THE SPITHEAD AND NORE NAVAL MUTINIES 1797 (G3b)

xxxxxIt was in April 1797, when Britain was at war with Revolutionary France, that a naval mutiny involving the crews of 16 ships took place at Spithead Anchorage off Portsmouth. The men, determined and well organised, demanded better pay and conditions -

XxxxxThe outbreak of a naval mutiny at Spithead, off Portsmouth, in April 1797 could hardly have come at a worse time for the British government. Despite the victory over a Spanish fleet at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in February, the opening years of an all-

xxxxxThe mutiny was mainly in protest against the living conditions then endured aboard ship. Even by the standards of the day, the conditions under which the men lived and worked were appalling. The food and lack of it was a major grievance. The biscuits were often riddled with weevils, the water was often stale, if not putrid, and the lack of fresh vegetables caused widespread scurvy. To this was to be added a meagre pay which had not been increased for decades, and the excessive flogging and other forms of brutality by which discipline was maintained.  And in many cases these hardships were borne by men who had been press-

And in many cases these hardships were borne by men who had been press-

xxxxxThe mutiny began in April 1797, when the crew aboard the Channel fleet’s flagship, the Queen Charlotte, refused to put to sea and called upon other ships to join in their protest. In all, sixteen ships refused to sail, their crews demanding better pay, conditions and treatment. The men took over command, ran their ships by committee, and forcibly put ashore officers accused of ill-

xxxxxFaced with such a critical situation and fearing that matters might become even worse, the government really had no alternative but to make concessions. The Admiralty promised better provisions and an increase in pay (the first since 1658), dismissed from the service over fifty officers accused of brutality, and granted a Royal Pardon to all those taking part in the mutiny. Such concessions were accepted by the men at Spithead, where, in general, acts of violence had been limited, and negotiations, led by Admiral Lord Howe, had been conducted in a peaceful manner via  elected representatives.

elected representatives.

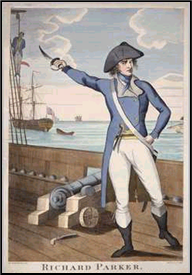

xxxxxButxit was a different story at the Nore, where political agitation was also at work. Here there were fears over the genuineness of the Royal Pardon, and much resentment over the fact that none of their officers had been dismissed. Furthermore, led by Richard Parker, a former midshipman (illustrated), the mutineers demanded a greater share in prize money, more shore leave, and changes in the Articles of War. When their demands were refused, they attempted to blockade the River Thames, and the government was forced to act. A bill was brought in to outlaw the mutineers, and the mutiny quickly collapsed. Parker and other ring leaders were hanged from the yardarm of HMS Sandwich, and many others were imprisoned or flogged.

xxxxxIncidentally, Captain William Bligh, the man who suffered at the hands of his own mutineers aboard the HMS Bounty in 1789, was one of the officers -

xxxxx…… Whenxthe mutiny of the North Sea fleet threatened to put an end to the blockade of the Dutch fleet -

xxxxx…… Whenxthe mutiny of the North Sea fleet threatened to put an end to the blockade of the Dutch fleet -

xxxxx…… The start of the mutiny was signalled by the sounding of five bells at 6.30 p.m. in what is known in the navy as the second dogwatch (there being two dogwatches or “divided” watches during the period 4 to 8 p.m.) Following the overthrow of the Nore mutiny, a slight change was made in the numbering system. The usual bells continued to be struck in the second dogwatch save for one exception. When it was 6.30 p.m. only one bell was sounded. So the signal for mutiny (five bells in the second dogwatch) was never heard in the Royal Navy again!

Acknowledgements

Spithead: by the English marine artist John Cleveley (c1712-

G3b-