xxxxxThe Congress of Vienna had as its task the reorganisation of Europe after the Napoleonic Wars. It took no account of the liberal ideas which had inspired the French Revolution, and it paid little attention to national self-

THE NAPOLEONIC WARS 1803 -

THE CONGRESS OF VIENNA 1814 -

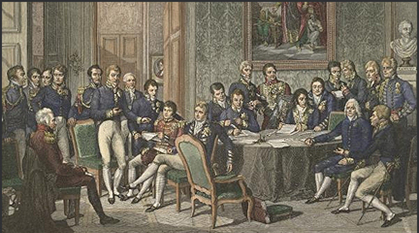

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Congress of Vienna opened in September 1814, five months after Napoleon’s abdication. Despite his sudden return to power in 1815, it completed its deliberations in June of that year, just a few days before the Battle of Waterloo and the final end to the Napoleonic Wars. The Congress had been convened following a preliminary agreement arrived at by the Treaty of Chaumont in March 1814. Austria was represented by Prince von Metternich, Prussia by Prince von Hardenburg, and Great Britain by its foreign minister Viscount Castlereagh (replaced later by the Duke of Wellington). The Tsar himself, Alexander I, attended on behalf of Russia, and Louis XVIII, the restored Bourbon monarch, appointed Charles Maurice de Talleyrand to negotiate on behalf of the French. Representatives were also sent from Spain, Portugal and Sweden, and some of the minor European states sent envoys to report back on the proceedings.

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Congress of Vienna opened in September 1814, five months after Napoleon’s abdication. Despite his sudden return to power in 1815, it completed its deliberations in June of that year, just a few days before the Battle of Waterloo and the final end to the Napoleonic Wars. The Congress had been convened following a preliminary agreement arrived at by the Treaty of Chaumont in March 1814. Austria was represented by Prince von Metternich, Prussia by Prince von Hardenburg, and Great Britain by its foreign minister Viscount Castlereagh (replaced later by the Duke of Wellington). The Tsar himself, Alexander I, attended on behalf of Russia, and Louis XVIII, the restored Bourbon monarch, appointed Charles Maurice de Talleyrand to negotiate on behalf of the French. Representatives were also sent from Spain, Portugal and Sweden, and some of the minor European states sent envoys to report back on the proceedings.

xxxxxThe reorganisation of Europe presented a formidable task. The French Revolutionary Wars, followed by the Napoleonic Wars, had destroyed or redefined a great deal of the continent’s political framework, leaving many areas in dispute. This was particularly so in central and eastern Europe, where there was a great deal of disagreement over the boundaries of the German states and the thorny problem created over the repartition of Poland -

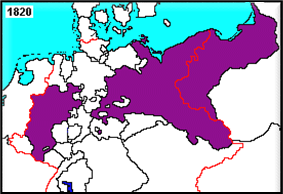

xxxxxIn broad outline the final settlement resulted in the following: The loss of all territory annexed by France since 1792 (agreed earlier at the Peace of Paris); the enlargement of both Prussia and Russia; the formation of a German federation of states; gains by Austria in northern Italy; the restoration of the Papal States and the Kingdom of Piedmont- territories. These terms, considered now in greater detail, were to have a marked impact on the history of Europe for years to come. (MAP BELOW).

territories. These terms, considered now in greater detail, were to have a marked impact on the history of Europe for years to come. (MAP BELOW).

xxxxxFrance had to accept the return of the Bourbon monarchy (Louis XVIII), and the country lost all territories annexed from 1792 to 1810 -

xxxxxPrussia retained the Polish territory gained in the previous partitions, together with the province of Posen and the cities of Danzig and Thorn. The Grand Duchy of Berg was acquired from Germany, together with territory from Saxony (about two fifths) and the Dutchy of Westphalia. Furthermore, Prussia was also ceded Swedish Pomerania and the Rhine Province, the latter at the insistence of Castlereagh, who was anxious to provide a bulwark against France and the new kingdom of the Netherlands. These acquisitions put Prussia firmly back on the map, but for some time she was overshadowed by Austria, her more powerful neighbour. As we shall see, however, given time and the rise of their formidable leader Otto von Bismarck, this neighbour was to be cut to size in the Austro-

xxxxxPrussia retained the Polish territory gained in the previous partitions, together with the province of Posen and the cities of Danzig and Thorn. The Grand Duchy of Berg was acquired from Germany, together with territory from Saxony (about two fifths) and the Dutchy of Westphalia. Furthermore, Prussia was also ceded Swedish Pomerania and the Rhine Province, the latter at the insistence of Castlereagh, who was anxious to provide a bulwark against France and the new kingdom of the Netherlands. These acquisitions put Prussia firmly back on the map, but for some time she was overshadowed by Austria, her more powerful neighbour. As we shall see, however, given time and the rise of their formidable leader Otto von Bismarck, this neighbour was to be cut to size in the Austro-

xxxxxRussia received the greater part of the Napoleonic Duchy of Warsaw, and retained Finland (taken from Sweden in 1808) and Bessarabia (taken from Turkey in 1812). The area obtained from the Duchy of Warsaw was designated the ”Congress Kingdom of Poland”, but it was placed strictly under the Tsar's sovereignty and incorporated as a separate kingdom under the Russian empire. However, within this area the district of Poznan was given over to Prussia, and Cracow was declared a free city. The Congress thrust Tsar Alexander I into the very front of European politics. He posed as a man with liberal intentions, and his idea of a “Holy Alliance” seemed to confirm that, but he was a reactionary at heart, and his successor Nicholas I, was even more so. And there was, too, the imminent break-

xxxxxThexGerman states (reduced from 300 to 39) were formed into a German Confederation and a Diet was set up under the Presidency of Austria. Each state was to be independent for internal affairs, but war could not be waged between states, and warfare against a foreign state required the sanction of the Confederacy. Hanover was made into a kingdom, and Bavaria acquired territory along the Rhine, including the city of Mainz. The Confederation took some time to gel, but some progress was made in 1834 by the establishment of a customs union, the Zollverein, under Prussian leadership. An attempt at unity failed in 1848 but, as we shall see, the Prussian victories over the Austrians in 1866 (Va) and then the French in 1870, was to lead to the formation of the German Empire, due mainly to the efforts of the Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck.

xxxxxAustria was restored almost to its pre-

xxxxxAustria was restored almost to its pre-

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxItaly remained, in the words of Metternich, “a geographical expression”. Ferdinand I was recognised as the king of Naples and Sicily; the Pope received the Legation of Bologna and the bulk of Ferrara, and Tuscany and Modena were assigned to Habsburg princes. The kingdom of Sardinia was restored and regained Savoy, Nice and Piedmont, as well as Genoa and Liguria. In addition, Parma, Piacenza and Guastella were granted to the Empress Marie Louise (consort of the deposed Napoleon) for her lifetime. But whilst Italy might well be termed a “geographical expression” in 1815, it was also a geographical entity, due to the Alps in the north and the Mediterranean in the south. Secret societies, like the Carbonari, and the open Young Italy movement, founded by the revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini in 1831, sought independence for the peninsula and, as we shall see, took up the armed struggle in earnest in 1848 (Va).

xxxxxThe Low Countries became the Kingdom of the Netherlands, made up of the former United Provinces and the Austrian Netherlands, and placed under the sovereignty of the House of Orange. At the same time the king of the Netherlands was made Grand Duke of Luxembourg and, as such, became a member of the German Confederation. The establishment of this kingdom across the North Sea was important to the British government, but, as foreseen by many, this union of Protestant Dutch and Roman Catholic Belgians had little hope of a stable future. As we shall see, in 1831 (W4) the British foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston (illustrated), was to play a prominent part in negotiating Belgian independence under Leopold I.

xxxxxThe Low Countries became the Kingdom of the Netherlands, made up of the former United Provinces and the Austrian Netherlands, and placed under the sovereignty of the House of Orange. At the same time the king of the Netherlands was made Grand Duke of Luxembourg and, as such, became a member of the German Confederation. The establishment of this kingdom across the North Sea was important to the British government, but, as foreseen by many, this union of Protestant Dutch and Roman Catholic Belgians had little hope of a stable future. As we shall see, in 1831 (W4) the British foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston (illustrated), was to play a prominent part in negotiating Belgian independence under Leopold I.

xxxxxSweden retained Norway (conceded by Denmark at the Peace of Kiel in 1814), but the Norwegians were guaranteed their “liberties and rights”. Pomerania, which had been ceded to Denmark at the Peace of Kiel, was given over to Prussia, but the Danes were compensated by acquiring the Duchy of Lauenburg in northern Germany. The Union between Sweden and Norway was never successful. Norway looked upon it as a union of equal states, whilst Sweden regarded Norway as a conquered territory. As we shall see, after many years of constitutional crises, Norway gained its full independence in 1905.

xxxxxGreat Britain retained the islands of Malta and Heligoland and, in addition received Mauritius, Tobago and Santa Lucia from France, Trinidad from Spain, and Ceylon and the Cape of Good Hope and Dutch Guiana from Holland -

xxxxxSpain saw the return of Ferdinand VII, and lost Trinidad to Britain, and Portugal lost Guiana to France. Switzerland was increased in size from 19 to 22 cantons (Geneva, Wallis and Neuchatel), provided with a new constitution, and recognized as a confederation of independent cantons, its neutrality guaranteed by the Great Powers.

Including:

The Congress System

and the Barbary Pirates

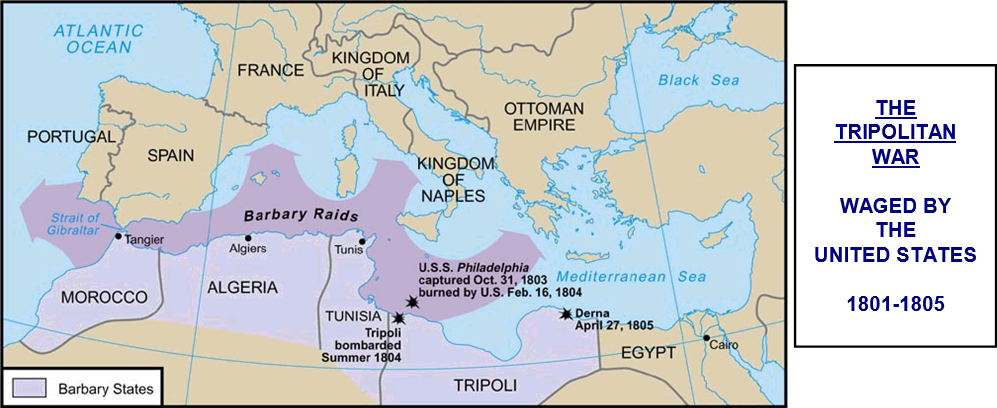

xxxxxWhilst in session, the Congress of Vienna had turned its attention to the Barbary Pirates. As we have seen (1638 C1), by the reign of Murad IV these corsairs, based along the north coast of Africa, had become a considerable danger to shipping and coastal towns. The various groups had combined, and the use of sailing ships in place of galleys had meant that operations could be extended into the Atlantic. Over the years, various countries had attempted to destroy their bases. Then in 1801 to 1805 the United States of America waged a war against Tripoli (The Tripolitan War). This proved effective, but the overall danger remained. In 1815 the British, on behalf of the Congress of Vienna, attempted to reach a settlement. When this failed, in 1816 they joined with the Dutch in bombarding the city of Algiers. A tentative agreement was then reached, but a further bombardment was necessary in 1824, and it was not until 1830, when the French occupied the city, that piracy was totally suppressed. The French made Algeria a colony in 1843, and then became responsible for the protectorates of Tunisia in 1881 and Morocco in 1911. A year later Italy gained control of Libya. By then the Barbary Pirates had long ceased to exist.

xxxxxBy the 1500s the Barbary Pirates, based along the North African coast, had become a serious menace to merchant shipping in the eastern Mediterranean. Emperor Charles V launched an attack upon them in 1535, and the defeat of the Ottoman Turks at the naval Battle of Lepanto in 1571, brought a brief respite, but, as we have seen (1638 C1), by the reign of the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV the various groups had combined forces and, by using sailing boats instead of galleys, had increased their activities and extended their operations into the Atlantic. Raids were made upon towns along the southern coasts of Ireland and England in order to capture slaves, for example, and shipping was attacked as far south as the Canary Islands and as far north as Iceland. The Barbary States became so powerful that many European states paid indemnities to their rulers to save their shipping from attack, though such agreements were not always honoured. Over the years numerous attacks were launched against the pirates’ strongholds, but none was successful in the long term, and the plundering continued throughout the 18th century.

xxxxxInxthe opening years of the 19th century the United States -

xxxxxThe settlement hammered out at the Congress of Vienna was the most extensive and comprehensive that Europe had ever witnessed. It was, to a very large extent, a turning back of the political clock. There was little if any regard for the civil rights and freedoms which had inspired the French Revolution and plunged Europe into turmoil. However, it achieved its primary aim -

xxxxxFurthermore, the Congress of Vienna was something of a water-

xxxxxIncidentally, although representing the vanquished, the French delegate to the Conference, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand (1754-

xxxxxIncidentally, although representing the vanquished, the French delegate to the Conference, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand (1754-

Acknowledgements

Congress: by the French painter Jean Baptiste Isabey (1767-

G3c-