THE FRENCH REVOLUTION 1789 -

LOUIS XVI ATTEMPTS TO ESCAPE -

xxxxxIt was in October 1789 that a Paris mob descended on Versailles and escorted Louis XVI and his family back to Paris. He was now obliged to accept the changes taking place, and in July 1790 he publicly approved the first draft of the new constitution. But politically, this virtually reduced him to a mere figurehead, and he could not accept the humiliation. In June 1791, egged on by his wife, the unpopular Marie Antoinette, the family attempted to leave the country, but they were recognised on the way and arrested at Varennes close to the border with the Austrian Netherlands. Amongst the general public he now lost any support he may have had. He was seen as an émigré, anxious to stamp out the people’s bid for greater freedom. A mass demonstration against him had to be put down by force -

xxxxxAs we have seen, in October 1789 a triumphant mob, mostly made up of women, marched on Versailles and escorted Louis XVI and his family back to Paris. Virtually held a prisoner in the Tuileries Palace, he was now obliged to go along with the feverish and often violent tide of reform which was gripping the country. On the 14th July 1790 at the Festival of the Champs de Mars in Paris -

xxxxxAs we have seen, in October 1789 a triumphant mob, mostly made up of women, marched on Versailles and escorted Louis XVI and his family back to Paris. Virtually held a prisoner in the Tuileries Palace, he was now obliged to go along with the feverish and often violent tide of reform which was gripping the country. On the 14th July 1790 at the Festival of the Champs de Mars in Paris -

xxxxxBut if, in public, he went through the motions, in private he stubbornly opposed the new constitution, and was horrified at the frightening turn of events. Under the new form of government, his role as monarch was purely decorative. He had executive authority but under strict limitations. His veto power could only be used to suspend action, and the conduct of foreign affairs was virtually in the hands of the Assembly. He could not face such a prospect. Furthermore, the antagonism towards him and his family was clearly demonstrated at Eastertide in 1791, when he and his family set out to attend a service at St. Clouds and were turned back by an angry mob. This only added to his resolve. He decided to flee the country and seek aid from fellow monarchs. Thisxidea was supported, indeed planned, by his Austrian wife Marie Antoinette (illustrated), a frivolous, indiscreet woman who was already hated and mistrusted by the common people.

xxxxxBut if, in public, he went through the motions, in private he stubbornly opposed the new constitution, and was horrified at the frightening turn of events. Under the new form of government, his role as monarch was purely decorative. He had executive authority but under strict limitations. His veto power could only be used to suspend action, and the conduct of foreign affairs was virtually in the hands of the Assembly. He could not face such a prospect. Furthermore, the antagonism towards him and his family was clearly demonstrated at Eastertide in 1791, when he and his family set out to attend a service at St. Clouds and were turned back by an angry mob. This only added to his resolve. He decided to flee the country and seek aid from fellow monarchs. Thisxidea was supported, indeed planned, by his Austrian wife Marie Antoinette (illustrated), a frivolous, indiscreet woman who was already hated and mistrusted by the common people.

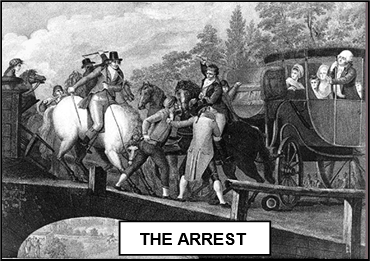

xxxxxThe plan of escape was well thought out. False passports were obtained, the route was chosen in advance, and post horses organised at different points along the way. During the night of the 20th June 1791, the royal party, heavily disguised, set out for the border with the Austrian Netherlands, but various delays occurred during the journey and the alarm was raised in Paris when they could not be found. Meanwhile, having reached Sante-

xxxxxThe plan of escape was well thought out. False passports were obtained, the route was chosen in advance, and post horses organised at different points along the way. During the night of the 20th June 1791, the royal party, heavily disguised, set out for the border with the Austrian Netherlands, but various delays occurred during the journey and the alarm was raised in Paris when they could not be found. Meanwhile, having reached Sante-

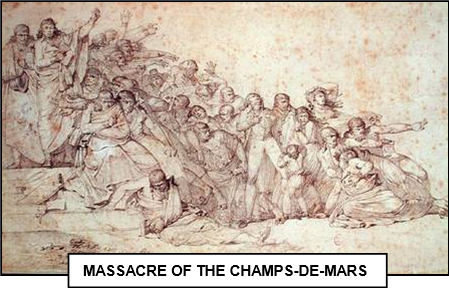

xxxxxFrom that juncture, it can be argued, the Monarchy was doomed. Rashly, before his attempt at escape, he had left behind a letter condemning the revolution, and the constitution he had earlier approved. He now lost the last vestige of the people’s trust, if, indeed, any remained. He was seen as an émigré, an ally of the European monarchs who even then were preparing to stamp out the French people’s bid for freedom. In July, the Cordeliers and the Jacobins, two particularly militant groups of revolutionaries, met outside the Assembly to demand the deposition of the king. This was followed by a mass demonstration, held in the Champs-

xxxxxThe so-

xxxxxThe so-

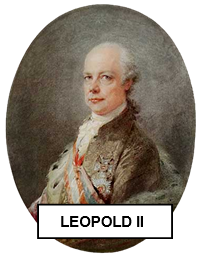

xxxxxThe Legislative Assembly that opened in the October was predominantly radical. The Feuillants did in fact favour a constitutional monarchy, but two larger parties, the Girondists and the Montagnards, were strongly in favour of some form of republic. They feared the growing strength of the émigres gathering along the Rhine, and the plans for intervention that the European monarchs might well be hatching up. Andxtheir fears were partly confirmed in August 1791 when Leopold II, the Archduke of Austria, (goaded it was suspected by his sister Marie Antoinette) met the King of Prussia and, by the Declaration of Pillnitz, delivered a thinly veiled threat against militant democracy. This gave rise to the fear that, among others, the monarchs of Russia, Sweden and Spain might be lurking in the wings. Given this development, the Girondists saw war as the only means of securing the revolution in France and spreading its message of freedom throughout Europe. And meanwhile, those in favour of a limited monarchy were also coming around to the idea of waging a war, if only in the hope that the revolutionary government would be defeated and the king could be restored as the recognised leader.

xxxxxThe Legislative Assembly that opened in the October was predominantly radical. The Feuillants did in fact favour a constitutional monarchy, but two larger parties, the Girondists and the Montagnards, were strongly in favour of some form of republic. They feared the growing strength of the émigres gathering along the Rhine, and the plans for intervention that the European monarchs might well be hatching up. Andxtheir fears were partly confirmed in August 1791 when Leopold II, the Archduke of Austria, (goaded it was suspected by his sister Marie Antoinette) met the King of Prussia and, by the Declaration of Pillnitz, delivered a thinly veiled threat against militant democracy. This gave rise to the fear that, among others, the monarchs of Russia, Sweden and Spain might be lurking in the wings. Given this development, the Girondists saw war as the only means of securing the revolution in France and spreading its message of freedom throughout Europe. And meanwhile, those in favour of a limited monarchy were also coming around to the idea of waging a war, if only in the hope that the revolutionary government would be defeated and the king could be restored as the recognised leader.

xxxxxThus by the end of 1791 power had slipped out of the hands of the moderates and was in the firm grasp of the extremists, and war was on the agenda. As we shall see, in April 1792 the Legislative Assembly declared war on Austria and opened a new phase in the history of the revolt -

xxxxxIncidentally, the public mistrust and hatred of the frivolous Marie Antoinette had been heightened a few years earlier by the so-

Acknowledgements

Marie Antoinette: by the French painter Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-

G3b-