xxxxxThe idea of building a canal in Egypt was by no means new. An irrigation channel from the Nile Delta to the Red Sea had been built as early as the 19th century BC, and expanded by the Egyptians and Romans. It was abandoned, however, in 775, and it was the Venetians in the 15th century -

WORK BEGINS ON THE SUEZ CANAL 1859 (Va)

Acknowledgements

Map (Egypt): from www.worldtrek.org/odyssey. Map (Suez Canal): declared to be in the public domain – commons wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Suez+Canal. Drawing from The Young Person’s Cyclopedia of Persons and Places.

Map (The World): licensed under Creative Commons – mrshealyhistoryclass.wikispaces.com.

xxxxxThe idea of building a canal to join the Mediterranean and Red Seas was by no means the first attempt at building an artificial waterway in Egypt. It would seem that as early as the 19th century BC an irrigation channel, navigable at times, was built linking the Nile River to the Red Sea, and this was widened by Ptolemy II during his reign (285 to 246 BC). The Romans extended this waterway and, during the rule of the Roman Emperor Trajan (98-

xxxxxThe idea of building a canal to join the Mediterranean and Red Seas was by no means the first attempt at building an artificial waterway in Egypt. It would seem that as early as the 19th century BC an irrigation channel, navigable at times, was built linking the Nile River to the Red Sea, and this was widened by Ptolemy II during his reign (285 to 246 BC). The Romans extended this waterway and, during the rule of the Roman Emperor Trajan (98-

xxxxxBut these early attempts had been made simply to assist trade from the Nile Delta to the Red Sea. It was the Venetians who, at the close of 15th century, were among the first to suggest the possibility of making a canal through the isthmus itself, linking the two seas. Their trade had been badly affected by the opening of the Cape route to India, and they sought a shorter route to the Far East which worked to their advantage. They began negotiations with the Egyptians, but the Turkish conquest of Egypt in 1517 put an end to their scheme. But the idea did not go away. As we have seen, the German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz suggested the idea of a maritime canal across the isthmus to Louis XIV. Nothing came of it, but interest in the proposal was very much awakened in 1798 following Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion and occupation of Egypt. He ordered a feasibility study, but the project was abandoned when the French survey team concluded -

xxxxxThis miscalculation on the part of the French set the project back by close on half a century. It was not until 1846, in fact, that further surveys were made by a French society interested in the project and it was confirmed that no locks would be required. The society’s scheme never materialised, but it was at this stage that the French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps appeared on the scene. Captivated by Napoleon’s dream of such a canal, he had already made plans as to how it could be built. In reality, he saw little or no prospect of these plans ever leaving the drawing board, but in 1854 fate took a hand. In that year Prince Said of Egypt, whom de Lesseps had known well while serving as a diplomat in Cairo, came to the throne of Egypt. In a matter of months the two friends had agreed to build the canal. In 1858 the Universal Company of the Maritime Suez Canal was given the right to construct and operate the canal, but with the proviso that, after 99 years of operation, ownership would revert to the Egyptian government. The design of the canal and the supervision of its construction was to be in the hands of the French promoter Ferdinand de Lesseps.

xxxxxThis miscalculation on the part of the French set the project back by close on half a century. It was not until 1846, in fact, that further surveys were made by a French society interested in the project and it was confirmed that no locks would be required. The society’s scheme never materialised, but it was at this stage that the French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps appeared on the scene. Captivated by Napoleon’s dream of such a canal, he had already made plans as to how it could be built. In reality, he saw little or no prospect of these plans ever leaving the drawing board, but in 1854 fate took a hand. In that year Prince Said of Egypt, whom de Lesseps had known well while serving as a diplomat in Cairo, came to the throne of Egypt. In a matter of months the two friends had agreed to build the canal. In 1858 the Universal Company of the Maritime Suez Canal was given the right to construct and operate the canal, but with the proviso that, after 99 years of operation, ownership would revert to the Egyptian government. The design of the canal and the supervision of its construction was to be in the hands of the French promoter Ferdinand de Lesseps.

xxxxxDe Lesseps was anxious that the joint stock company should be truly international, but there were few takers. France and the Ottoman Empire ended up with 96% of the shares, and many counties, including Britain, Russia, Austria and the United States, showed no interest at all. Indeed, Britain, openly opposed the scheme, fearing that it would increase French influence in world trade. Lord Palmerston let it be known that his government considered that the canal was a physical impossibility, and the Scottish engineer Robert Stephenson declared the scheme quite impracticable. He and the British government were to change their mind once the canal was up and running!

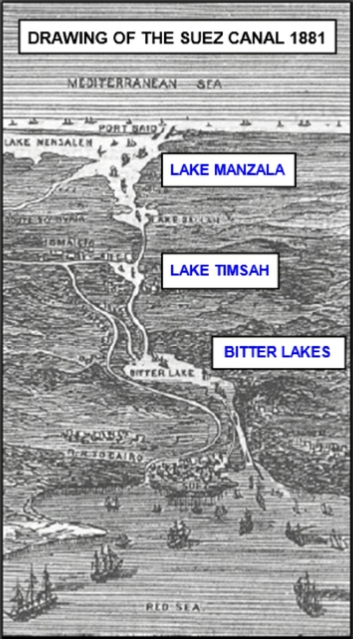

xxxxxThe artificial waterway, just over 100 miles long and located at the crossroads of Europe, Africa and Asia, was planned to run from Port Said on the Mediterranean Sea to the Gulf of Suez in the south, thereby avoiding the journey around the Cape of Good Hope and cutting the distance from London to Bombay, for example, by no less than 42 per cent. The route followed a straight line, using three bodies of water, Lake Manzala, Lake Timsah and the Bitter Lakes (see map above), and, apart from the lakes, several passing bays were provided. The low lying Nile delta was situated to the west and a higher, desert area -

xxxxxThe work on the canal began in April 1859, with the first spadeful of sand removed near the site of Port Said. Some 20,000 labourers were employed, but progress was not rapid, and it took four more years to complete than envisaged, work being slowed down by the soft nature of the terrain, the harsh climate, and a cholera epidemic in 1865. At first, the digging was done by picks and shovels, and the sand or fine earth taken away in baskets -

xxxxxThe canal was opened to shipping in November 1869 (Vb), marked by an elaborate ceremony at Port Said. The cost of completing this monumental project was more than double the original estimate, and the company struggled to survive in the first few years. However, its international value was eventually appreciated, even by the British. In 1875 when money troubles forced the Khedive of Egypt to sell his shares, prime minister Benjamin Disraeli was quick to snap them up on behalf of the British government and thus gain a controlling interest in the Suez Canal. From then onwards Britain was to play an important role in Egypt and its vital short-

Va-