THE ACT OF UNION UNITES GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND 1801 (G3b)

xxxxxThe rebellion of 1798 convinced the British

government that the solution to the Irish problem was to amalgamate

the British and Irish Parliaments, thereby putting an end to

Ireland’s separate institutions. By a combination of bribery and

corruption, the Irish parliament was coerced into voting itself out

of existence, and the Act of Union came into force in January 1801. Once established,

however, George III intervened, and refused to give his consent to

Roman Catholic emancipation, an essential ingredient of the

settlement. Another rising occurred in 1803, but it was not until 1829 (G4), that a movement led

by Daniel O’Connell eventually

gained equal rights for the Roman Catholics. Political unrest and

economic slump continued, however, -

Including:

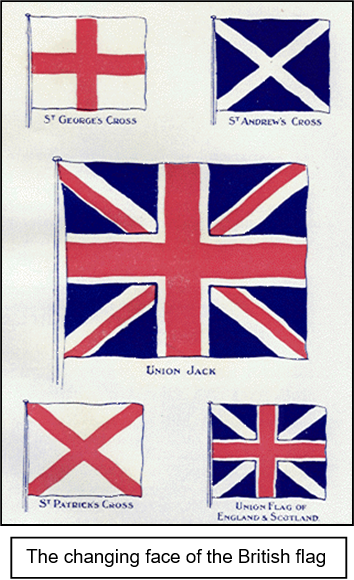

The Union Jack

xxxxxThe Irish

rebellion of 1798,

though failing in its bid for independence, convinced the British

government, led by William Pitt, that a change of policy was needed

towards Ireland. The solution was seen as an amalgamation of the

Irish and British parliaments, thus merging the two kingdoms into

the United Kingdom, and putting an end to

Ireland’s separate political institutions and, hopefully, the

troubles that went with them.

xxxxxThe Irish

rebellion of 1798,

though failing in its bid for independence, convinced the British

government, led by William Pitt, that a change of policy was needed

towards Ireland. The solution was seen as an amalgamation of the

Irish and British parliaments, thus merging the two kingdoms into

the United Kingdom, and putting an end to

Ireland’s separate political institutions and, hopefully, the

troubles that went with them.

xxxxxSuch a dramatic measure was

at once opposed by the Irish parliament but, on the premise (as the

politician Robert Walpole once

said) that “every man has his price”, the British government

persevered. The first bill of union having been rejected early in

1800, it embarked on a broad programme of barely-

xxxxxThe Act of Union of

Britain and Ireland came into effect on the first day of January 1801. By its terms Ireland was to return 100

members to the House of Commons at Westminster, and 32 peers and 4

bishops were to be elected as life-

xxxxxAtxground level the union was

far from popular in Ireland. Indeed, it had hardly been established

when, in July 1803, an uprising against English rule broke out, led

by the Irish patriot Robert Emmet (1778-

xxxxxAtxground level the union was

far from popular in Ireland. Indeed, it had hardly been established

when, in July 1803, an uprising against English rule broke out, led

by the Irish patriot Robert Emmet (1778-

xxxxxAs we shall see, the struggle for religious freedom and full independence (not sought by all) was to be a long one. Catholic Emancipation, led by the dynamic Daniel O’Connell, was not granted until 1829 (G4), and it was not until 1921 that the union was partially disbanded and the Irish Free State was established. Between these two dates, the economy slumped further, and virtually collapsed with the Great Potato Famine of 1845 (Va), and the mass emigration that followed.

Acknowledgement

Emmet:

attributed to the British artist James Petrie (c1745-

G3b-

xxxxxFollowing the union with Ireland in 1801 the Union Jack became the nation’s new flag. This was made up of the red cross of St. George of England, the white cross on a blue background of St. Andrew of Scotland, and the diagonal red cross of St. Patrick of Ireland.

xxxxxFollowingxthe union with

Ireland in 1801, the term United Kingdom became official, and the

Union Jack became the nation’s new flag. The earliest form of the

flag to represent Great Britain, the “Union Flag or “Great Union”

(illustrated on the left), was devised in 1606 soon after James V1 of Scotland

came to the English throne as James I and united the two nations. It

superimposed the red cross of St. George of England upon the white

cross and blue background of the flag of St. Andrew of Scotland.

Because in heraldry red on blue is frowned upon, the red cross of

England was given a white border, in keeping with its own background

colour.

xxxxxFollowingxthe union with

Ireland in 1801, the term United Kingdom became official, and the

Union Jack became the nation’s new flag. The earliest form of the

flag to represent Great Britain, the “Union Flag or “Great Union”

(illustrated on the left), was devised in 1606 soon after James V1 of Scotland

came to the English throne as James I and united the two nations. It

superimposed the red cross of St. George of England upon the white

cross and blue background of the flag of St. Andrew of Scotland.

Because in heraldry red on blue is frowned upon, the red cross of

England was given a white border, in keeping with its own background

colour.

xxxxxDuring the Commonwealth period (1649-

xxxxxDuring the Commonwealth period (1649-