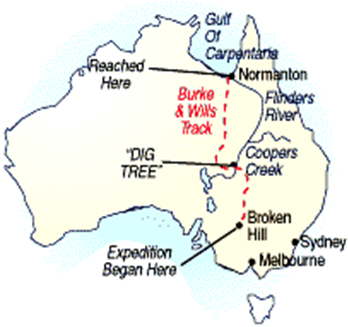

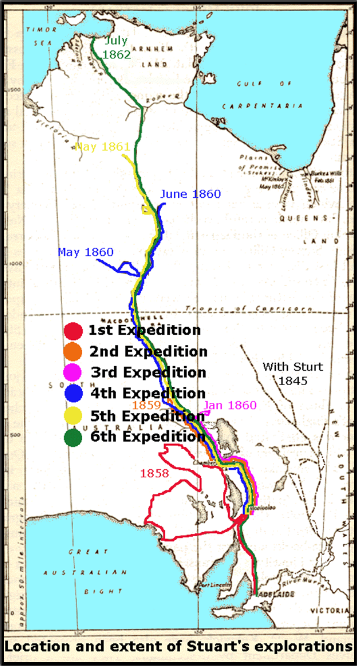

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Scottish-born explorer John McDouall Stuart (1815-1866) gained a great deal of experience as a member of Charles Sturt’s unsuccessful expedition to reach the centre point of Australia in 1846. In 1858 he himself began a series of expeditions into the continent’s interior. He explored the area north of Adelaide, and then in 1860 managed to reach the centre point of Australia. Undaunted by the hardships suffered in these ventures, he then set out to cross the country from Adelaide to Darwin and, after two unsuccessful attempts, reached the north coast in July 1862. But he returned to Adelaide a very sick man, and was forced to return to Scotland. He died in London in 1866. Stuart’s crossing of the continent was a victory for his courage and determination, but he was not the first to achieve this feat. This honour went to his two rivals, Robert O’Hara Burke and William John Wills. They reached the Gulf of Carpentaria in February 1861 but, unlike Stuart, they failed to make the return journey.

JOHN McDOUALL STUART REACHES THE CENTRE OF AUSTRALIA 1860 (Va)

Acknowledgements

Map (Central Australia): source unknown. Stuart: date and artist unknown – John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, South Brisbane. Mount Stuart: contained in Stuart’s Journals 1858-1862 - John McDouall Stuart Society, Adelaide Masonic Centre, South Australia. Burke: wood engraving contained in The London Illustrated News, February 1862, artist unknown – National Library of Australia, Canberra. Wills: wood engraving contained in The London IIlustrated News – National Library of Australia, Canberra. Map (Australia): from https://skippystory.wordpress.com. Death: by the Australian painter John Longstaff (1861-1941), 1907 – National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia.

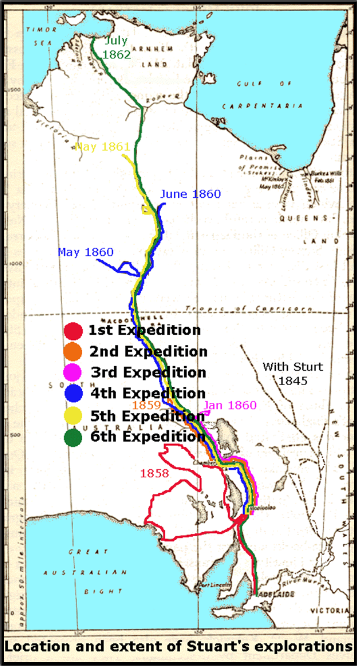

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Scottish-born explorer John McDouall Stuart (1815-1866) accompanied Charles Sturt in his attempt to reach the centre of Australia in 1846. He was engaged as a draughtsman but, on the death of the second-in-command from scurvy, he was appointed in his place. Because of the intense heat and the lack of water due to the unexpected desert terrain, the attempt had to be abandoned and the men were lucky to make it back to Adelaide. However, some years later, in the course of six expeditions between 1858 and 1862, Stuart succeeded where Sturt had failed. Furthermore, in 1862 he managed to hack his way through the jungle of the Northern Territory and reach Van Diemen Gulf on the Indian Ocean, just east of Port Darwin. He almost lost his life on the return journey but, by reaching Adelaide, he became the first man to travel south to north across Australia and survive the journey back.

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Scottish-born explorer John McDouall Stuart (1815-1866) accompanied Charles Sturt in his attempt to reach the centre of Australia in 1846. He was engaged as a draughtsman but, on the death of the second-in-command from scurvy, he was appointed in his place. Because of the intense heat and the lack of water due to the unexpected desert terrain, the attempt had to be abandoned and the men were lucky to make it back to Adelaide. However, some years later, in the course of six expeditions between 1858 and 1862, Stuart succeeded where Sturt had failed. Furthermore, in 1862 he managed to hack his way through the jungle of the Northern Territory and reach Van Diemen Gulf on the Indian Ocean, just east of Port Darwin. He almost lost his life on the return journey but, by reaching Adelaide, he became the first man to travel south to north across Australia and survive the journey back.

xxxxStuart was born in Dysart, Fifeshire, Scotland and was trained as a civil engineer at the Scottish Naval and Military Academy. Ill-health prevented him from taking up a military career, so, in search of adventure, he emigrated to South Australia in 1838 at the age of 23. There he worked as a surveyor, marking out plots for new settlers, and gaining a sound knowledge of the outback, its terrain and its harsh living conditions. In 1844, as noted above, he joined Sturt’s expedition into the interior, and gained valuable experience in the field of exploration. After a great deal of hardship the party managed to return to Adelaide in 1846, but it took him over a year to recover from exhaustion and scurvy.

xxxxxStuart was now convinced, however, that it was possible to reach the centre point of the continent and then journey to the north coast. He returned to his trade as a private surveyor but, starting in 1858, he led a series of his own expeditions into the interior. OOO He first explored the area immediately north of Adelaide with the help of an Aboriginal tracker. He reached as far as Streaky Bay, a journey of some 750 miles through unexplored bush - and returned the following year to make a survey of the region. Then, undeterred by the hardship he had suffered during this daunting task, he began his expedition to the centre of Australia in March 1860, together with two companions. O It proved a march into the history books. Despite the inevitable heat, thirst and hunger, - and the hostility of some Aboriginals - he reached the geographical centre of the continent, the first explorer to do so, and returned to a hero’s welcome.

xxxxxStuart was now convinced, however, that it was possible to reach the centre point of the continent and then journey to the north coast. He returned to his trade as a private surveyor but, starting in 1858, he led a series of his own expeditions into the interior. OOO He first explored the area immediately north of Adelaide with the help of an Aboriginal tracker. He reached as far as Streaky Bay, a journey of some 750 miles through unexplored bush - and returned the following year to make a survey of the region. Then, undeterred by the hardship he had suffered during this daunting task, he began his expedition to the centre of Australia in March 1860, together with two companions. O It proved a march into the history books. Despite the inevitable heat, thirst and hunger, - and the hostility of some Aboriginals - he reached the geographical centre of the continent, the first explorer to do so, and returned to a hero’s welcome.

xxxxxThe following year he planned an even more remarkable journey. O Starting out in January with a party of eleven men and 49 horses he aimed to be the first man to cross Australia from south to north, a feat which carried with it a government reward of £2000. Having crossed the vast inland region he reached Newcastle Waters, but was then confronted with dense bushland and was forced to return. Undeterred, he led another expedition, starting out in December 1861. O This time he met with success. Seven months later, on the 24th July 1862, having hacked their way through the jungle of the Northern Territory, the party reached the north coast at Van Diemen Gulf, close to Darwin. But this expedition, and particularly the return journey, took its toll on his health. He received another great welcome in Adelaide, but he came back an exhausted, broken man. For the last part of the journey he had to be carried on a stretcher, and he never recovered from the hardships he had suffered.

xxxxxFor his achievements he was awarded £3,000 and granted 1000 square miles of grazing country, rent free for seven years, in the interior he had done so much to discover. He returned to Scotland and lectured on his exploits, but this soon became too much for him and he went to live with his sister in London. He died there in June 1866, and was buried in Kensal Green cemetery. His birthplace is now a  museum recording his life and works.

museum recording his life and works.

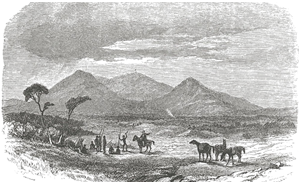

xxxxxStuart was the most competent and successful of Australia’s interior explorers, and his achievements were the more remarkable because of his slight, small build and the illness that plagued him from his youth, probably tuberculosis. No explorer has surpassed his courage and determination, and none has accomplished more. His expeditions opened up a vast new swathe of territory, some of it useful pasture land, and the overland telegraph, completed in 1872, followed the route he took - as does the highway from Adelaide to Darwin, named after him. His name is also remembered by the Central Mount Stuart (illustrated), not far from the centre of the continent, though, ironically enough, he actually gave the name Sturt to this mount when he discovered it in 1860.

xxxxxStuart’s crossing of the continent was a victory for his courage and determination, but he was not the first to achieve this feat. This honour went to his two rivals, Robert Burke and William Wills. They reached the Gulf of Carpentaria in February 1861 but, unlike Stuart, they failed to return.

Including:

Robert O’Hara Burke

and William John Wills

Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va-1837-1861-Va

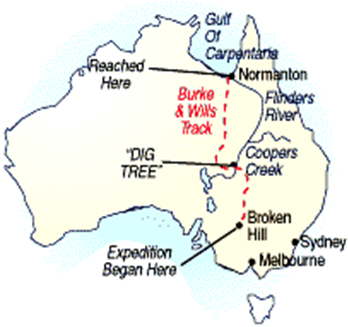

xxxxxBut the Scottish-born explorer John Stuart was not the first man to cross Australia from south to north. That honour went to his rivals, Robert O’Hara Burke (1820-1861) and the young surveyor William John Wills (1834-1861), though both failed to make the return journey. Their well-equipped expedition set off from Melbourne in August 1860, but on reaching the interior, Burke decided that only a party of four would complete the rest of the journey. They managed to reach the Gulf of Carpentaria in February 1861, but on their return journey Charles Gray died en route and the other three found that the camp at Coopers Creek was deserted, the rest of the expedition having left ten hours earlier after waiting for four months. They decided to make for Mount Hopeless, 150 miles away, but en route Burke and Wills died of exhaustion and starvation. John King managed to stay alive, helped by Aboriginals, and was rescued by a search party. The blame for these deaths is generally attributed to Burke’s lack of experience - he was a police inspector in Victoria before leading the expedition - and to his unwillingness to take advice from others or seek assistance from the Aboriginals, particular on the return journey. An account of the fateful expedition was provided in the log kept by Wills. In the 19th century men like Flinders, Sturt, Eyre, Leichhardt, Stuart and Burke opened up much of the remote areas of Australia, but the territory was not completely explored until the coming of the automobile and the aeroplane at the turn of the century.

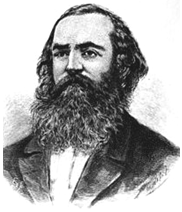

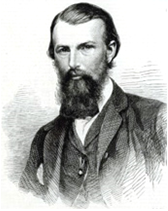

xxxxxBut despite his endeavours, Stuart was not the first explorer to journey across Australia from south to north. That honour went to his rivals, Robrt O’Hara Burke (1820-1861) (illustrated left) and the young surveyor William John Wills (1834-1861) (illustrated right). They reached the mongrove swamp on the Gulf of Carpentaria in February 1861 while he was making his first and unsuccessful attempt to reach the north coast. What they failed to do, however, unlike Stuart, was to make a safe return. Both perished on their homeward journey. Indeed, it was on the very day that Stuart’s return from Darwin was being celebrated in Adelaide that the bones of Burke and Wills were being buried in Melbourne.

xxxxxBut despite his endeavours, Stuart was not the first explorer to journey across Australia from south to north. That honour went to his rivals, Robrt O’Hara Burke (1820-1861) (illustrated left) and the young surveyor William John Wills (1834-1861) (illustrated right). They reached the mongrove swamp on the Gulf of Carpentaria in February 1861 while he was making his first and unsuccessful attempt to reach the north coast. What they failed to do, however, unlike Stuart, was to make a safe return. Both perished on their homeward journey. Indeed, it was on the very day that Stuart’s return from Darwin was being celebrated in Adelaide that the bones of Burke and Wills were being buried in Melbourne.

xxxxxIt was in August 1860 that the Irish explorer Robert Burke left Melbourne with a party of 18, among whom was his second-in-command, the Englishman William Wills. The original plan was for an advance party to set up bases en route to assist in the movement of heavier supplies, but about half way into the expedition, at Coopers Creek on the Barcoo River, Burke suddenly decided to go the rest of the way accompanied only by Wills and two other members of the advance party, Charles Gray and John King. The four managed to reach the outskirts of the Gulf of Carpentaria but, unable to cross the swamps or make their way through the jungle terrain, they then turned back. Gray died of exhaustion soon afterwards, and the other three, having managed to reach the Barcoo camp, found it deserted. The rear party had left that very morning after waiting for four months. Food had been left for them at a marked spot to enable them to reach the nearest town, but, unwisely as it proved, they decided not to delay, but to make straight for Mount Hopeless where help was at hand. It was a journey of 150 miles and they never made it. Lost and starving, they eventually could go no further. Burke and Wills died of hunger and exhaustion, but King, cared for by some local Aboriginals, managed to survive and was rescued by a search party. Wills’ account of the expedition was found on his body.

xxxxxIt was in August 1860 that the Irish explorer Robert Burke left Melbourne with a party of 18, among whom was his second-in-command, the Englishman William Wills. The original plan was for an advance party to set up bases en route to assist in the movement of heavier supplies, but about half way into the expedition, at Coopers Creek on the Barcoo River, Burke suddenly decided to go the rest of the way accompanied only by Wills and two other members of the advance party, Charles Gray and John King. The four managed to reach the outskirts of the Gulf of Carpentaria but, unable to cross the swamps or make their way through the jungle terrain, they then turned back. Gray died of exhaustion soon afterwards, and the other three, having managed to reach the Barcoo camp, found it deserted. The rear party had left that very morning after waiting for four months. Food had been left for them at a marked spot to enable them to reach the nearest town, but, unwisely as it proved, they decided not to delay, but to make straight for Mount Hopeless where help was at hand. It was a journey of 150 miles and they never made it. Lost and starving, they eventually could go no further. Burke and Wills died of hunger and exhaustion, but King, cared for by some local Aboriginals, managed to survive and was rescued by a search party. Wills’ account of the expedition was found on his body.

xxxxxMuch of the blame for the deaths of these three men, plus others of the party, has been attributed to Burke’s lack of experience and his unwillingness to take advice from others or seek the assistance of the Aboriginals, particularly on the return journey. The expedition itself, made up of 18 officers and men, 26 camels and sufficient food supplies for two years, was more than adequately equipped, but Burke’s decision to complete half the journey with just three other men, advancing well ahead of the support party, proved a recipe for disaster.

xxxxxMuch of the blame for the deaths of these three men, plus others of the party, has been attributed to Burke’s lack of experience and his unwillingness to take advice from others or seek the assistance of the Aboriginals, particularly on the return journey. The expedition itself, made up of 18 officers and men, 26 camels and sufficient food supplies for two years, was more than adequately equipped, but Burke’s decision to complete half the journey with just three other men, advancing well ahead of the support party, proved a recipe for disaster.

xxxxxBurke was born in County Galway, Ireland, but was educated in Belgium. He served in the Austrian army and then the Royal Irish Constabulary before emigrating to Australia in 1853. He found employment as a police inspector at Castlemain, Victoria before embarking on the fateful expedition, an account of which was obtained from the journal written by Wills.

xxxxxExplorers in the 19th century, like Flinders, Sturt, Eyre, Leichhardt, Stuart, Burke and Wills, played a major part in opening up the remote interior regions of Australia, but many more expeditions were needed. Indeed, the territory was not fully explored and mapped until the turn of the century with the coming of the automobile and the aeroplane.

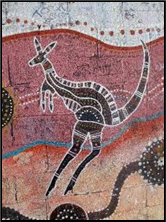

xxxxxIncidentally, the Aboriginals - meaning “original inhabitants” - are thought to have migrated from southeast Asia and settled in Australia more than 75,000 to 100,000 years ago. Made up of a number of distinctive clans, in the past they lived by hunting, fishing and the gathering of fruits and vegetables. Today, the majority have been assimilated into the rural or urban life of Australian society. As a people they have a spiritual connection with the land of their region, and it is for this reason that in recent years certain areas and landmarks have been returned to their ownership. Noted for their unique contribution to art (illustrated), many of their drawings and paintings tell the stories of their “Dreamtime”, when their ancestral spirits came upon earth and created its landscape and all forms of life. Today the Aboriginals number around 250,000.

xxxxxIncidentally, the Aboriginals - meaning “original inhabitants” - are thought to have migrated from southeast Asia and settled in Australia more than 75,000 to 100,000 years ago. Made up of a number of distinctive clans, in the past they lived by hunting, fishing and the gathering of fruits and vegetables. Today, the majority have been assimilated into the rural or urban life of Australian society. As a people they have a spiritual connection with the land of their region, and it is for this reason that in recent years certain areas and landmarks have been returned to their ownership. Noted for their unique contribution to art (illustrated), many of their drawings and paintings tell the stories of their “Dreamtime”, when their ancestral spirits came upon earth and created its landscape and all forms of life. Today the Aboriginals number around 250,000.

xxxxxIllustrated here are three examples of Aboriginal rock art:

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Scottish-

xxxxxAs we have seen, the Scottish- xxxxxStuart was now convinced, however, that it was possible to reach the centre point of the continent and then journey to the north coast. He returned to his trade as a private surveyor but, starting in 1858, he led a series of his own expeditions into the interior. OOO He first explored the area immediately north of Adelaide with the help of an Aboriginal tracker. He reached as far as Streaky Bay, a journey of some 750 miles through unexplored bush -

xxxxxStuart was now convinced, however, that it was possible to reach the centre point of the continent and then journey to the north coast. He returned to his trade as a private surveyor but, starting in 1858, he led a series of his own expeditions into the interior. OOO He first explored the area immediately north of Adelaide with the help of an Aboriginal tracker. He reached as far as Streaky Bay, a journey of some 750 miles through unexplored bush - museum recording his life and works.

museum recording his life and works.

xxxxxBut despite his endeavours, Stuart was not the first explorer to journey across Australia from south to north. That honour went to his rivals, Robrt O’Hara Burke (1820-

xxxxxBut despite his endeavours, Stuart was not the first explorer to journey across Australia from south to north. That honour went to his rivals, Robrt O’Hara Burke (1820- xxxxxIt was in August 1860 that the Irish explorer Robert Burke left Melbourne with a party of 18, among whom was his second-

xxxxxIt was in August 1860 that the Irish explorer Robert Burke left Melbourne with a party of 18, among whom was his second- xxxxxMuch of the blame for the deaths of these three men, plus others of the party, has been attributed to Burke’s lack of experience and his unwillingness to take advice from others or seek the assistance of the Aboriginals, particularly on the return journey. The expedition itself, made up of 18 officers and men, 26 camels and sufficient food supplies for two years, was more than adequately equipped, but Burke’s decision to complete half the journey with just three other men, advancing well ahead of the support party, proved a recipe for disaster.

xxxxxMuch of the blame for the deaths of these three men, plus others of the party, has been attributed to Burke’s lack of experience and his unwillingness to take advice from others or seek the assistance of the Aboriginals, particularly on the return journey. The expedition itself, made up of 18 officers and men, 26 camels and sufficient food supplies for two years, was more than adequately equipped, but Burke’s decision to complete half the journey with just three other men, advancing well ahead of the support party, proved a recipe for disaster.

xxxxxIncidentally, the Aboriginals -

xxxxxIncidentally, the Aboriginals -