xxxxxThe

Spanish-

THE SPANISH-

Acknowledgements

Map (Cuba):

licensed under Creative Commons –

www.eird.org/wiki/images/archive. Marti:

date and artist unknown. Weyler: artist

unknown, contained in The Boys of ’98 by

the American journalist James Otis Kaler (1848-

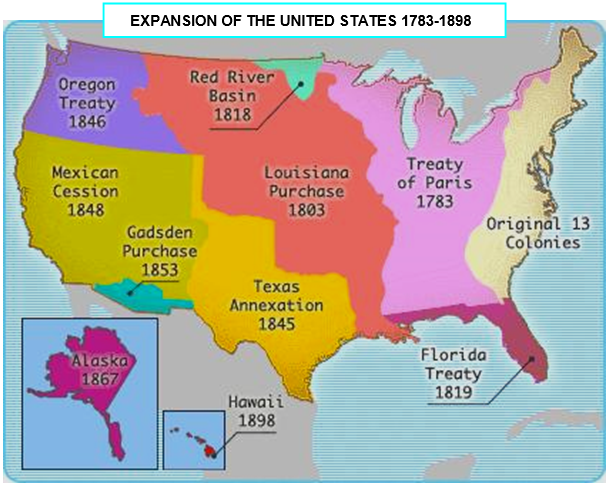

xxxxxThe conflict between the United

States and Spain in 1898 had its origins on the island of Cuba. As

we have seen, it was in October 1868

(Vb), following the overthrow of the

Spanish Queen Isabella, that the Cuban Revolt (the “Big War”)

broke out. A powerful protest against the hardships of Spanish

rule -

xxxxxThe conflict between the United

States and Spain in 1898 had its origins on the island of Cuba. As

we have seen, it was in October 1868

(Vb), following the overthrow of the

Spanish Queen Isabella, that the Cuban Revolt (the “Big War”)

broke out. A powerful protest against the hardships of Spanish

rule -

xxxxxBut these promises, like earlier ones, were not kept,

and opposition to Spanish rule mounted steadily, fuelled further

by higher taxes and trade restrictions. Anxuprising

in 1879 was quickly crushed (the “Little War”), but a better

organised and coordinated revolt broke out in 1895, led by José Marti (1853-

xxxxxBut these promises, like earlier ones, were not kept,

and opposition to Spanish rule mounted steadily, fuelled further

by higher taxes and trade restrictions. Anxuprising

in 1879 was quickly crushed (the “Little War”), but a better

organised and coordinated revolt broke out in 1895, led by José Marti (1853-

xxxxxIn order to crush the rebellion in quick time, Weyler

-

xxxxxIn order to crush the rebellion in quick time, Weyler

-

xxxxxIn 1897 the

Spanish government, alarmed at the public outcry, both

humanitarian and economic, recalled Weyler, put an end to the

prison camps, and offered the Cubans home rule, but it was all too

late. The Cuban rebels sensed victory, and would accept nothing

short of outright independence, whilst in the United States the

demand for intervention on behalf of the Cubans continued to gain

support.

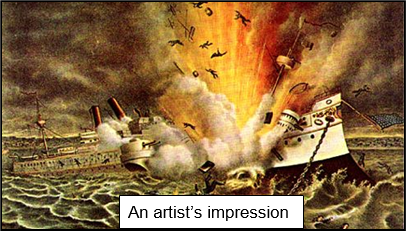

xxxxxA dramatic

turning point in the conflict came on the night of February 15th,

1898, when the US battleship Maine,

sent to Havana in order to protect U.S. citizens and property

during local rioting, was blown apart by an enormous explosion (illustrated). A total of 266

lives were lost, and many were wounded. The cause of the explosion

was never fully established, though later investigation tended to

suggest that it was caused by an accident in the boiler room. To the

United States government and the American public at large, however,

the Spanish were clearly the culprits. This,xtogether with the brutal measures being taken by them

to maintain their control of the island, finally triggered off

American intervention. In April the U.S. government, led by President William McKinley

(1843-

xxxxxThe war,

which only lasted ten weeks and ended in an overwhelming victory

for the United States, now took on a global dimension. The first

action by the United States took place in the Pacific. Axnaval force of six new warships, under the command of

Commodore George Dewey, sailed from Hong Kong and on May 1st

launched a surprise attack upon the ten Spanish ships anchored in

Manila Bay in

the Philippines. These obsolete vessels were quickly destroyed by

the steel ships of the U.S. Navy. The Spanish lost about 400 men.

American casualties amounted to seven wounded. Later, troops

landed and besieged the Spanish garrison in Manila,

taking command of the city by mid- At

the same time -

At

the same time -

xxxxxMeanwhile in

late June, U.S. troops under the command of General William R.

Shafter, a veteran of the American Civil War, landed in Cuba at

Daiquiri, just east of Santiago (arrowed on map), and advanced on the

city. The force of 16,000 men, made up of regular troops, two black

regiments, and a number of volunteer units (including the so-

xxxxxTwoxdays later a Spanish

naval squadron, made up of seven ships and commanded by Admiral

Pascual Cervera, attempted to break out of Santiago harbour, but, in what amounted to the largest naval

battle of the war, the squadron was destroyed in less than four

hours. The Americans only had

two casualties compared with the 474 suffered by the Spanish. The

city, together with 24,000 Spanish troops, then surrendered to

General Shafter on the 17th July, bringing the fighting to an end.

Later in the month, a U.S. force of some 3,500 men landed on

Puerto Rico (illustrated), and, after meeting slight resistance, occupied the

island. On August 12th the Spanish government signed an armistice.

xxxxxTwoxdays later a Spanish

naval squadron, made up of seven ships and commanded by Admiral

Pascual Cervera, attempted to break out of Santiago harbour, but, in what amounted to the largest naval

battle of the war, the squadron was destroyed in less than four

hours. The Americans only had

two casualties compared with the 474 suffered by the Spanish. The

city, together with 24,000 Spanish troops, then surrendered to

General Shafter on the 17th July, bringing the fighting to an end.

Later in the month, a U.S. force of some 3,500 men landed on

Puerto Rico (illustrated), and, after meeting slight resistance, occupied the

island. On August 12th the Spanish government signed an armistice.

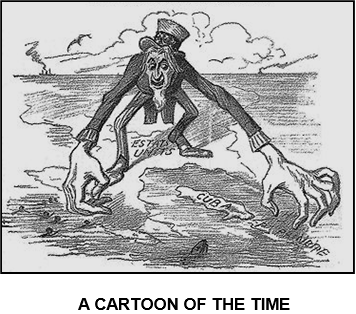

xxxxxByxthe

Treaty of Paris,

signed in December 1898, the Spanish recognised Cuba’s

independence and ceded their colonial territories, the

Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico, to the United States. By way of

compensation, the United States made a payment of $20 million to

Spain. In the Philippines there was some resistance to the

American occupation, but this was overcome by 1901. In the United

States, however, the annexation of these overseas territories did

not go unopposed. Many Democrats and a number of senior Republican

senators argued that this was a venture into colonialism and, as

such, was contrary to the principles of American democracy. The

Treaty was ratified in February 1899, but only by a margin of one

vote.

xxxxxByxthe

Treaty of Paris,

signed in December 1898, the Spanish recognised Cuba’s

independence and ceded their colonial territories, the

Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico, to the United States. By way of

compensation, the United States made a payment of $20 million to

Spain. In the Philippines there was some resistance to the

American occupation, but this was overcome by 1901. In the United

States, however, the annexation of these overseas territories did

not go unopposed. Many Democrats and a number of senior Republican

senators argued that this was a venture into colonialism and, as

such, was contrary to the principles of American democracy. The

Treaty was ratified in February 1899, but only by a margin of one

vote.

xxxxxThe Spanish-

xxxxxBy contrast,

the United States, having taken on and defeated a major European

nation, emerged from the conflict as a budding world power. It had

gained valuable staging posts in the Pacific and the Caribbean -

xxxxxLiberal

opposition apart, many Americans saw this overseas expansion as an

acceptable extension of their nation’s “manifest destiny”, the

idea, held earlier, that the United States was destined to rule

over the entire continent of North America. Ardent imperialists

argued that the control of such territories was essential for the

expansion of U.S. trade across the globe, whilst there were

others, the idealists, who saw it as the nation’s moral duty to

take up “the white man’s burden”. But whatever the reasons put

forward to justify America’s new stance, the result was the same:

the emergence of the United States as a player -

Vc-

Including:

Anglo-

Dispute of 1895

xxxxxIncidentally, the argument in

favour of the U.S. retaining Spain’s former colonies stemmed in

large part from The Influence of Sea Power

upon History, a persuasive appraisal of naval strategy by

the American naval officer Alfred

Thayler Mahan (1840-

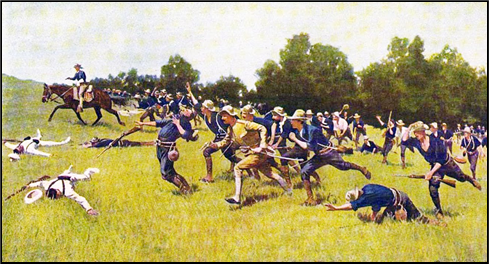

xxxxx…… The U.S. navy, modern

and well managed, acquitted itself well during the war, but

despite a number of land victories, the army was severely

criticised in general for its lack of preparedness and poor

planning. Amongxunits which escaped such

criticism was the 1st Volunteer Cavalry, organised by Theodore Roosevelt (1858-

xxxxx…… The U.S. navy, modern

and well managed, acquitted itself well during the war, but

despite a number of land victories, the army was severely

criticised in general for its lack of preparedness and poor

planning. Amongxunits which escaped such

criticism was the 1st Volunteer Cavalry, organised by Theodore Roosevelt (1858-

xxxxx…… The story goes that in 1897 the artist Frederic Remington was sent to Cuba by the newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst to cover the growing crisis there. After a short while, disappointed at the lack of action, Remington informed Hearst that there was no war and asked to be recalled. Back came the reply: “Please remain. You furnish the pictures, I’ll furnish the war.” There is no evidence to support this story! ……

xxxxx…… Thex1st U.S. Volunteer

Cavalry was commanded by Leonard Wood (1860-

xxxxxIt was in 1895, the year that the Cubans began their

attempt to overthrow their Spanish masters, that a long-

xxxxxIt was in 1895, the year that the Cubans began their

attempt to overthrow their Spanish masters, that a long-

xxxxxIn the event, Salisbury, faced at this time with more pressing colonial problems, agreed to submit the dispute to the American boundary commission and accepted its decision when it was made in October 1899. A showdown was thereby avoided, but it demonstrated that, even before its victory over the Spanish and its emergence on the world stage, the United States was beginning to flex its political muscles.