xxxxxThe English politician Viscount Charles Townshend served both George I and George II as secretary of state for foreign affairs, but in 1730, following a power struggle with Robert Walpole, he was forced to resign. Today he is best remembered as "Turnip Townshend" because of the various improvements he made in farming methods while managing his estate at Rainham in West Norfolk.

VISCOUNT “TURNIP TOWNSHEND” 1674 - 1738

(C2, J2, W3, AN, G1, G2)

Acknowledgements

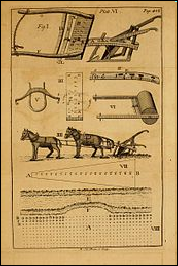

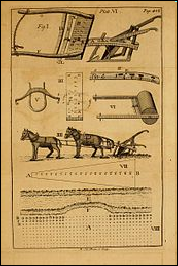

Reaper: date and artist unknown. Townshend: detail, after the German/British portrait painter Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723), c1715/20 – National Portrait Gallery, London. Husbandry: illustration of a plough from Tull’s The New Horse and Hoeing Husbandry, first published in 1731, artist unknown. Cornfield: by the Dutch Post-impressionist painter Van Gogh (1853-1890).

G2-1727-1760-G2-1727-1760-G2-1727-1760-G2-1727-1760-G2-1727-1760-G2-1727-1760-G2

xxxxxBy this reign, the Agricultural Revolution, started a good century earlier, was well under way, driven on by a rapidly expanding population. Recovery in farming was slow after the disasters of the 14th century - famine, floods, the Black Death, and The Hundred Years' War - and, as a result, many farmers turned to sheep and cattle raising, and the production of fodder crops, like the turnip. This meant that much open land became "enclosed". The invention of improved farming equipment - such as the "Rotherham plow" and the horse-drawn drill invented by Jethro Tull in 1701 (W3) - increased production, as did the publication in 1731 of Tull's book The New Horse and Hoeing Husbandry. Meanwhile, experiments in crop rotation led to the four-course system, quite common in England by 1800, and quickly adopted on the continent. Science also played a part in both arable farming and stock breeding - to be seen in the work of the English scientist Humphry Davy (1815 G3c) - as did the founding of a number of agricultural colleges and societies. As time went by, the increase in city populations due to the Industrial Revolution further increased the demand for food, and this was met in the main by the growing of cereal crops in eastern Europe, and an ever increasing supply of food from the New World.

xxxxxImprovements introduced by Viscount Townshend were but part of an Agricultural Revolution which had started a good century earlier and, because of a rapidly expanding population, was quickly gathering pace. As we have seen, events of the 14th century seriously affected agriculture throughout Europe. Three consecutive years of extremely bad weather (1314-15) brought severe famine and floods, and the Black Death which broke out in 1347 killed around one third of Europe's population. This, together with the ravages of The Hundred Years' War, brought agriculture to a standstill over vast areas. Because of the lack of labourers, much of the arable land could not be cultivated, and many villages became deserted.

xxxxxImprovements introduced by Viscount Townshend were but part of an Agricultural Revolution which had started a good century earlier and, because of a rapidly expanding population, was quickly gathering pace. As we have seen, events of the 14th century seriously affected agriculture throughout Europe. Three consecutive years of extremely bad weather (1314-15) brought severe famine and floods, and the Black Death which broke out in 1347 killed around one third of Europe's population. This, together with the ravages of The Hundred Years' War, brought agriculture to a standstill over vast areas. Because of the lack of labourers, much of the arable land could not be cultivated, and many villages became deserted.

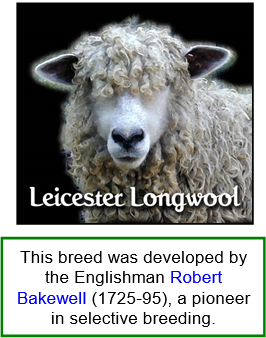

xxxxxRecovery was slow, particularly on the continent where a series of wars continued to devastate vast tracts of farm land. Partly for this reason, in the 16th century, farmers turned to sheep and cattle raising, and the production of fodder crops. This in turn led to the enclosure movement - notably in England and Germany - wherein strip cultivation and the common land of the manorial system were "enclosed" to provide individual holdings for grazing livestock. It is estimated that in England some six million acres were enclosed between 1700 and 1845. As part of this movement, towards the end of the 17th century the turnip began to be used as a major fodder crop. This not only improved the quality of the animals themselves, but also the manure they produced, thus adding better nutriment to the soil on which they grazed.

xxxxxThese changes were intensified by the invention of improved farming equipment. As we have seen, for example, in 1701 (W3) the Englishman Jethro Tull, working on his father's farm in Oxfordshire, invented the horse-drawn drill, a machine which revolutionised the process of sowing (illustrated). He followed this up during the present reign with the publication of his The New Horse and Hoeing Husbandry in 1731, a work which advised on the use of manure and fertilisers, and stressed the importance of "pulverising" the soil. Also of this period was the "Rotherham plow". Probably of Dutch origin and varying in design, it was mainly used in the Netherlands and parts of England and Scotland and greatly improved the process of tillage. But, generally conservative by nature, many farmers were slow to adopt new methods, either through lack of funds or a reluctance to change.

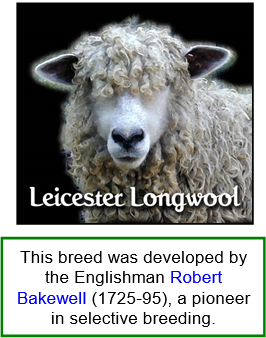

xxxxxMeanwhile, experiments in the rotation of crops - in which Townshend and others played a part - eventually led to the four course system - wheat in the first year, turnips in the second, barley in the third, and clover and ryegrass in the fourth for feed or grazing. In England, this system was in fairly general use by 1800, and was increasingly adopted on the continent during the new century. Alongside these improvements went a growing scientific interest in arable farming and stock breeding, and the need for education in such matters. Frederick William I of Germany founded an agricultural college at Halle as early as 1727, and a society specialising in agriculture was established at Zurich in 1747. Many other such institutions, together with public bodies, followed over the next fifty years, together with the opening of a number of veterinary schools on the continent and in England.

xxxxxAnd such Improvements were becoming increasingly urgent. The Industrial Revolution was beginning to move into first gear and by the end of the 18th century the demand for food in the new industrial centres was fast outstripping local production. This stimulated the growing of cereal crops in eastern Europe, especially in Poland and parts of Russia. And the New World also began to play an increasing role. Some tropical imports were already supplementing the food supply - such as various fruits and coffee, tea and cocoa. Meanwhile, the potato became the staple food in Ireland, and in parts of England and the continent; corn was widely adopted in southern Europe; and the turkey was introduced from South America. And in the offing, too, but still some way off, was the export of cattle and the vast improvements to be brought about by mechanisation. And working alongside these developments was the part to be played by scientific research, as we shall see in the writing and lectures published by the English chemist Humphry Davy on agricultural chemistry (1815 G3c).

xxxxxAnd such Improvements were becoming increasingly urgent. The Industrial Revolution was beginning to move into first gear and by the end of the 18th century the demand for food in the new industrial centres was fast outstripping local production. This stimulated the growing of cereal crops in eastern Europe, especially in Poland and parts of Russia. And the New World also began to play an increasing role. Some tropical imports were already supplementing the food supply - such as various fruits and coffee, tea and cocoa. Meanwhile, the potato became the staple food in Ireland, and in parts of England and the continent; corn was widely adopted in southern Europe; and the turkey was introduced from South America. And in the offing, too, but still some way off, was the export of cattle and the vast improvements to be brought about by mechanisation. And working alongside these developments was the part to be played by scientific research, as we shall see in the writing and lectures published by the English chemist Humphry Davy on agricultural chemistry (1815 G3c).

Including:

The xxxxxxx Agricultural x Revolution

xxxxxViscount Charles Townshend was a prominent Whig politician. He served as secretary of state for foreign affairs under George I, but in 1716 was dismissed for opposing a foreign policy which, as he saw it, put the interests of Hanover above those of Britain. For a time, together with his brother-in-law, Robert Walpole, he lent his support to the king's son, George, Prince of Wales, then in bitter conflict with his father. Later, he served as secretary of state for foreign affairs under George II until forced to resign in 1730 following a power struggle with Walpole.

xxxxxViscount Charles Townshend was a prominent Whig politician. He served as secretary of state for foreign affairs under George I, but in 1716 was dismissed for opposing a foreign policy which, as he saw it, put the interests of Hanover above those of Britain. For a time, together with his brother-in-law, Robert Walpole, he lent his support to the king's son, George, Prince of Wales, then in bitter conflict with his father. Later, he served as secretary of state for foreign affairs under George II until forced to resign in 1730 following a power struggle with Walpole.

xxxxxAlthough an able minister and a leading member of the Whig administration, he is best remembered today as "Turnip Townshend", due to the improvements he made in farming methods on his estate at Rainham, West Norfolk. By experimenting with crop rotation during his eight years of retirement, he substantially increased the quality and quantity of both his fodder and food crops.

xxxxxImprovements introduced by Viscount Townshend were but part of an Agricultural Revolution which had started a good century earlier and, because of a rapidly expanding population, was quickly gathering pace. As we have seen, events of the 14th century seriously affected agriculture throughout Europe. Three consecutive years of extremely bad weather (1314-

xxxxxImprovements introduced by Viscount Townshend were but part of an Agricultural Revolution which had started a good century earlier and, because of a rapidly expanding population, was quickly gathering pace. As we have seen, events of the 14th century seriously affected agriculture throughout Europe. Three consecutive years of extremely bad weather (1314-

xxxxxAnd such Improvements were becoming increasingly urgent. The Industrial Revolution was beginning to move into first gear and by the end of the 18th century the demand for food in the new industrial centres was fast outstripping local production. This stimulated the growing of cereal crops in eastern Europe, especially in Poland and parts of Russia. And the New World also began to play an increasing role. Some tropical imports were already supplementing the food supply -

xxxxxAnd such Improvements were becoming increasingly urgent. The Industrial Revolution was beginning to move into first gear and by the end of the 18th century the demand for food in the new industrial centres was fast outstripping local production. This stimulated the growing of cereal crops in eastern Europe, especially in Poland and parts of Russia. And the New World also began to play an increasing role. Some tropical imports were already supplementing the food supply -

xxxxxViscount Charles Townshend was a prominent Whig politician. He served as secretary of state for foreign affairs under George I, but in 1716 was dismissed for opposing a foreign policy which, as he saw it, put the interests of Hanover above those of Britain. For a time, together with his brother-

xxxxxViscount Charles Townshend was a prominent Whig politician. He served as secretary of state for foreign affairs under George I, but in 1716 was dismissed for opposing a foreign policy which, as he saw it, put the interests of Hanover above those of Britain. For a time, together with his brother-