xxxxxThe science fiction writer and social theorist H.G. Wells produced his first major novel The Time Machine in 1895, and followed this with a series of scientific fantasies which included The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds and The First Men in the Moon, published in 1901.These highly successful novels, together with later works like The World Set Free and The Shape of Things to Come, predicted with uncanny accuracy many of the advances which were to take place in aviation, warfare, atomic research and space exploration. As a committed socialist he also wrote a number of comic novels, such as Love and Mr Lewisham, Kipps, and The History of Mr Polly, which, based on his own experience in a working class family, told of the struggle and frustrations of those who strove to better themselves in a class-

HERBERT GEORGE WELLS 1866 -

(Vb, Vc, E7, G5, G6)

Acknowledgements

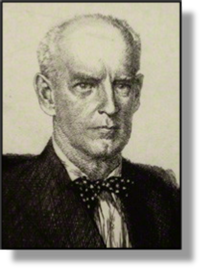

Wells: detail, by the Irish studio photographer George Charles Beresford (1864-

XxxxxThe English writer and social theorist Herbert George Wells, known simply as H.G. Wells, was, like his contemporary the French author Jules Verne, a leading pioneer in science fiction. His fantasy novels such as The Time Machine of 1895, The Invisible Man, produced the following year, and his famous The War of the Worlds, published in 1898, made him internationally famous. In these works and many of his others -

XxxxxThe English writer and social theorist Herbert George Wells, known simply as H.G. Wells, was, like his contemporary the French author Jules Verne, a leading pioneer in science fiction. His fantasy novels such as The Time Machine of 1895, The Invisible Man, produced the following year, and his famous The War of the Worlds, published in 1898, made him internationally famous. In these works and many of his others -

xxxxxWells was born in Bromley, Kent. His father played cricket for Kent and owned a small shop selling china and sports equipment, but when the business failed and his father broke his leg -

xxxxxIt was in 1895 that he produced his first successful novel entitled The Time Machine, a journey to a disturbing world wherein the human race had developed into two species, the feeble Eloi and the brutish Morlocks. This fascinating adventure into the unknown and its bizarre tale -

xxxxxThere followed in quick succession The Island of Dr. Moreau, centred around the strange world of the “Beast Folk”; The Invisible Man, the tale of a medical student who discovers a way of making himself invisible, causes mayhem in a quiet Sussex village, and eventually meets his end; The War of the Worlds, a hostile Martian invasion of our planet; and The First Men in the Moon, a flight of fancy which introduces the Selenites, insect-

xxxxxBut Wells, a committed socialist, also had his feet firmly on the ground. These fantasies were followed by a number of excellent social comedies in the early 1900s, such as Love and Mr Lewisham, Kipps, The Story of a Simple Soul, Ann Veronica (concerning the suffragette movement) and The History of Mr Polly. Drawn from his own memories as a member of a working class family, these novels certainly contain a fund of humour, but they also told - this collecti

this collecti on of social studies was his Mr. Britling Sees It Through, an astute study of the impact of the First World War upon the British public.

on of social studies was his Mr. Britling Sees It Through, an astute study of the impact of the First World War upon the British public.

xxxxxMeanwhile, firmly believing, initially, that the advances in science and technology - r candidate in the general elections of 1922 and 1923. However, with the coming of the First World War and the growing threat of a second conflagration in the 1930s, his hopes for an international society which would control man’s increasing powers of destruction faded fast. Later his worst fears were realised. He lived through the Second World War (1939-

r candidate in the general elections of 1922 and 1923. However, with the coming of the First World War and the growing threat of a second conflagration in the 1930s, his hopes for an international society which would control man’s increasing powers of destruction faded fast. Later his worst fears were realised. He lived through the Second World War (1939-

xxxxxWells also wrote a wealth of entertaining shorts stories -

xxxxxWells produced more than 80 books on a wide variety of subjects. He wrote in a simple direct style, but he possessed great descriptive and narrative skills, and a distinctive ability to stir the imagination. Today he is best remembered for his science fiction novels and the way in which he anticipated many of scientific inventions yet to come, but in his own day he was also respected for the sympathy and understanding he showed towards ordinary people -

xxxxxAnd alongside his fight for social equality and world peace went a revolt against what he regarded as outmoded conventions, particularly with regard to sex. In his books and in his personal life he showed a firm belief in individual freedom. In all these respects his influence was considerable. Wells died in London in August 1946. He had earlier stated that his epitaph should read: “I told you so, you damned fools!”, but in the event he was cremated and his ashes scattered at sea!

xxxxxIncidentally, Wells made a large number of friends, but he was not adverse to quarrelling with some of them. As a member of the Fabian Society in the early 1900s, for example, he tried to expel the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw, then one of its leaders, on the grounds that the Society was not radical enough, and his novel Boon, published in 1915, included a bitter parody of the American novelist Henry James. ……

xxxxx…… Wells met both Lenin and Stalin, the communist leaders of the Soviet Union, but he was never a Marxist. He maintained that the tenets of Marxism were too restrictive and rigid for independent thought. In 1906 he travelled to the United States and had a friendly meeting with the American President Theodore Roosevelt. ……

x xxxx…… In October 1938 a radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds, thought by many to be a genuine news broadcast, caused widespread panic in the United States. The story itself might well have been inspired by the work of the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli. As we have seen, in 1877 he claimed that he had discovered “canals” on the surface of Mars, giving rise to the possibility of there being some form of advanced life on the red planet. ……

xxxx…… In October 1938 a radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds, thought by many to be a genuine news broadcast, caused widespread panic in the United States. The story itself might well have been inspired by the work of the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli. As we have seen, in 1877 he claimed that he had discovered “canals” on the surface of Mars, giving rise to the possibility of there being some form of advanced life on the red planet. ……

xxxxx…… Wells married his cousin Isabel Mary Wells in 1891, but left her for one of his students, Catherine Robbins, three years later. They married in 1895 and had two sons, but throughout his life he had a large number of “liaisons”, including scandalous affairs with the feminist writers Amber Reeves and Rebecca West and the children they begat! ……

xxxxx…… TwoxBritish writers who were beginning their careers towards the end of the century and were befriended by Wells, were John Galsworthy and Joseph Conrad. They met in Adelaide, Australia, in 1893, when Galsworthy was travelling on family business and Conrad was serving as first mate aboard the sailing boat Torrens.

xxxxxJohn Galsworthy (1867-

xxxxxJohn Galsworthy (1867-

xxxxxJoseph Conrad (1857- went to sea as a lad of 17 and landed at Lowestoft, Suffolk, in 1878 at the age of 21. It was then that he began to learn English, a language he mastered with surprising ease. He became a naturalised British subject in 1886, and in 1894, having retired from the

went to sea as a lad of 17 and landed at Lowestoft, Suffolk, in 1878 at the age of 21. It was then that he began to learn English, a language he mastered with surprising ease. He became a naturalised British subject in 1886, and in 1894, having retired from the  sea, settled in Kent.

sea, settled in Kent.

xxxxxThere, encouraged by Galsworthy and H.G. Wells, he began to write in earnest. He published An Outcast of the Islands in 1896, and Nigger of the Narcissus a year later, and these were followed by a number of popular works, including Lord Jim (1900), Heart of Darkness (1902), Typhoon (1903), Nostromo (1904), The Secret Agent (1907), Chance (1912), The Rescue (1920) and The Rover (1922). Many of his novels and short stories were based on his experience at sea and set in exotic places. Adventure, however, was always combined with a profound study of human psychology in which human weakness was contrasted with human courage in the face of challenging situations. His Heart of Darkness, based on his own experience as the captain of a steamer on the Congo River, came to be seen as a powerful indictment of the evils of colonialism.

Vc-

Including:

John Galsworthy

and Joseph Conrad