xxxxxThe Irish writer and playwright Richard Steele met his life-

xxxxxThe writer, playwright and politician Richard Steele was born in Dublin. He went to school at Charterhouse, London -

xxxxxThe writer, playwright and politician Richard Steele was born in Dublin. He went to school at Charterhouse, London -

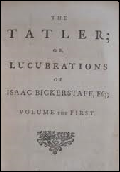

xxxxxIt was in April 1709 that, under the pseudonym of Isaac Bickerstaff, he brought out the first number of The Tatler, a magazine which came out three times a week, and was a mixture of literary articles and political comment. His old school friend, Joseph Addison, contributed a number of essays to this journal, and in March 1711 they worked together to produce the more famous periodical, The Spectator. Produced six days a week, it only ran until December the following year, but during its publication both Steele and Addison contributed well over 200 articles each, and it attracted a large number of readers. This was partly due to a character they conceived named Sir Roger de Coverley, a kindly if somewhat eccentric English squire who contributed a series of popular essays known as the Coverley papers.

xxxxxThese two periodicals, with their short stories, sketches and astute observations on the current social and political scene, might be seen as the beginning of popular journalism, but they were well written, set a good tone, and aimed to refine the manners of their readers. Thus their content was in marked contrast to the insensitivity and frequent licentiousness of much of Restoration literature. As Steele and Addison put it, their aim was not only to "bring philosophy out of the library and lead her to the tea table", but also "to enliven morality with wit, and to temper wit with morality". Truth, innocence, honour and virtue were seen as the "chief ornaments of life". These were worthy comments with which to mark the beginning in England of what came to be known as the Age of Enlightenment.

xxxxxThese two periodicals, with their short stories, sketches and astute observations on the current social and political scene, might be seen as the beginning of popular journalism, but they were well written, set a good tone, and aimed to refine the manners of their readers. Thus their content was in marked contrast to the insensitivity and frequent licentiousness of much of Restoration literature. As Steele and Addison put it, their aim was not only to "bring philosophy out of the library and lead her to the tea table", but also "to enliven morality with wit, and to temper wit with morality". Truth, innocence, honour and virtue were seen as the "chief ornaments of life". These were worthy comments with which to mark the beginning in England of what came to be known as the Age of Enlightenment.

xxxxxIn 1713 Steele launched his next venture The Guardian. This ran for 176 issues and was followed by a number of other periodicals, including The Reader, Town-

xxxxxBut for Steele, a good-

xxxxxIncidentally, there had been two early periodicals in England, The Compleat Library of 1691 and The Gentleman's Journal, produced the following year. They had contained articles and book reviews, but had lacked journalistic flair. Later, The Gentleman's Magazine, published in 1731, was the first publication to use the word "magazine". The term “Gazette” originated in Venice in the 16th century. A government news-

xxxxxIncidentally, there had been two early periodicals in England, The Compleat Library of 1691 and The Gentleman's Journal, produced the following year. They had contained articles and book reviews, but had lacked journalistic flair. Later, The Gentleman's Magazine, published in 1731, was the first publication to use the word "magazine". The term “Gazette” originated in Venice in the 16th century. A government news-

RICHARD STEELE 1672 -

(C2, J2, W3, AN, G1, G2)

Including:

Joseph Addison and

London Coffee Houses

xxxxxSteele's friendship with the poet and essayist Joseph Addison (1672-

xxxxxSteele's friendship with the poet and essayist Joseph Addison (1672-

xxxxxHe came to prominence in 1704 with his The Campaign, a poem commissioned by the government to celebrate Marlborough's victory at Blenheim. Addressed to Marlborough himself, this work proved immensely popular, and a grateful Whig party was only too happy to offer him employment in a succession of posts. In 1708 he was elected to parliament and appointed secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. In the following year he began contributing to Steele's Tatler magazine and in 1711 joined him as co-

xxxxxAfter The Spectator folded in 1712, he began writing his blank verse tragedy entitled Cato. Published in 1713, this further enhanced his reputation as a stylish writer, and as an astute observer of the current political scene, managing as it did to please both Whig and Tory at the same time! His periodical The Freeholder, published in December 1715 in support of the government, was also well received. He was appointed secretary of state in 1717, but by then he was suffering from ill-

xxxxxApart from the elegant, easy style in which they were written, Addison's essays were noted above all for their subtle humour, lively imagination and down-

xxxxxApart from the elegant, easy style in which they were written, Addison's essays were noted above all for their subtle humour, lively imagination and down-

xxxxxAddison numbered among his friends William Congreve, John Vanbrugh and Alexander Pope. In 1715, however, he fell out with Pope, a contributor to The Spectator, over a rival translation of the Iliad. Furthermore, his long friendship with Steele, a friendship which had produced such a highly successful partnership in the formative years of modern journalism, also came to an end. Their relationship became strained over their differing views on a bill restricting the peerage, and led to a total split just before Addison's death in 1719.

xxxxxIncidentally, we are told that on his deathbed Addison, a God-

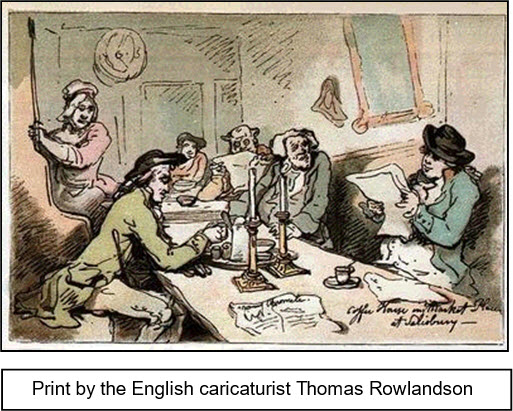

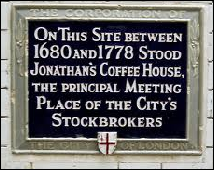

xxxxxAs we have seen, the first London coffee house was established in 1652 (CW). It proved very popular, and in the space of a few years hundreds had been opened across the city. These proved valuable for spreading news, exchanging gossip, and providing a primitive postal service. And before long many had become recognised as meeting places for a particular trade or profession. For example, St. James’ and the Cocoa Tree were frequented by politicians; business and insurance deals were carried out in Lloyd’s, Garraway’s and Jonathan’s; and scientists gathered at the Grecian coffee house. Over the years the literary world was served by Will’s, Button’s and the Bedford. Both Steele and Addison made good use of Button’s to improve public taste. During its heyday, stretching from the 1650s to the 1780s, the London coffee house played a vital part in widening interest in social, political and economic affairs. In particular, the forum they provided for open discussion contributed to the democratic process, and the business institutions they fostered gave Britain a head start in the commercial world of the 19th century.

xxxxxThe heyday of the London coffee house stretched over more than 130 years, from the 1650s to the 1780s, and by this reign (AN) these houses -

xxxxxThe heyday of the London coffee house stretched over more than 130 years, from the 1650s to the 1780s, and by this reign (AN) these houses -

All accounts of Gallantry, Pleasure, and Entertainment shall be under the Article of White's Chocolate-

xxxxxIn addition, these coffee-

xxxxxAs we have seen, it was in 1652 (CW) that, according to the most likely account, a merchant named Daniel Edwards allowed his servant, Christopher Bowman, and a young Turk named Pasqua Rosée, to open a coffee house in London in St. Michael’s Alley, Cornhill -

xxxxxFor the politicians at Westminster, there was the St. James’ or the Cocoa Tree near Pall Mall, depending upon your party allegiance. These houses provided much of the political news for Richard Steele’s Tatler, and they remained the meeting places for members of Parliament and the leading gentry well into the reign of George III. For members of the clergy, there were a number of houses situated around St. Paul’s Cathedral, whilst Lloyd’s, Garraway’s and Jonathan’s, all near to the Royal Exchange, were favoured by the business fraternity. Indeed, until 1773, when the stock exchange acquired its own premises, the stock-

xxxxxIn the literary world, the most famous coffee house was that established by William Urwin in Russell Street, Covent Garden. Known simply as Will’s, it was here that the poet and dramatist John Dryden held centre stage for some thirty years, discussing with men of letters their latest poem or play, and passing judgement on literary works both past and present with men like Samuel Pepys and Alexander Pope. With his departure, however, the conversation lost its sparkle and its literary merit, and by 1712 Button’s had become the new haunt of the “wits”. Here it was that Joseph Addison installed his letter-

xxxxxIn the literary world, the most famous coffee house was that established by William Urwin in Russell Street, Covent Garden. Known simply as Will’s, it was here that the poet and dramatist John Dryden held centre stage for some thirty years, discussing with men of letters their latest poem or play, and passing judgement on literary works both past and present with men like Samuel Pepys and Alexander Pope. With his departure, however, the conversation lost its sparkle and its literary merit, and by 1712 Button’s had become the new haunt of the “wits”. Here it was that Joseph Addison installed his letter- literature… teach him to think ... and provide him with general ideas on life and art.” In attempting to achieve this aim Addison was assisted, amongst others, by his colleagues Richard Steele, John Arbuthnot, and Jonathan Swift. Next came the “reign” of the Bedford coffee house, also located in Covent Garden. Regarded as “the emporium of wit, the seat of criticism, and the standard of taste”, this boasted of a company which included the novelist Henry Fielding, the artist William Hogarth, the actor David Garrick and the playwright Oliver Goldsmith.

literature… teach him to think ... and provide him with general ideas on life and art.” In attempting to achieve this aim Addison was assisted, amongst others, by his colleagues Richard Steele, John Arbuthnot, and Jonathan Swift. Next came the “reign” of the Bedford coffee house, also located in Covent Garden. Regarded as “the emporium of wit, the seat of criticism, and the standard of taste”, this boasted of a company which included the novelist Henry Fielding, the artist William Hogarth, the actor David Garrick and the playwright Oliver Goldsmith.

xxxxxScientists were also catered for. The Grecian Coffee House (illustrated), situated in the Strand, was the meeting place for the fellows of the Royal Society and other men of learning. Amongst those who studied the past and sought for the knowledge of the future, were Sir Isaac Newton himself, the great astronomer Edmund Halley, and the man who helped found the British Museum, Sir Hans Sloane. Such establishments were akin to the gentlemen’s clubs that eventually replaced them, but not all these haunts had so refined an air. The editor of the London Spy, one Ned Ward, writing about coffee houses at this time, had this to say about one particular establishment he visited:

There was a rabble going hither and thither, reminding me of a swarm of rats in a ruinous cheese-

xxxxxFor the most part, however, coffee houses were well run establishments. Having paid an entrance fee of one penny, all men were considered equal, and had no need to give way to a “finer man”. However, they had to be reasonably well dressed and adhere to a set of rules. There were fines, for example, for swearing (generally twelve pence), rowdy quarrelling was forbidden, and profanity and talk of a treasonable nature were not allowed.

xxxxxIn the  majority of houses gambling and games of chance were prohibited or severely restricted, but there were some notable exceptions. Indeed, some were given over to “Gallantry, Pleasure and Entertainment”, as Steele put it. White’s Chocolate House, for example, founded in 1693, was famous for its gaming rooms, catering for the gambling habit of the idle rich -

majority of houses gambling and games of chance were prohibited or severely restricted, but there were some notable exceptions. Indeed, some were given over to “Gallantry, Pleasure and Entertainment”, as Steele put it. White’s Chocolate House, for example, founded in 1693, was famous for its gaming rooms, catering for the gambling habit of the idle rich -

xxxxxAnd there were those houses where pleasure was not confined to the card table. A few were nothing more than brothels in disguise. Furthermore, even the most respectable houses were targets for the criminal fraternity and rakes on the make. They were ideal places for gathering information about the movement of goods and the exchange of money, and there were always those in attendance who could be duped into parting with part if not all of their ready cash. It was for this reason, among others, that the popularity of the coffee house began to decline towards the end of the 18th century. To safeguard their clientele many houses converted to private clubs where admission was by membership only. By this time, too, tea was replacing coffee as the national beverage, and the marked improvement in the dissemination of information and the postal service greatly reduced the social function of coffee houses.

xxxxxBut their passing must no t be allowed to detract from their one-

t be allowed to detract from their one-

xxxxxIncidentally, the Great Plague of London in 1665, and the Great Fire that followed it, seriously affected attendance at the city’s coffee houses, but they quickly recovered their popularity. And for some, like the novelist Daniel Defoe and the diarist Samuel Pepys, even these disasters did not deter them from making their daily visit to their favourite haunt. ……

xxxxx…… Coffee houses also became popular on the continent (particularly in Vienna) and in certain cities in North America, but, compared with their counterparts in London, they never acquired the same amount of importance in the life of the local community or in the service of their nations.

AN-

Acknowledgements

Steele: by the English painter Jonathan Richardson (1667-

xxxxxThe friendship between Richard Steele and the English poet and essayist Joseph Addison (1672-