xxxxxThe German

composer and conductor Richard Strauss, the last of the Romantics,

is especially remembered today for his mastery of the symphonic

poem and his operatic works. His ten tone poems, which began with

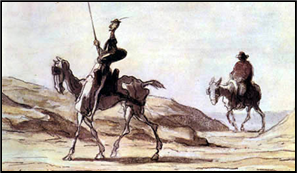

Don Juan in 1888 and included Thus

Spoke Zarathustra, Don Quixote

of 1897, and A Hero’s life, were brilliantly orchestrated,

but their vastness and powerful, expressive music shocked his

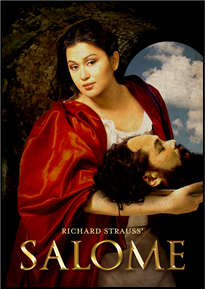

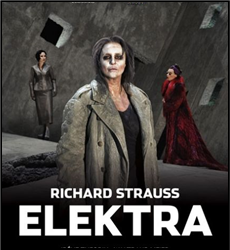

contemporaries. And this “modernism” was continued in Salome

of 1905 and Elektra four years later,

two operas which offended public good taste. However, after the

composition of his love story Knight of

the Rose, produced in 1911, his operas -

RICHARD STRAUSS 1864 -

Acknowledgements

Strauss: detail,

by the German painter Max Liebermann (1847-

xxxxxThe German composer and conductor Richard Strauss is

primarily remembered today on two counts: His mastery of the

symphonic poem -

xxxxxThe German composer and conductor Richard Strauss is

primarily remembered today on two counts: His mastery of the

symphonic poem -

xxxxxStrauss was born in Munich, the son of a celebrated horn player. He attended the local gymnasium for his general education, but he had inherited his father’s musical skills. He was playing the piano and violin by the age of five, composing by the age of six, and studying theory by the age of eleven. As a young man he played in a local amateur orchestra, and it was then that he first tried his hand at conducting. By then he had written a large number of pieces, including the Festival March, a serenade for wind instruments, a symphony and a violin concerto. Like all his early works, these leaned heavily upon the classical and romantic masters. In 1882 he attended Munich University, but he never worked for a degree and left the following year. By 1884 he was in Berlin, studying part time and playing the piano at various musical functions.

xxxxxIt was while in Berlin that Strauss met the renowned

conductor Hans von Bulow (illustrated) -

xxxxxIt was while in Berlin that Strauss met the renowned

conductor Hans von Bulow (illustrated) -

xxxxxIn 1889 Strauss became the director of the Weimar Court

Orchestra. He continued to compose traditional works, but it was in

that year that his symphonic poem Don Juan,

premiered in the November, gave final notice that a new force in

music had arrived. Charged with a score that demanded an orchestra

of unprecedented size, its powerful, expressive music, and its

variety of passages -

xxxxxIn 1889 Strauss became the director of the Weimar Court

Orchestra. He continued to compose traditional works, but it was in

that year that his symphonic poem Don Juan,

premiered in the November, gave final notice that a new force in

music had arrived. Charged with a score that demanded an orchestra

of unprecedented size, its powerful, expressive music, and its

variety of passages -

xxxxxThese works, characterised by audacious, colourful

orchestration and seen by Strauss as “the musical expression and

development of my emotions”, shocked audiences by their disturbing

non-

xxxxxThese works, characterised by audacious, colourful

orchestration and seen by Strauss as “the musical expression and

development of my emotions”, shocked audiences by their disturbing

non- the

erotic Dance of the Seven Veils, and

ending with the scene in which Salome declares her love to the

severed head of John the Baptist, it was roundly condemned for its

blasphemous treatment of a Biblical subject. Newspapers had a field

day, and one described the opera as “moral stench”. (On the other

hand the Austrian composer and conductor Gustav Mahler regarded it

as a “live volcano” and a work of

genius!). Then four years later, Sophocles’ Elektra,

a gloomy drama of bloodthirsty revenge, stunned its audiences by its

near atonal music, its attempt to create a new kind of melody, and

its bewildering use of leitmotivs. New ideas, Strauss responded,

must “search for new forms”.

the

erotic Dance of the Seven Veils, and

ending with the scene in which Salome declares her love to the

severed head of John the Baptist, it was roundly condemned for its

blasphemous treatment of a Biblical subject. Newspapers had a field

day, and one described the opera as “moral stench”. (On the other

hand the Austrian composer and conductor Gustav Mahler regarded it

as a “live volcano” and a work of

genius!). Then four years later, Sophocles’ Elektra,

a gloomy drama of bloodthirsty revenge, stunned its audiences by its

near atonal music, its attempt to create a new kind of melody, and

its bewildering use of leitmotivs. New ideas, Strauss responded,

must “search for new forms”.

xxxxxAfterxSalome, Strauss went into partnership with the Austrian

poet and librettist Hugo von

Hofmannsthal (1874-

xxxxxAfterxSalome, Strauss went into partnership with the Austrian

poet and librettist Hugo von

Hofmannsthal (1874-

xxxxxStrauss

is particularly well known for his symphonic poems and his operas,

16 in total, but he also wrote a variety of other works, including

two horn concertos -

xxxxxAlong

side Strauss’ brilliance as a composer went his skill as a

conductor, influenced in the main by his mentor Bulow. For most of

his life he conducted important orchestras throughout Germany and

Austria, and in 1891, at the invitation of Cosima Wagner, he

conducted the first performance of Tannhauser

to be given at the Bayreuth Festival. He was conductor of the Berlin

Philharmonic Orchestra from 1894 to 1898, conductor and musical

director of the Berlin Royal Opera from 1898 to 1919, and co-

xxxxxDuring the Nazi regime Strauss was appointed music minister in 1933, but was dismissed two years later for working with a Jewish librettist. The opera in question, The Silent Woman, was banned by the government. After the war he was cleared of any collaboration with the Nazi party, and spent the rest of his life at his country home at Garmisch in Bavaira. He died there in September 1949.

xxxxxStrauss

was the last great composer of the romantic tradition, and a worthy

successor to Wagner in the field of German opera. Despite his period

of modernism, he perfected a form -

xxxxxIncidentally, Strauss, a

quiet, modest man by nature, married the opera soprano Pauline de

Ahna in 1894. She was a forceful woman, but she encouraged his work,

and the marriage appeared to be a happy one. They had one son,

Franz, and his marriage to a Jewish woman in 1924 made matters

difficult for the family during the Nazi regime. ……

xxxxxIncidentally, Strauss, a

quiet, modest man by nature, married the opera soprano Pauline de

Ahna in 1894. She was a forceful woman, but she encouraged his work,

and the marriage appeared to be a happy one. They had one son,

Franz, and his marriage to a Jewish woman in 1924 made matters

difficult for the family during the Nazi regime. ……

xxxxx…… Strauss composed the Olympic Hymn for the opening of the Olympic Games in Berlin in 1936. The theme was taken from a symphony he planned but never finished. While writing it he confessed to a friend that he had no time for sport of any kind!

Vc-

Including:

Gustav Mahler

and Paul Dukas

xxxxxThe Austrian

composer and conductor Gustav Mahler (1860-

xxxxxA contemporary of Richard Strauss who was also a

competent composer and conductor was the Austrian Gustav

Mahler (1860-

xxxxxA contemporary of Richard Strauss who was also a

competent composer and conductor was the Austrian Gustav

Mahler (1860-

xxxxxMahler was born at Kaliste in Bohemia (now in the Czech Republic), the son of a Jewish shopkeeper. A few months later the family moved to the nearby town of Jihlava, and it was there that Mahler grew up. His early years were not particularly happy ones. As a Jew he was conscious of being an outsider, and his home life was marred by strained relations between his parents. These racial and family tensions might well account for his somewhat troubled personality, and his difficulty in relating to other people. Nonetheless, he showed early talent as a pianist and, influenced by local band and folk music, was trying his hand at composition by the age of six. He made his debut as a pianist when he was ten, and was accepted as a pupil at the Vienna Conservatory just five years later. On completing his musical studies, he attended lectures at the city’s university, and it was there that he was taught and influenced by the Austrian composer Anton Bruckner. After leaving the university he earned his living as a teacher, but was anxious to make his way as a composer. However, his first significant attempt, his cantata The Song of Sorrow, completed in 1880, failed to win the Conservatory’s Beethoven Prize and, on the advice of his piano teacher, he took up a career as a conductor, confining his composition to his leisure time.

xxxxxOver the next 17 years, by dint of constant hard work

and a ruthless determination to succeed, he battled his way to the

top of his chosen profession. He began his career as assistant

conductor in a summer theatre at the Austrian spa town of Bad Hall,

but then gradually gained experience by way of theatres and opera

houses across Europe. During the 1880s these included theatres at

Ljubljana, Olmutz and Kassel and opera houses in Prague, Leipzig and

Budapest. In 1901 he gained his first permanent position as chief

conductor with the Hamburg Opera House, and three years later,

following the death of Hans von Bulow, was appointed conductor of

the Hamburg Symphony Orchestra.

xxxxxOver the next 17 years, by dint of constant hard work

and a ruthless determination to succeed, he battled his way to the

top of his chosen profession. He began his career as assistant

conductor in a summer theatre at the Austrian spa town of Bad Hall,

but then gradually gained experience by way of theatres and opera

houses across Europe. During the 1880s these included theatres at

Ljubljana, Olmutz and Kassel and opera houses in Prague, Leipzig and

Budapest. In 1901 he gained his first permanent position as chief

conductor with the Hamburg Opera House, and three years later,

following the death of Hans von Bulow, was appointed conductor of

the Hamburg Symphony Orchestra.

xxxxxIt

was while in Hamburg that he was seen by Richard Strauss and Bulow,

both of whom were impressed by his skill as a conductor, and the way

in which he had enhanced the reputation of the  Hamburg

Opera. In 1892 he took the company to London to give the first

performances of Wagner’s Ring Cycle, and

in December 1895 he premiered his own Resurrection

Symphony in Berlin. It must be said that in many of these

appointments his uncompromising stance on achieving the highest of

standards, and the despotic regime he imposed to this end, did not

win him many friends. A number of orchestras were pleased to see him

move on! Personality apart, during this time he did succeed in

promoting the operas of Mozart, Weber and Wagner.

Hamburg

Opera. In 1892 he took the company to London to give the first

performances of Wagner’s Ring Cycle, and

in December 1895 he premiered his own Resurrection

Symphony in Berlin. It must be said that in many of these

appointments his uncompromising stance on achieving the highest of

standards, and the despotic regime he imposed to this end, did not

win him many friends. A number of orchestras were pleased to see him

move on! Personality apart, during this time he did succeed in

promoting the operas of Mozart, Weber and Wagner.

xxxxxMahler was appointed director of the Vienna Court Opera in 1897 at the age of 37. Over the next ten years, by his ruthless quest for perfection, he made Vienna supreme among the opera houses of the world. These were Vienna’s golden years. He cleared the company of its debts and provided performances which set the standards by which others could be judged. In so doing he alienated many by his long, gruelling periods of preparation and rehearsal, but no one could question his immense dedication and determination. And the tours he made across Europe during his time as director added to his fame as a conductor of outstanding merit.

xxxxxExhausted

and weakened by overwork and the beginnings of a serious heart

condition -

xxxxxAs

far as composing w as

concerned, Mahler regarded himself as a part-

as

concerned, Mahler regarded himself as a part-

xxxxxHis

first three symphonies were programme works and incorporated themes

from the German folk anthology entitled The

Youth’s Magic Horn. They sought to find a reason for human

existence in a world which was dominated by pain, despair and the

uncertainties of death. The First,

composed in 1888, lent heavily upon his song cycle Songs

of a Wayfarer, and is noted especially for its macabre

funeral march. The Second, his Resurrection,

complete with soloists and chorus, and based on

Beethoven’s Ninth

Symphony, opened with a funeral ceremony but ended

optimistically with its spectacular choral finale, a joyous

confirmation of the Christian belief in immortality. The Third,

completed in 1896, a vast work of six movements, again with soloist

and chorus -

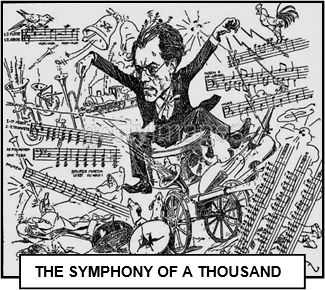

xxxxxHis

next three symphonies were composed while he was in Vienna. The Fourth, the portrayal of a child’s vision of

heaven, was based upon a song he had written in 1892 entitled The Heavenly Life.

This provided themes for the first three movements and is sung in

full in the fourth. The Fifth Symphony is

remembered especially for its opening trumpet fanfare -

xxxxxHis Seventh Symphony -

xxxxxHis Seventh Symphony -

xxxxxBy

the time Mahler returned home from New York he was fatally ill and

had only a few weeks to live. He died in Vienna in May 1911, and was

buried at Grinzing cemetery in the city. Mahler was first and

foremost an inspired conductor who, by his constant search for

perfection, raised the standard of interpretation and performance to

new heights. As a “part-

xxxxxIncidentally, bearing in mind

the “curse of the ninth” -

xxxxxIncidentally, bearing in mind

the “curse of the ninth” -

xxxxx…… The three hammer blows which bring to an end his Tragic Symphony No.6, premiered at Essen in

May 1906, were later seen as portending the three tragedies that

beset Mahler in 1907. In that year his three- etained

in some performances.

etained

in some performances.

xxxxxIt

was in this year, 1897, that the French

composer and teacher Paul Dukas (1865-

xxxxxDukas was born in Paris, and studied harmony, piano,

conducting and orchestration at the city’s Conservatoire. It was

there that he met the young French composer Claude Debussy, and they

became close friends. Following his military service, he worked as a

successful critic, and in 1910 returned to the Conservatoire to

teach composition. Among his other works were his concert overture King Lear, composed in 1883, his Symphony

in C major of 1896, his oriental ballet The

Genie, produced in 1912, and his Sonnet

de Ronsard for voice and piano, written in 1924. His

skilful orchestration has been described as an intoxicating mixture

of Debussy and Richard Strauss.

xxxxxDukas was born in Paris, and studied harmony, piano,

conducting and orchestration at the city’s Conservatoire. It was

there that he met the young French composer Claude Debussy, and they

became close friends. Following his military service, he worked as a

successful critic, and in 1910 returned to the Conservatoire to

teach composition. Among his other works were his concert overture King Lear, composed in 1883, his Symphony

in C major of 1896, his oriental ballet The

Genie, produced in 1912, and his Sonnet

de Ronsard for voice and piano, written in 1924. His

skilful orchestration has been described as an intoxicating mixture

of Debussy and Richard Strauss.

xxxxxDukas’

dazzling scherzo The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

became internationally famous in 1940 when the American film

producer Walt Disney featured it in his symphonic concert entitled Fantasia. The part of the apprentice was taken

by his cartoon character Mickey Mouse, and the Sorcerer was named

Yen Sid -