THOMAS TELFORD 1757 -

(G2, G3a, G3b, G3c, G4, W4)

xxxxxThe Scottish civil engineer Thomas Telford began work as a stonemason, but, after working in Edinburgh, London and Portsmouth, acquired a remarkable understanding of civil engineering. During a long career he constructed roads, bridges and canals throughout Great Britain. He is particularly remembered for his building of the Caledonian Canal in Scotland. This waterway, begun in 1803, required the construction of 23 miles of canal, and was in use by 1822. But his greatest single accomplishment was the suspension bridge over the Menai Straits in north Wales, begun in 1819. When completed in 1826 it was the world’s longest bridge, spanning a distance of 580 ft. In his road-

xxxxxThe Scotsman Thomas Telford, the son of a shepherd, was born in Westerkirk, Dumfries, and began work as an apprentice to a stonemason. He worked for a time in Edinburgh and then, at the age of 25, moved to London. Here, under the direction of the architect William Chambers, he assisted in building extensions to Somerset House. Two years later he found employment in Portsmouth dockyard and, by this time, being both ambitious and hard working, he had virtually taught himself civic engineering. There followed a long and distinguished career during which he gained a worldwide reputation for his construction of roads, bridges, and canals. In recognition of his achievements, he was appointed the first president of the British Institution of Civil Engineers when it was founded in 1818.

xxxxxThe Scotsman Thomas Telford, the son of a shepherd, was born in Westerkirk, Dumfries, and began work as an apprentice to a stonemason. He worked for a time in Edinburgh and then, at the age of 25, moved to London. Here, under the direction of the architect William Chambers, he assisted in building extensions to Somerset House. Two years later he found employment in Portsmouth dockyard and, by this time, being both ambitious and hard working, he had virtually taught himself civic engineering. There followed a long and distinguished career during which he gained a worldwide reputation for his construction of roads, bridges, and canals. In recognition of his achievements, he was appointed the first president of the British Institution of Civil Engineers when it was founded in 1818.

xxxxxHis first major appointment, taken up in 1786, was as the official surveyor for the County of Shropshire. It was while there that he built three bridges over the River Severn, the one at Buildwas being made of cast iron. Then, as engineer to the Ellesmere Canal Company from 1793, he built impressive aqueducts over the Ceirog and Dee valleys in Wales, using for the first time large troughs made up of cast- and Dundee, he built some 900 miles of roadway -

and Dundee, he built some 900 miles of roadway -

xxxxxBut his biggest challenge in Scotland was his overall responsibility for the building of the Caledonian Canal, begun in 1803. This waterway, surveyed by James Watt, and running entirely across northern Scotland from the south west to the north east, was opened in 1822, though it was not finally completed until 1847. Over 60 miles long, it required the making of 23 miles of canal to link up a chain of lochs which included Lochy, Oich and Ness. Until it became too narrow to take the size of modern vessels, this canal, linking as it does the North Atlantic with the North Sea, was extensively used, and proved of great commercial importance.

xxxxxBut his biggest challenge in Scotland was his overall responsibility for the building of the Caledonian Canal, begun in 1803. This waterway, surveyed by James Watt, and running entirely across northern Scotland from the south west to the north east, was opened in 1822, though it was not finally completed until 1847. Over 60 miles long, it required the making of 23 miles of canal to link up a chain of lochs which included Lochy, Oich and Ness. Until it became too narrow to take the size of modern vessels, this canal, linking as it does the North Atlantic with the North Sea, was extensively used, and proved of great commercial importance.

xxxxxBut Telford’s greatest single achievement was the designing and building of the suspension bridge over the Menai Straits, thereby connecting the island of Anglesey with the Welsh mainland at Bangor. He began this work in 1819 after completing a road improvement scheme from Shrewsbury to  Holyhead. The two-

Holyhead. The two-

xxxxxAmong his many other works was a new tunnel for the Trent and Mersey Canal at Harecastle, Staffordshire, a new canal from Wolverhampton to Nantwich, and the St. Katharine Docks in London. And in the summer of 1808 he worked in Sweden, advising on the building of the Gota Canal.

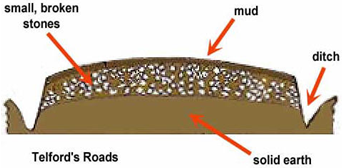

xxxxxYet another of Telford’s notable contributions to Britain’s transport system, and in many ways the most significant, was the marked improvements he introduced in road-

xxxxxYet another of Telford’s notable contributions to Britain’s transport system, and in many ways the most significant, was the marked improvements he introduced in road-

xxxxxIncidentally, Telford’s basic design in road-

xxxxx…… Likewise Telford’s bridge structure was somewhat modelled on that of the first bridge to be built of iron, Coalbrookdale Bridge, constructed in 1779 by Abraham Darby. In 1795 during severe flooding, this bridge was the only one in the area to survive because it had no stone pillars and the flood waters simply flowed through it. This fact did not go unnoticed by Telford. ……

xxxxx…… And one famous suspension bridge that Telford did not design was that which today spans the Avon Gorge at Clifton near Bristol. He submitted a design for it but, as we shall see, it was the one put forward by the great engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel which was adopted in preference. However, in 1963 the new town of Telford, built in Shropshire, England, some 20 miles north-

Acknowledgements

Telford: by the Welsh engraver William Camden Edwards (1777-

Including:

John Loudon

McAdam

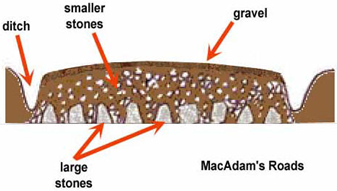

xxxxxAnother Scottish engineer who did pioneer work in road building at this time was John Loudon McAdam (1756-

xxxxxAnother great road builder at this time was the Scottish engineer John Loudon McAdam (1756-

xxxxxAnother great road builder at this time was the Scottish engineer John Loudon McAdam (1756-

xxxxxHowever, with the coming of the motor age, rubber tyres loosened the small stones, and other means had to be found, such as hot tar or asphalt cement, to seal the surface (hence the name “tarmac”). And at a later date the sheer weight of vehicles using the roads required a foundation more in keeping with Telford’s more demanding technique.

xxxxxHowever, with the coming of the motor age, rubber tyres loosened the small stones, and other means had to be found, such as hot tar or asphalt cement, to seal the surface (hence the name “tarmac”). And at a later date the sheer weight of vehicles using the roads required a foundation more in keeping with Telford’s more demanding technique.

xxxxxMcAdam was born in Ayr. He emigrated to the United States at the age of fourteen, and made a fortune working for his uncle, a merchant in New York. He returned to Scotland thirteen years later and, taking an interest in road construction, carried out a series of experiments at his own expense. He was appointed highway commissioner for Bristol in 1806 and, such was his success, that four years later he was made surveyor-

xxxxxIncidentally, a road builder extraordinaire was the Englishman John Metcalf, who died in 1810. Blind from the age of six -

xxxxxIncidentally, a road builder extraordinaire was the Englishman John Metcalf, who died in 1810. Blind from the age of six -

G3c-