xxxxxIn 1809, inspired by the popular Spanish and Portuguese uprisings against French rule, the Austrians - still smarting from their humiliating defeats at Ulm and Austerlitz in 1805 - declared war on Napoleon. The Austrian army fared well at first, defeating the French at the battle of Aspern-Essling on the Danube, but when the two armies met again at Wagram, ten miles north-east of Vienna in July 1809, Napoleon gained yet another victory. Having crossed the Danube, his first attack was repulsed, and the next morning a counterattack pushed back the French line. However, Napoleon then called up his artillery and, at the same time, launched an attack on the northern front which outflanked the enemy. The concentrated gunfire caused heavy casualties, and the Austrians were forced to retreat. By the late afternoon, this retreat had turned into a rout. By the Treaty of Schönbrunn the Austrians lost 30,000 square miles, but an agreed marriage between Napoleon and Marie-Louise, daughter of the Austrian Emperor Francis I, brought a rapprochement between the two nations, and Austria survived to fight another day.

THE NAPOLEONIC WARS 1803 - 1815 (G3c)

THE BATTLE OF WAGRAM 1809

Acknowledgements

Metternich: by the English portrait painter Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), 1814/19 – Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Wagram: by the French painter Horace Vernet (1789-1863), 1836 – Galerie des Battailles, Versailles. Marie-Louise: detail, by the French painter Jean Baptiste Isabey (1767-1855), 1810 – Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Hofer: detail, by the German painter Geoge Wachter (1762-1852), 1839/40 – State Museum of Brunswick, Lower Saxony, Germany. Execution: c1810, artist unknown. Appert: contained in Les Artisans Illustres by the French writer Édouard Foucaud, 1841, artist unknown, photo by Jean Paul Barbier – Musée des Beaux Arts, Châlons, Champagne, France.

xxxxxAs we have seen, in 1807, determined to maintain his Continental System, Napoleon invaded Portugal to enforce the blockade against the British. Then a year later to ensure access to that country, he seized control of Spain, putting his brother Joseph on the Spanish throne. As a result, both countries rebelled against the French occupation; the British sent an army to support them; and Napoleon had the Peninsular War on his hands.

xxxxxTo Austria, humiliated by the defeats of Ulm and Austerlitz in 1805, this seemed the long-awaited opportunity to strike back at the French. The Austrians had rebuilt their army over the intervening years, and their minister to France at this time, the astute Count Metternich (illustrated), - overestimating, as it turned out, this new threat against the French - urged the Austrian government to take military action. The foreign secretary at the time, Johann Philipp von Stadion, needed no persuasion. Inspired by the popular rising of the Spanish and Portuguese, he persuaded his Emperor and the country that the hour for revenge and retribution had arrived. Austria mobilised and declared war on France in April 1809.

xxxxxTo Austria, humiliated by the defeats of Ulm and Austerlitz in 1805, this seemed the long-awaited opportunity to strike back at the French. The Austrians had rebuilt their army over the intervening years, and their minister to France at this time, the astute Count Metternich (illustrated), - overestimating, as it turned out, this new threat against the French - urged the Austrian government to take military action. The foreign secretary at the time, Johann Philipp von Stadion, needed no persuasion. Inspired by the popular rising of the Spanish and Portuguese, he persuaded his Emperor and the country that the hour for revenge and retribution had arrived. Austria mobilised and declared war on France in April 1809.

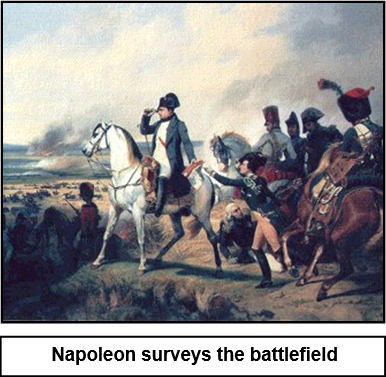

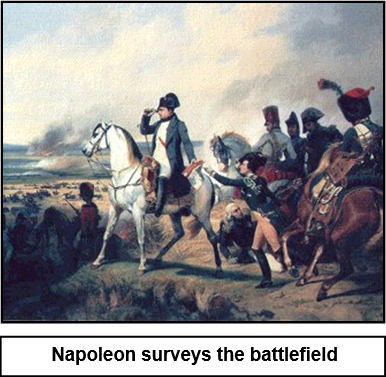

xxxxxThe immediate result was a French occupation of Vienna, but towards the end of May, at Aspern and Essling, just across the River Danube from the capital, the Austrian army, led by Archduke Charles, inflicted upon Napoleon his first major defeat on the battlefield. Unfortunately for them, however, the Austrians did not take advantage of their victory, and Napoleon, anxious to prevent a larger coalition forming against him, quickly regrouped and sought out his enemy. He found the Austrians deployed on the plain of Marchfeld, either side of the village of Wagram some ten miles north-east of Vienna.

xxxxxOn the afternoon of the 5th July 1809 he crossed over the Danube and launched his opening attack, but this was repulsed. Then on the morning of the next day the Austrians mounted a counterattack in the south, driving the French back for some considerable distance. But Napoleon then brought up his artillery. This caused heavy casualties and stopped the Austrian advance in the centre, whilst a French attack in the north managed to outmanoeuvre the enemy, causing confusion and bringing about a general retreat. Archduke John arrived with reinforcements in the late afternoon, but by this time the Austrians were in full flight, leaving behind some 40,000 casualties and prisoners. The French casualties were also high, about 34,000, but Napoleon had won the day and France remained in control of Germany. Four days later Archduke Charles sued for peace.

xxxxxOn the afternoon of the 5th July 1809 he crossed over the Danube and launched his opening attack, but this was repulsed. Then on the morning of the next day the Austrians mounted a counterattack in the south, driving the French back for some considerable distance. But Napoleon then brought up his artillery. This caused heavy casualties and stopped the Austrian advance in the centre, whilst a French attack in the north managed to outmanoeuvre the enemy, causing confusion and bringing about a general retreat. Archduke John arrived with reinforcements in the late afternoon, but by this time the Austrians were in full flight, leaving behind some 40,000 casualties and prisoners. The French casualties were also high, about 34,000, but Napoleon had won the day and France remained in control of Germany. Four days later Archduke Charles sued for peace.

xxxxxMetternich,xdespite his earlier misjudgment, was appointed foreign affairs minister by the Emperor in October 1809, and spoke for Austria at the Treaty of Schönbrunn. He attempted to soften the terms of the agreement, but Napoleon would have none of it. Austria lost over 30,000 square miles with a population of some three and a half million. Much of this went to France, including Istria and Trieste, and a part of Croatia; the Grand Duchy of Warsaw gained West Galicia; Bavaria obtained Salzburg and Berchtesgaden; and Russia, who had supported Napoleon as an ally, received part of East Galicia. In addition, Austria had to pay a large indemnity, reduce its army to 150,000, and join the Continental System.

xxxxxDespite these harsh terms, Metternich achieved quite a measure of success after Schönbrunn by deciding that if you cannot beat your enemy it is best to join him. With this in mind he managed to arrange a marriage between Marie-Louise (illustrated), daughter of Emperor Francis II, and Napoleon himself - anxious to stabilize his own infant dynasty. This not only brought about a rapprochement between the two nations, thereby keeping Austria in existence, but it also gave a much needed period of respite for a country which was totally exhausted and virtually bankrupt. He even went so far as to persuade his emperor to send troops in support of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812. As we shall see, by collaborating with the enemy, Austria lived to fight another day.

xxxxxDespite these harsh terms, Metternich achieved quite a measure of success after Schönbrunn by deciding that if you cannot beat your enemy it is best to join him. With this in mind he managed to arrange a marriage between Marie-Louise (illustrated), daughter of Emperor Francis II, and Napoleon himself - anxious to stabilize his own infant dynasty. This not only brought about a rapprochement between the two nations, thereby keeping Austria in existence, but it also gave a much needed period of respite for a country which was totally exhausted and virtually bankrupt. He even went so far as to persuade his emperor to send troops in support of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812. As we shall see, by collaborating with the enemy, Austria lived to fight another day.

Including:

Andreas Hofer

and Nicolas Appert

xxxxxLeading his own war of resistance at this time was the Tirolese patriot Andreas Hofer (1767-1810). Born in Saint Leonhard, South Tirol, in the Austrian Alps, he inherited his father’s inn and also traded in wine and cattle. In the war against France he was a sharp shooter, and one of the leaders in the local militia. When the Treaty of Pressburg of 1805 - which followed the Austrian defeats at Ulm and Austerlitz - handed the Tirol over to Bavaria, he organised a rebellion against his new masters, and soon became a local hero, leading a force of some 20,000. So successful was his campaign, that by 1808 he had driven out the Bavarian army. And when a Franco-Bavarian force invaded in 1809, his partisan army defeated it at Sterzing in the April, and then in two battles

xxxxxLeading his own war of resistance at this time was the Tirolese patriot Andreas Hofer (1767-1810). Born in Saint Leonhard, South Tirol, in the Austrian Alps, he inherited his father’s inn and also traded in wine and cattle. In the war against France he was a sharp shooter, and one of the leaders in the local militia. When the Treaty of Pressburg of 1805 - which followed the Austrian defeats at Ulm and Austerlitz - handed the Tirol over to Bavaria, he organised a rebellion against his new masters, and soon became a local hero, leading a force of some 20,000. So successful was his campaign, that by 1808 he had driven out the Bavarian army. And when a Franco-Bavarian force invaded in 1809, his partisan army defeated it at Sterzing in the April, and then in two battles fought at Iselberg the following month.

fought at Iselberg the following month.

xxxxxHofer then occupied Innsbruck and set up an administration with himself as governor and commander in chief. However, in spite of promises from Emperor Francis I that the Tirol would remain Austrian, after the defeat at Wagram in July 1809, the Treaty of Schönbrunn ceded the region to Napoleon, and the French moved into the area in force. Hofer and his men retreated into the mountains, and it was then that his whereabouts was betrayed to the French - possibly because of the rapprochement being developed between Napoleon and the House of Habsburg. He was captured at his camp in January 1810, taken to Mantua in Italy, and executed the following month.

xxxxxIncidentally, the remains of this national hero were brought back to Innsbruck in 1823, and buried in the Franciscan Church there. An account of his fight for freedom is the subject of a festival held each year in Iselberg, and a poem about him, Landwirth (Landowner) Hofer, written by the German poet Julius Mosen (1803-1867), still provides the words for the Tirolese anthem.

xxxxxFighting his own battles for Austria at this time was the Tirolese patriot Andreas Hofer (1767-1810) He led a resistance movement against the Bavarians when they acquired the Tirol by the Treaty of Pressburg in 1805. He managed to drive out the Bavarian army and, later, in 1809, he repelled an invasion by a French-Bavarian force. However, after the Treaty of Schönbrunn the French moved into the Tirol in force, and he was captured and executed. Today he is regarded as a national hero.

G3c-1802-1820-G3c-1802-1820-G3c-1802-1820-G3c-1802-1820-G3c-1802-1820-G3c

xxxxx It was in 1809 that the Parisian chef, Nicholas Appert (1749-1814) perfected a means of preserving food in sealed bottles. This invention, especially valuable for use at sea or when an army was on the march, won him a prize of 12,000 francs, offered in 1795 to anyone who could devise a practical method of preserving food. In 1810 he wrote a book about his invention and, two years later, opened up a factory at Massey, south of Paris, to supply the French army and navy. In 1810 an English inventor, Peter Durand, used tin-platted cans instead of bottles, and these soon became the best type of container. Appert adopted cans in 1822 and in the same year the “canning industry” opened up in the United States.

xxxxxIt was in 1809 that a Parisian chef, Nicolas Appert (1749-1814), perfected an idea which proved of enormous value to an army on the march and to ships at sea. In that year he invented a means of preserving food by partially cooking it, sealing it in glass bottles using cork and wire, and then immersing the bottles in boiling water for varying lengths of time. By such means he preserved a number of foods, including meat, vegetables, fruits, dairy products and soups.

xxxxxIt was in 1809 that a Parisian chef, Nicolas Appert (1749-1814), perfected an idea which proved of enormous value to an army on the march and to ships at sea. In that year he invented a means of preserving food by partially cooking it, sealing it in glass bottles using cork and wire, and then immersing the bottles in boiling water for varying lengths of time. By such means he preserved a number of foods, including meat, vegetables, fruits, dairy products and soups.

xxxxxThe need for such an invention had been recognised by the military as early as 1795, and in that year a reward was offered by the Directory to anyone who could devise a practical method of preserving food. Having carried out experiments over fourteen years and achieved just that, in 1810 Appert was awarded 12,000 francs by Napoleon and published a book about his method entitled The Art of Preserving All Kinds of Animal and Vegetable Substances for Several Years. Two years later, with the money he had made from his invention, he opened up a factory at Massey, south of Paris - the House of Appert - and this establishment, beginning with orders from the French navy, remained in business until 1933.

xxxxxAtxthe same time (1810) an English inventor, Peter Durand (1768-1855), took this preserving process a step further by using tin-plated cans instead of bottles, and by 1820 Bryan Donkins and John Hall were using his patent to supply tinned food to the British navy and army. Appert himself changed to this “canning” method in 1822, and three years later a Thomas Kensett, who in 1812 had set up a New York factory using bottles, began to use tins. It was to prove a very profitable business almost from the start. The Gold Rush of 1849 and the American Civil War (1861-65) created an enormous demand for this new product.

xxxxxTins proved much easier to make airtight, were stronger, and they were more speedily produced than bottles. In the early days four cans could be manufactured in a day, but production was quickly stepped up (today it is 400 a minute!). Inx1815 the German explorer Otto von Kotzebue (1787-1846) took some cans of food with him on his third navigation of the world and was well pleased with his “tin boxes”. The tin of roast veal illustrated above was taken by the English explorer William Parry on his voyage to the arctic in 1824. The instructions on the side read: “Cut round the top near to the outer edge with a chisel and hammer”! Edward J. Warner of Connecticut, United States, patented the first tin-opener in 1848!

xxxxxIncidentally, we are told that a tin of veal and peas, canned in England in 1818, was still fresh when opened in 1938!

xxxxxTo Austria, humiliated by the defeats of Ulm and Austerlitz in 1805, this seemed the long-

xxxxxTo Austria, humiliated by the defeats of Ulm and Austerlitz in 1805, this seemed the long- xxxxxOn the afternoon of the 5th July 1809 he crossed over the Danube and launched his opening attack, but this was repulsed. Then on the morning of the next day the Austrians mounted a counterattack in the south, driving the French back for some considerable distance. But Napoleon then brought up his artillery. This caused heavy casualties and stopped the Austrian advance in the centre, whilst a French attack in the north managed to outmanoeuvre the enemy, causing confusion and bringing about a general retreat. Archduke John arrived with reinforcements in the late afternoon, but by this time the Austrians were in full flight, leaving behind some 40,000 casualties and prisoners. The French casualties were also high, about 34,000, but Napoleon had won the day and France remained in control of Germany. Four days later Archduke Charles sued for peace.

xxxxxOn the afternoon of the 5th July 1809 he crossed over the Danube and launched his opening attack, but this was repulsed. Then on the morning of the next day the Austrians mounted a counterattack in the south, driving the French back for some considerable distance. But Napoleon then brought up his artillery. This caused heavy casualties and stopped the Austrian advance in the centre, whilst a French attack in the north managed to outmanoeuvre the enemy, causing confusion and bringing about a general retreat. Archduke John arrived with reinforcements in the late afternoon, but by this time the Austrians were in full flight, leaving behind some 40,000 casualties and prisoners. The French casualties were also high, about 34,000, but Napoleon had won the day and France remained in control of Germany. Four days later Archduke Charles sued for peace.  xxxxxDespite these harsh terms, Metternich achieved quite a measure of success after Schönbrunn by deciding that if you cannot beat your enemy it is best to join him. With this in mind he managed to arrange a marriage between Marie-

xxxxxDespite these harsh terms, Metternich achieved quite a measure of success after Schönbrunn by deciding that if you cannot beat your enemy it is best to join him. With this in mind he managed to arrange a marriage between Marie-

xxxxxLeading his own war of resistance at this time was the Tirolese patriot Andreas Hofer (1767-

xxxxxLeading his own war of resistance at this time was the Tirolese patriot Andreas Hofer (1767- fought at Iselberg the following month.

fought at Iselberg the following month.  xxxxxIt was in 1809 that a Parisian chef, Nicolas Appert (1749-

xxxxxIt was in 1809 that a Parisian chef, Nicolas Appert (1749-