xxxxxWith the resumption of the

war between Britain and France in 1803, Napoleon assembled a

sizeable army at Boulogne. As a consequence, in 1805 Admiral Horatio Nelson was sent to the Mediterranean to blockade the port of

Toulon, where a large French fleet was preparing to assist in an

invasion of England. The French fleet managed to evade the blockade,

and join a Spanish fleet at Cadiz, but when the combined force took

to the high seas in October, the British caught up with it off Cape

Trafalgar on the south-

THE NAPOLEONIC WARS 1803 -

THE BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR -

Acknowledgements

Trafalgar: sketch by the English

painter Clarkson Frederick Stanfield (1793-

xxxxxThe Battle of Trafalgar, one of the most famous naval

engagements in history, took place off the cape of that name in

south-

xxxxxThe Battle of Trafalgar, one of the most famous naval

engagements in history, took place off the cape of that name in

south-

xxxxxNelson, following his successful command at the Battle

of Copenhagen in 1801 (G3b),

returned to England, where the Treaty of Amiens of 1802 had brought

a short period of troubled peace. But he was not long out of action.

When the war broke out again in May 1803, Napoleon assembled a

sizeable army at Boulogne, and Nelson was sent to blockade the

Mediterranean port of Toulon, where a large French fleet was

preparing to assist in the invasion of England. Inx1805,

however, under cover of bad weather, the French fleet, commanded by

Admiral Pierre de Villeneuve,

escaped from Toulon and made for the West Indies. Nelson gave chase,

but Villeneuve evaded him and, turning back to Europe, sailed to

Cadiz. where he was joined by a Spanish fleet. Again the British

attempted a blockade, but this time, under direct orders from

Napoleon to break out and land troops at Naples (to assist the

French campaign there), Villeneuve slipped his combined force out of

Cadiz on the 20th October, hoping to make it safely to the

Mediterranean. On the following day, however, Nelson confronted him

off Cape Trafalgar and battle was joined.

xxxxxNelson, following his successful command at the Battle

of Copenhagen in 1801 (G3b),

returned to England, where the Treaty of Amiens of 1802 had brought

a short period of troubled peace. But he was not long out of action.

When the war broke out again in May 1803, Napoleon assembled a

sizeable army at Boulogne, and Nelson was sent to blockade the

Mediterranean port of Toulon, where a large French fleet was

preparing to assist in the invasion of England. Inx1805,

however, under cover of bad weather, the French fleet, commanded by

Admiral Pierre de Villeneuve,

escaped from Toulon and made for the West Indies. Nelson gave chase,

but Villeneuve evaded him and, turning back to Europe, sailed to

Cadiz. where he was joined by a Spanish fleet. Again the British

attempted a blockade, but this time, under direct orders from

Napoleon to break out and land troops at Naples (to assist the

French campaign there), Villeneuve slipped his combined force out of

Cadiz on the 20th October, hoping to make it safely to the

Mediterranean. On the following day, however, Nelson confronted him

off Cape Trafalgar and battle was joined.

xxxxxThe Franco-

xxxxxThe Franco-

xxxxxThe engagement began about noon and was virtually all over in four hours. By that time the French and Spanish had lost 15 ships sunk, and of the 18 which escaped, two were lost at sea and four were captured early in November. By contrast, the British lost no ships, and their casualties, killed and wounded amounted to about 1,500 compared with some 6,000. In addition, Admiral Villeneuve was captured, along with thousands of his men.

xxxxxA great deal has been

written about Nelson, his naval career and his personal life. Much

of it has been hero worship, some of it has been critical. From the

historical point of view, at least two points are worthy of mention.

Firstly, his tactics as a naval commander, generally unorthodox and

sometimes bordering on the foolhardy, won vital victories for his

nation, and served to determine the course of its history. Secondly,

despite the harsh and cruel aspects of naval life at this time, he

instilled a sense of duty and a spirit of comradeship in all those

under his command. He regarded his ship’s company, and, indeed, his

whole fleet, as a “band of brothers”, united in the service of its

country. This so-

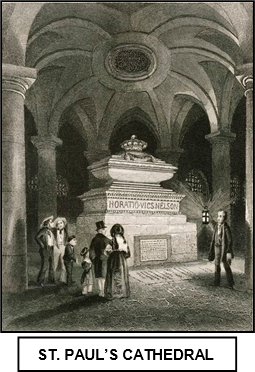

xxxxxIncidentally, Nelson’s body was returned to England, preserved in a barrel of brandy, and a nation in mourning gave its greatest naval commander and tactician a state funeral in St. Paul’s Cathedral. His flagship, The Victory, is preserved at Portsmouth docks in southern England. ……

xxxxx…… The portrait here of his mistress Emma Hamilton was Nelson’s favourite picture of her. He took “My Guardian Angel” with him on all his voyages, and asked for it when he lay dying. ……

xxxxx…… A monument to Lord Nelson,

“Nelson’s Column”, was completed in Trafalgar Square, London, in

1843. It is 170ft high and surmounted by a 18ft statue of the naval

commander, the work of the sculptor Edward

Hodges Baily (1788-

xxxxx…… A monument to Lord Nelson,

“Nelson’s Column”, was completed in Trafalgar Square, London, in

1843. It is 170ft high and surmounted by a 18ft statue of the naval

commander, the work of the sculptor Edward

Hodges Baily (1788-

xxxxx…… One version of Nelson’s coat of arms shows a British sailor trampling on the Spanish flag (on the left) and the British lion tearing it apart (on the right). ……

xxxxx…… The

bullet that killed Nelson is on display in Windsor Castle, and his

uniform -

xxxxx……

In May 2002 Colin White, an historian working for the National

Maritime Museum at Greenwich, came across a battle plan while

looking through the museum’s archives. After careful inspection, it

is now believed that these scrawled pen lines on a scrap of

yellowing paper (illustrated)

were made by Nelson himself, just before the Battle of Trafalgar.

Certainly the lower part of the diagram shows two divisions of the

British fleet advancing from the left and cutting through the

enemy’s line at right angles. If the plan was drawn up by Nelson -

Including:

Horatio Nelson

and John Flaxman

xxxxxNelson’s funeral monument in St. Paul’s Cathedral (illustrated below) was the work

of the English sculptor John Flaxman (1755-

xxxxxNelson’s funeral monument in St. Paul’s Cathedral (illustrated below) was the work

of the English sculptor John Flaxman (1755-

xxxxxFlaxman was born in York, and in 1770 began studying at the Royal Academy Schools in London, where he showed marked promise. As we have seen, early in his career he worked with Josiah Wedgwood (1760 G3a), and many of the fine antique designs which made Wedgwood pottery so famous were of his making. He it was who provided the vast variety of delicate relief figures and medallions, the majority of them based on Greek or Roman models.

xxxxxHe started working for Wedgwood in 1755, and in 1787 was appointed director of the company’s studio in Rome. He held this office until 1794 and, during this time made a close study of classical art, the works of the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova, and the writings of the German art historian Johann Winckelmann. To this period belongs the publication of his exquisite line drawings for the Iliad and Odyssey, Homer’s ancient epics, and several marble statues, including The Fury of Athamas from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

xxxxxOn his return to London in 1794 he continued his book

illustrations, providing drawings for works by the ancient Greek

dramatist Aeschylus, and for Dante’s Divine

Comedy, but he also began to specialise as a monumental

sculptor. His monument to the Earl of Mansfield in Westminster

Abbey, completed in 1801, secured his reputation in this field. He

became a full member of the Royal Academy in

xxxxxOn his return to London in 1794 he continued his book

illustrations, providing drawings for works by the ancient Greek

dramatist Aeschylus, and for Dante’s Divine

Comedy, but he also began to specialise as a monumental

sculptor. His monument to the Earl of Mansfield in Westminster

Abbey, completed in 1801, secured his reputation in this field. He

became a full member of the Royal Academy in  1800,

and was appointed its first professor of sculpture ten years later.

During this period he received and fulfilled a large number of

commissions. In addition to the Nelson monument and those for Joshua

Reynolds and Robert Burns, for example, he sculpted monuments for

Captain James Montague in Westminster Abbey and the figure of

Apollo in Petworth House, Sussex (illustrated

here).

1800,

and was appointed its first professor of sculpture ten years later.

During this period he received and fulfilled a large number of

commissions. In addition to the Nelson monument and those for Joshua

Reynolds and Robert Burns, for example, he sculpted monuments for

Captain James Montague in Westminster Abbey and the figure of

Apollo in Petworth House, Sussex (illustrated

here).

xxxxxA life-

xxxxxIncidentally,

another English sculptor at this time who deserves a mention is Francis Chantrey (1781-

xxxxxIncidentally,

another English sculptor at this time who deserves a mention is Francis Chantrey (1781-

xxxxxNelson’s

funeral monument in St. Paul’s Cathedral was the work of the English

sculptor John Flaxman

(1755-

G3c-