xxxxxThe Fighting

Temeraire of 1838

was the first of a succession of masterpieces produced by Joseph

Turner in the last fifteen years of his life. These included Rockets and Blue Lights of 1840, Snowstorm

at Sea and Burial at Sea of 1842,

Rain, Steam and Speed of 1844, and his

superb paintings of Venice. These vibrant works, remarkable for

their bold colours, free brushwork, and intensity of light, served

to create the atmosphere of a chosen scene, be it a dramatic

incident on land or sea, or a sun-

JOSEPH MALLORD WILLIAM TURNER 1775 -

(G3a, G3b, G3c, G4, W4, Va)

Acknowledgements

Turner: The Fighting Temeraire –

National Gallery, London; The Bridge of Sighs and Ducal Palace,

Venice – Tate Gallery, London; Rain, Steam and Speed – National

Gallery, London; Snowstorm at Sea – Tate Gallery, London. Peace,

Burial at Sea – Tate Gallery, London; Wilkie:

The Penny Wedding – Royal Collection, UK; Self-

xxxxxThe Fighting Temeraire (illustrated) was the first of

a succession of imaginative masterpieces produced in oil and

watercolour by the great English artist Joseph Turner during the

last fifteen years of his life. These brilliant works included The Slave Ship and Rockets

and Blue Lights of 1840, Snow Storm at

Sea and Burial at Sea of 1842, Rain, Steam, and Speed of 1844, and his

superb paintings of Venice -

xxxxxThe Fighting Temeraire (illustrated) was the first of

a succession of imaginative masterpieces produced in oil and

watercolour by the great English artist Joseph Turner during the

last fifteen years of his life. These brilliant works included The Slave Ship and Rockets

and Blue Lights of 1840, Snow Storm at

Sea and Burial at Sea of 1842, Rain, Steam, and Speed of 1844, and his

superb paintings of Venice -

xxxxxAs we have seen (1818 G3c), Turner began his

career in a fairly conventional way. Influenced in particular by the

works of the Englishman Robert Cozens and the Welsh artist Richard

Wilson, he produced romantic landscapes, mythical scenes and

attractive river views, mostly of the Thames. In 1796, however, he

ventured into oil painting with his Fishermen at

Sea, and three years later, having seen works by the French

painter Claude Lorrain -

xxxxxThen in 1819 Turner made his first of two visits to Italy, and was completely won over by the magic quality of the country’s natural light. Fascinated especially by the beauty of Venice, he began painting views of the city and, following his second visit in 1835, introduced original new methods of reproducing the overall effect of light. This technique, together with a bolder use of colour and an even freer use of the brush, produced the masterpieces of his final years.

xxxxxThe first of his great works of the 1830s and 1840s was The Fighting Temeraire, the warship that had distinguished itself in the Battle of Trafalgar. Turner saw it being towed up the Thames on a summer’s evening in 1838, on its way to the breaker’s yard, and quickly made a number of small sketches. The result was a masterpiece which thrilled the public by its patriotic sentiments and marked, by its brilliant use of colour, the passing of the age of sail, pulled to its death by a tug, the symbol of the new age of steam. The warship, graceful, majestic, and bathed in a soft silver light, contrasts vividly with the busy little black tug, belching out fire and smoke against a sky and sea ablaze with the red tones of a setting sun. The English writer William Thackeray likened the scene to the playing of “God save the Queen”.

xxxxxRain, Steam, and Speed (illustrated below), painted in 1844, depicts a steam train of the Great Western Railway as it thunders across a high bridge at the height of a rain storm. We are told that Turner prepared for this painting by sticking his head out of a train window for ten minutes in like weather conditions! The result was a swirling mass of colour which almost engulfs the train itself, blots out all but the barest detail, and conjures up an intense feeling of speed and biting rain.

xxxxxAnd in stark contrast to this turbulent, frenzied

moment-

xxxxxAnd in stark contrast to this turbulent, frenzied

moment-

xxxxxAs one would expect, these

avant-

xxxxxAs a person Turner was

something of a recluse. His gruff manner made him few close friends,

he was mean with money -

xxxxxTurner was one of the

greatest and most prolific of British artists. He worked quickly and

tirelessly throughout his career, and he left over 300 oil

paintings, nearly 20,000 water colours, and some 19,000 sketches,

produced during his life in London, and from his extensive tours of

Britain and the continent. Fascinated by the river life of the

Thames and attracted throughout his career by real-

Including:

John Ruskin

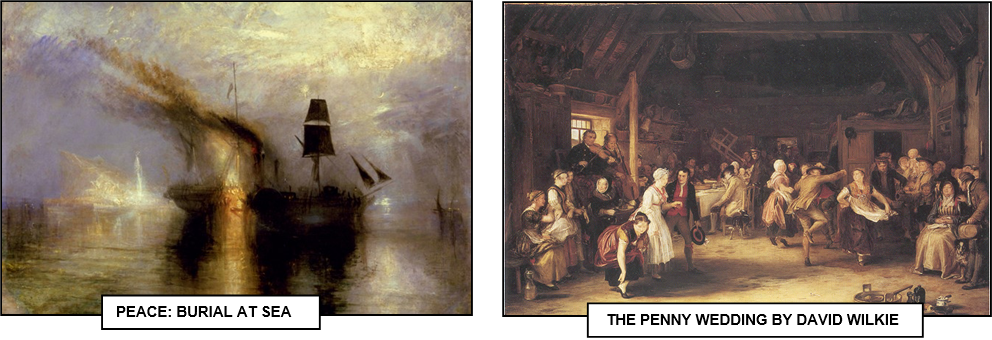

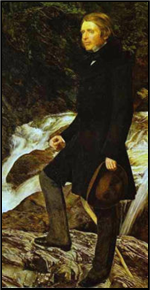

xxxxxIncidentally, Turner painted Peace: Burial

at Sea (illustrated above) to commemorate the death of his close friend and

fellow artist David Wilkie

(1785-

xxxxxIncidentally, Turner painted Peace: Burial

at Sea (illustrated above) to commemorate the death of his close friend and

fellow artist David Wilkie

(1785-

xxxxx…… After Turner’s death his great admirer John Ruskin catalogued his paintings and drawings. Turner bequeathed most of his works to the nation, asking that they be housed in a special gallery. His request was eventually granted. The Clore Gallery, specifically built at the Tate Gallery, London, to house the Turner Collection, was opened in 1987. ……

xxxxx…… An annual prize, named after Turner, was established in 1984 to encourage new developments in contemporary British art. Contestants for the Turner Prize are short listed by a jury, and exhibit their work at the Tate Gallery. The winner receives £20,000.

xxxxx…… When living at Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, Turner had a good view of the Thames, and used to watch the small boats going up and down the river. One such boat was a smack known as a hoy. This carried farm produce and items like coal and salt, but it also acted as a ferry. It is believed that the nautical term “Ahoy” comes from people on the bank calling out for the ferry service. ……

Va-

xxxxxAs we have seen, the English art and social critic John Ruskin (1819-

xxxxxAs we have seen, the English art and social critic John Ruskin (1819-

xxxxxRuskin was born in London,

the only son of John James Ruskin, a prosperous wine merchant. A

precocious, self-

xxxxxIt was his admiration for this well-

xxxxxIt was his admiration for this well-

xxxxxIn 1845 Ruskin began a new phase in his career. In

April of that year he visited northern Italy and, having made

sketches of the Gothic architecture there and been overwhelmed by

its romantic beauty, he decided to put his thoughts on paper. After

a further visit to the area and a journey into northern France in

August 1848, he returned to start work. By April 1849 he had

completed the text and the illustrations for The

Seven Lamps of Architecture. Then, as a sequel, later that

year he and his wife (he had married in 1848) spent the winter in

Venice, and his studies there resulted in the first volume of The Stones of Venice in 1851. These works

established him as a leading authority in architecture, and one with

a theory to prove. Continuing his theme of “truth to nature”, he

argued that, unlike other styles, such as the artificial exuberance

of Baroque, both Gothic and Venetian architecture had been inspired

by genuine religious fervour and, by dint of their moral basis, were

valid forms of art.

xxxxxIn 1845 Ruskin began a new phase in his career. In

April of that year he visited northern Italy and, having made

sketches of the Gothic architecture there and been overwhelmed by

its romantic beauty, he decided to put his thoughts on paper. After

a further visit to the area and a journey into northern France in

August 1848, he returned to start work. By April 1849 he had

completed the text and the illustrations for The

Seven Lamps of Architecture. Then, as a sequel, later that

year he and his wife (he had married in 1848) spent the winter in

Venice, and his studies there resulted in the first volume of The Stones of Venice in 1851. These works

established him as a leading authority in architecture, and one with

a theory to prove. Continuing his theme of “truth to nature”, he

argued that, unlike other styles, such as the artificial exuberance

of Baroque, both Gothic and Venetian architecture had been inspired

by genuine religious fervour and, by dint of their moral basis, were

valid forms of art.

xxxxxIn 1851, as in the case of Turner, Ruskin took up the

cause of the Pre-

xxxxxIn 1851, as in the case of Turner, Ruskin took up the

cause of the Pre-

xxxxxIn support of this idea of

“regeneration” Ruskin lectured widely, taught at a girls’ school in

Cheshire for some years, and wrote a large number of essays. Those

denouncing the economic policy of laissez-

xxxxxIn 1871 his mother died, and he sold up his house in

Denmark Hill and moved to the Lake District to live at Brantwood, a

house overlooking Coniston Water. It was here that he established

his Guild of St. George, a somewhat vague brotherhood designed to

provide money for worthy public projects. The organization was

publicised through his Fors Clavigera (Club of Fate) a series of letters to the

nation’s working men spelling out the ills of contemporary society.

It was one of these letters which contained a vicious attack on a

painting by the American artist James McNeill Whistler and led to a

libel action in 1878. The decision went against Ruskin, and though

the costs awarded were less than a penny, it was a moral defeat, and

virtually brought his career to an end. By then, however, his mental

powers were already in decline. Despite periods of mental

disturbance, he continued to write and lecture for some years, but

in 1889 he became mentally deranged, and remained a total invalid

for the last eleven years of his life.

xxxxxIn 1871 his mother died, and he sold up his house in

Denmark Hill and moved to the Lake District to live at Brantwood, a

house overlooking Coniston Water. It was here that he established

his Guild of St. George, a somewhat vague brotherhood designed to

provide money for worthy public projects. The organization was

publicised through his Fors Clavigera (Club of Fate) a series of letters to the

nation’s working men spelling out the ills of contemporary society.

It was one of these letters which contained a vicious attack on a

painting by the American artist James McNeill Whistler and led to a

libel action in 1878. The decision went against Ruskin, and though

the costs awarded were less than a penny, it was a moral defeat, and

virtually brought his career to an end. By then, however, his mental

powers were already in decline. Despite periods of mental

disturbance, he continued to write and lecture for some years, but

in 1889 he became mentally deranged, and remained a total invalid

for the last eleven years of his life.

xxxxxRuskin achieved a great

deal of success in his chosen career, but his personal life was not

a happy one. A teenage infatuation for a young Spanish girl seems to

have affected him emotionally, and his marriage to Euphemia Gray in

1848 ended in scandal and an annulment six years later. By all

accounts the marriage was never consummated, and she left him for

the artist John Millais when they became involved with the Pre-

xxxxxAs a pioneer in the fields

of art criticism and history, it must be said that Ruskin’s works

were limited in scope, not always well structured, and exploited for

his own artistic theory. Nevertheless, from the 1850s onwards they

had a marked influence upon Victorian public taste, awakening a

wider interest in the arts and playing a vital role in championing

the unorthodox views of Joseph Turner and the Pre-

xxxxxIncidentally, as noted earlier, following the death of Joseph Turner in 1851, Ruskin offered to catalogue the thousands of drawings and paintings which the artist had left to the National Gallery. Starting early in 1857, it took him the best part of a year to complete the task. A great admirer of Turner, he claimed that “his sense of beauty was perfect .. only that of Keats and Tennyson being comparable with it”.

xxxxx……

The fact that the American artist James Whistler sued Ruskin for

libel in 1878 is hardly surprising. In denouncing his Nocturne

in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (illustrated), Ruskin accused him of “ill-

xxxxx…… Ruskin’s last book was a charming but incomplete autobiography entitled Praeterita. He started writing it in 1885, using a diary he had kept from his early years, but was unable to finish it following a particularly severe attack of madness in the summer of 1889. ……

xxxxx…… The portrait of Ruskin above was the work of his friend John Millais. He began it when they were on holiday together in Scotland in 1853. The following year, Ruskin’s wife Effie left him, having fallen in love with Millais, but nevertheless Ruskin insisted that the painting be completed.

xxxxxAs we have seen, the

English art and social critic John Ruskin (1819-