Church of England. This proved a step too far.

xxxxxBut the Methodist movement remained within

the Church of England for some years ahead, despite Wesley's rejection

of the apostolic succession. Indeed, it was not until 1784 that the

separation became virtually inevitable. It was then that he issued a

Deed of Declaration, a legal constitution setting out the guidelines

to be followed by the societies, and in the same year he himself

ordained his aide, Thomas Coke, for service in the United States. When

this was followed by other "ordinations" the break with the Anglican

church was just a matter of time. It came in 1795, four years after

Wesley's death, when the Methodist Conference authorised their

preachers to administer the sacraments even though they had not been

ordained by the Church of England. This proved a step too far.

xxxxxThroughout his life as a

preacher Wesley showed a deep concern for the advancement and well-

xxxxxHe died in March 1791, and was buried in the graveyard of City Road Chapel in London. A memorial plaque to him was placed in Westminster Abbey, a clear indication that, by that time, much of the heat had gone out of the hostility once shown to him by high church members of the Church of England. At his death it was estimated that converts to his faith numbered 70,000.

xxxxxMethodism today has some 40 million members

worldwide, the largest number being in the United States, where a

separate church was founded in 1784. A number of doctrinal disputes

caused divisions in the 19th century, but these were reconciled at a

conference in London in 1932, when the Wesleyan, Primitive and United

Methodists were formed into the Methodist Church. In its early years

in particular, the movement provided spiritual comfort for large

numbers of working-

xxxxxMethodism today has some 40 million members

worldwide, the largest number being in the United States, where a

separate church was founded in 1784. A number of doctrinal disputes

caused divisions in the 19th century, but these were reconciled at a

conference in London in 1932, when the Wesleyan, Primitive and United

Methodists were formed into the Methodist Church. In its early years

in particular, the movement provided spiritual comfort for large

numbers of working-

xxxxxCharles Wesley (1707-

xxxxxThe English

evangelist George Whitefield (1714-

xxxxxThe English

evangelist George Whitefield (1714-

xxxxxJohn Wesley joined Whitefield as an

itinerant preacher in 1739, and, together, they turned the Methodist

movement in the British Isles into something of a spiritual

revolution. But the working relationship between the two men was not

destined to last. Whitefield was a Calvinist, believing in

predestination, whereas Wesley held the views of the Dutch Protestant

Jacobus Arminius, a man totally opposed to this doctrine. In about

1741 they parted company, though they remained friends. After this

break, Whitefield became recognised as the leader of the Calvinistic

Methodists. He died in 1770 whilst on one of his preaching tours in

the American colonies. It is said that during his career he preached

more than 18,000 sermons.

xxxxxJohn Wesley joined Whitefield as an

itinerant preacher in 1739, and, together, they turned the Methodist

movement in the British Isles into something of a spiritual

revolution. But the working relationship between the two men was not

destined to last. Whitefield was a Calvinist, believing in

predestination, whereas Wesley held the views of the Dutch Protestant

Jacobus Arminius, a man totally opposed to this doctrine. In about

1741 they parted company, though they remained friends. After this

break, Whitefield became recognised as the leader of the Calvinistic

Methodists. He died in 1770 whilst on one of his preaching tours in

the American colonies. It is said that during his career he preached

more than 18,000 sermons.

xxxxxIncidentally,

Whitefield was cross-

Including:

Charles Wesley

and

George Whitefield

xxxxxAs we have seen, Charles

Wesley (1707-

xxxxxAs we have seen, Charles

Wesley (1707-

xxxxxCharles accompanied his brother to Georgia

in 1735, having taken holy orders in order to work as a missionary. On

arrival he acted as secretary to the colonial governor James

Oglethorpe, but the climate proved too much for him, and he returned

home within a few months. When Methodism began to expand in the 1740s,

he took an active part as an itinerant preacher, notably in London and

Bristol, but he was most anxious to keep the movement within the

Church of England, and strongly disapproved of John's ordination of

"clergy" for work in America. This, plus disagreement over family

matters, led to some measure of estrangement between the two brothers,

and in the late 1750s he began to take a smaller part in the

leadership of the movement.

xxxxxCharles accompanied his brother to Georgia

in 1735, having taken holy orders in order to work as a missionary. On

arrival he acted as secretary to the colonial governor James

Oglethorpe, but the climate proved too much for him, and he returned

home within a few months. When Methodism began to expand in the 1740s,

he took an active part as an itinerant preacher, notably in London and

Bristol, but he was most anxious to keep the movement within the

Church of England, and strongly disapproved of John's ordination of

"clergy" for work in America. This, plus disagreement over family

matters, led to some measure of estrangement between the two brothers,

and in the late 1750s he began to take a smaller part in the

leadership of the movement.

xxxxxIncidentally, his son Samuel was a composer and an accomplished organist. He wrote church and secular music and, like his father, produced a number of hymns.

xxxxxThe English evangelist George Whitefield (1714-