BRITAIN OUTLAWS THE SLAVE TRADE

1807 (G3c)

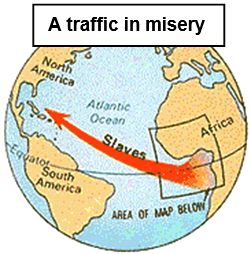

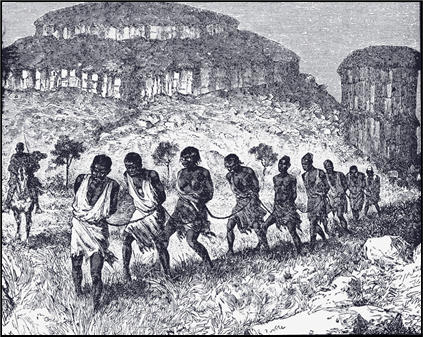

xxxxxThe Portuguese began the

trade in West African slaves around 1444, but the Trans-Atlantic

trade started in the first years of the 16th century. As we have

seen by the Asiento de Negros of 1713 (AN), this was a

despicable, degrading, traffic which took some 8 to 15 million

Africans to work in the New World. The Quakers were the first to

protest. In Britain, a Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade

was established in 1787, mainly the work of the philanthropist

Granville Sharp and the cleric Thomas Clarkson, assisted by the

pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood. A nationwide campaign was

launched, and gained the support of men such as John Wesley, William

Pitt, Edmund Burke and Charles Fox. The fight in Parliament was led by the brilliant orator

William Wilberforce. After many attempts to obtain legislation,

Britain outlawed the slave trade in 1807. As we shall see, however, it was not until 1833 (W4) that slavery was

banned in British colonies. Some European nations, such as Denmark,

had condemned slavery much earlier, but it was not until 1870 that

most others had followed suit. In the United States the northern

states opposed the slavery in the deep South, and this antagonism

gained momentum with the publication of Uncle

Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe in 1852. It took the

American Civil War, ten years later, to settle the issue.

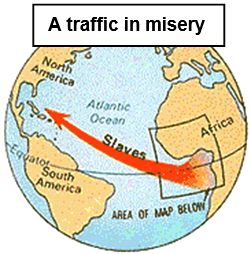

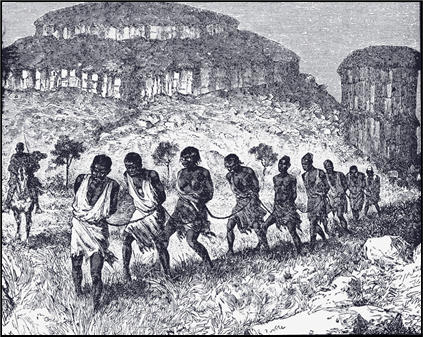

xxxxxThe trade in

West African slaves was begun by the Portuguese as early as 1444,

during their expeditions along the west coast of Africa. The Trans-Atlantic

trade by which young West Africans were transported to the New

World, began as a trickle in 1502 but, over the years, grew into a

vast torrent, stimulated by the growth of the plantation system.

Slavery had been a factor in life, of course, since the earliest

“civilisations”, but the trade across the Atlantic was particularly

degrading, harsh and inhuman, if only because of the dreadful

conditions which had to be endured - and were often not endured

- on the long outward sea journey. It was a traffic in misery

which, as we have seen by the Asiento de Negros

of 1713 (AN),

had reached enormous proportions by the beginning of the 18th

century.

xxxxxThe trade in

West African slaves was begun by the Portuguese as early as 1444,

during their expeditions along the west coast of Africa. The Trans-Atlantic

trade by which young West Africans were transported to the New

World, began as a trickle in 1502 but, over the years, grew into a

vast torrent, stimulated by the growth of the plantation system.

Slavery had been a factor in life, of course, since the earliest

“civilisations”, but the trade across the Atlantic was particularly

degrading, harsh and inhuman, if only because of the dreadful

conditions which had to be endured - and were often not endured

- on the long outward sea journey. It was a traffic in misery

which, as we have seen by the Asiento de Negros

of 1713 (AN),

had reached enormous proportions by the beginning of the 18th

century.

xxxxxThe Asiento

de Negros was a contract concerning the supply of slaves.

Initiated by the Spanish early in the 16th century, it was a

monopoly granted for the supply of Africans to work in the American

Spanish colonies. It is estimated that by this system alone some

450,000 Africans were transported to Spanish America between 1600

and 1750. But this was but a small percentage of the overall total.

From the middle of the 16th century until 1870, when the trade

virtually came to an end, it is thought that 8 to 15 million

Africans were forcibly taken to the New World. The vast majority

came from West and Central Africa, and most were put to work in the

Caribbean islands, the Guianas, and the Portuguese territory of

Brazil (some 40 percent alone). By comparison, only a small number

were settled on mainland Spanish America and in the former American

colonies.

xxxxxIn North America, as

in England, the first organised denunciation of slavery came from

the Quakers in the 1720s. At least by then an increasing number of

colonists were coming to regard it as an evil, necessary though it

might be. Indeed, in 1774 Rhode Island became the first state to

abolish slavery, and the other Northern states soon followed, but in

1788 the U.S. Constitution accepted that in the southern states it

would remain a fact of life, at least for the next twenty years. In

these states slavery had become such an integral part of the

agricultural and social economy, that its abolition was not seen as

a possibility, especially after the introduction of Eli Whitney’s

cotton gin, an invention of 1793 which required a vast increase in

the number of field hands in the plantations.

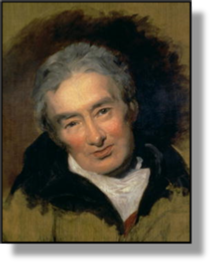

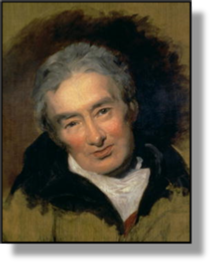

xxxxxIn Britain, the Quakers had campaigned against the slave

trade for many years, and had presented petitions to Parliament in

1783 and 1787. However, the first positive step was taken in 1787

with the establishment of the Society for

the Abolition of the Slave Trade. It was

formed by the English philanthropist Granville

Sharp (1735-1813) (illustrated

left), and the English cleric Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846)

(illustrated right),

together with the English pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood, a

man passionately interested in social reform. Of the twelve members

on the committee, nine were Quakers. Pamphlets and books supporting

this cause were widely distributed; agents and committees were set

up across the country; and for many years Clarkson toured the land

as a fact finder, collecting statements and equipment - such as

leg-shackles and branding irons - as evidence against the

trade. Much of this material was used by Wilberforce in his speeches

in the Commons. At this time, too, his Essay on

the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, published in

1786, gained the sympathy of many, including John Wesley, William

Pitt, Edmund Burke and Charles Fox. In addition, use was again made

of petitions to parliament. In the nationwide campaign of 1792, for

example, over 500 - containing some 400,000 signatures -

were presented to the Commons, coming from Scotland and Wales as

well as every county in England. And, as we have seen, the

autobiography The Life of Olaudah Equiano,

the African, published in 1789, proved

immensely influential.

xxxxxIn Britain, the Quakers had campaigned against the slave

trade for many years, and had presented petitions to Parliament in

1783 and 1787. However, the first positive step was taken in 1787

with the establishment of the Society for

the Abolition of the Slave Trade. It was

formed by the English philanthropist Granville

Sharp (1735-1813) (illustrated

left), and the English cleric Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846)

(illustrated right),

together with the English pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood, a

man passionately interested in social reform. Of the twelve members

on the committee, nine were Quakers. Pamphlets and books supporting

this cause were widely distributed; agents and committees were set

up across the country; and for many years Clarkson toured the land

as a fact finder, collecting statements and equipment - such as

leg-shackles and branding irons - as evidence against the

trade. Much of this material was used by Wilberforce in his speeches

in the Commons. At this time, too, his Essay on

the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, published in

1786, gained the sympathy of many, including John Wesley, William

Pitt, Edmund Burke and Charles Fox. In addition, use was again made

of petitions to parliament. In the nationwide campaign of 1792, for

example, over 500 - containing some 400,000 signatures -

were presented to the Commons, coming from Scotland and Wales as

well as every county in England. And, as we have seen, the

autobiography The Life of Olaudah Equiano,

the African, published in 1789, proved

immensely influential.

xxxxxIn these measures the

Society was greatly assisted by the member of parliament William Wilberforce. An ardent

supporter, and a close friend of the then prime minister William

Pitt, he led the campaign in the Commons. In 1791 his first bill to

abolish the slave trade was easily defeated, but in 1792, following

the presentation of the petitions, the House decided by 230 to 85

votes that the slave trade should be “gradually” abolished.

Unfortunately, this decision was taken against the alarming events

taking place on the continent - the outbreak of the

Revolutionary Wars in France and the overthrow of Louis XVI. These

events, and the violence they brought in their wake, quickly aroused

strong political reaction at home. The following year the Commons

was unwilling to discuss further the matter of the slave trade.

National movements calling for change were viewed with the utmost

suspicion. As a result, public enthusiasm for the cause virtually

collapsed, and although Wilberforce reintroduced the abolition bill

throughout the 1790s little progress was made.

xxxxxBut Wilberforce and his associates continued their

struggle. The bill fell again in 1804 and 1805, but with the news

that Napoleon was opposed to the emancipation of slaves, the mood

changed. In February 1807 Parliament

outlawed the slave trade by a huge majority, 114 to 15. The Act

provided for the search and seizure of ships thought to be involved

in such business, and it sanctioned payment for the liberation of

slaves. Slavery remained a fact in British colonies, but it was seen

as the first step on the road to the complete abolition of slavery

as such. At the Congress of Vienna in 1814 a number of countries

followed Britain’s lead, though a few, like Denmark in 1792, had

adopted such measures many years earlier. It was to be some time,

however, before this particularly vile trade had been banned by all

European countries and - more to the point - finally

brought to an end. In Britain, a further step was taken in 1823 with

the establishment of the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual

Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Dominions. As we shall

see, these aims were achieved in 1833

(W4), just three days before the death of

the society’s chief campaigner William Wilberforce.

xxxxxBut Wilberforce and his associates continued their

struggle. The bill fell again in 1804 and 1805, but with the news

that Napoleon was opposed to the emancipation of slaves, the mood

changed. In February 1807 Parliament

outlawed the slave trade by a huge majority, 114 to 15. The Act

provided for the search and seizure of ships thought to be involved

in such business, and it sanctioned payment for the liberation of

slaves. Slavery remained a fact in British colonies, but it was seen

as the first step on the road to the complete abolition of slavery

as such. At the Congress of Vienna in 1814 a number of countries

followed Britain’s lead, though a few, like Denmark in 1792, had

adopted such measures many years earlier. It was to be some time,

however, before this particularly vile trade had been banned by all

European countries and - more to the point - finally

brought to an end. In Britain, a further step was taken in 1823 with

the establishment of the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual

Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Dominions. As we shall

see, these aims were achieved in 1833

(W4), just three days before the death of

the society’s chief campaigner William Wilberforce.

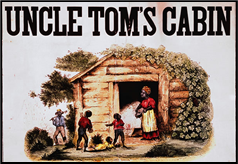

xxxxxAnd it was in that year, 1833, that the American Anti-Slavery

Society was formed in Philadelphia. As early as 1808 the U.S.

government had prohibited the import of slaves from Africa. In the

United States, however, it was a domestic not a colonial issue. The

whole question was bedevilled by the wide use of slavery in the

southern states, made the more divisive by the annexation of Texas

in 1845, a slave state of enormous size. And, as we shall see, the

anti-slave movement was given sharp impetus in 1852 with the

publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, an

emotional appeal by the American writer Harriet Elizabeth Beecher

Stowe. By then the United States was just ten years off the American

Civil War, a ferocious struggle fought to decide the very issue of

slavery.

xxxxxAnd it was in that year, 1833, that the American Anti-Slavery

Society was formed in Philadelphia. As early as 1808 the U.S.

government had prohibited the import of slaves from Africa. In the

United States, however, it was a domestic not a colonial issue. The

whole question was bedevilled by the wide use of slavery in the

southern states, made the more divisive by the annexation of Texas

in 1845, a slave state of enormous size. And, as we shall see, the

anti-slave movement was given sharp impetus in 1852 with the

publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, an

emotional appeal by the American writer Harriet Elizabeth Beecher

Stowe. By then the United States was just ten years off the American

Civil War, a ferocious struggle fought to decide the very issue of

slavery.

xxxxxMeanwhile in South America

slaves gained their freedom as each colony achieved its independence

- though it was often a freedom in name only - and slavery

was not abolished in Cuba and Brazil until the 1880s. For many

slaves, like those in the French and Dutch colonies, freedom was

still a long way off.

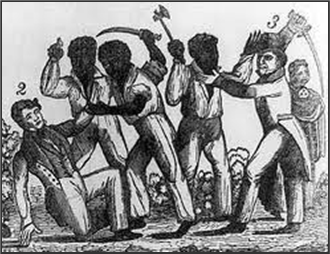

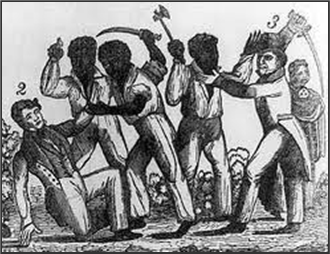

xxxxxIncidentally,

one of the biggest slave rebellions in the United States took place

in Virginia in 1831. Some 70 slaves, led by “Nat”

Turner - a Christian who believed he

was doing God’s work - went on the rampage and killed their

white masters and family members - some 60 in total. The

uprising was crushed within two days and 55 of the rebels, including

Turner, were caught and hanged. White gangs, out for revenge, then

beat, tortured and killed another 200 blacks, and Virginia and other

southern States passed new laws restricting the rights of assembly.

Acknowledgements

Sharp: detail,

by the German painter Johann Joseph Zoffany (1733-1810),

1779/81 – National Portrait Gallery, London. Clarkson: by the Swedish painter Carl Frederik von Breda

(1759-1818), 1788 – National Portrait Gallery, London. Rebellion: date and artist unknown – Rare Books and Special

Collections, Library of Congress, Washington. Wilberforce: detail, by the English portrait painter Sir Thomas

Lawrence (1769-1830), 1828 – National Portrait Gallery,

London. Slave Trade: date and artist

unknown. Holy Trinity: watercolour,

artist unknown, contained in Ecclesiastical

Topography Round London, first published in 1809.

Including:

William Wilberforce

G3c-1802-1820-G3c-1802-1820-G3c-1802-1820-G3c-1802-1820-G3c-1802-1820-G3c

xxxxxThe English philanthropist

William Wilberforce

(1759-1833) entered parliament in 1780 and, over the next 45

years, spent much of his time campaigning against the slave trade

and slavery in general. Supporting the Anti-Slavery Society

(formed in 1787) and, in particular, its members Granville Sharp and

Thomas Clarkson, he attempted many times to have a ban imposed.

Eventually, in 1792 the Commons agreed that the trade should be

“gradually” abolished but, as the French Revolution became more

violent, the matter was abandoned. A string of bills failed

throughout the 1790s, and in the early years of the 19th century,

but then the decision of Napoleon to re-impose slavery in the

French colonies turned the tide. In 1807 Parliament outlawed the slave trade by a massive

majority, and Wilberforce’s success was widely acclaimed. He retired

from the Commons in 1825, but he continued his support against

slavery and, as we shall see, just lived long enough to see slavery

abolished in all British possessions in 1833

(W4).

xxxxxAs we have seen, the English philanthropist and

politician William Wilberforce (1759-1833) played a leading part in the long

struggle to persuade the British government to abolish the slave

trade and slavery in general. An eloquent and persuasive orator, he

championed this worthy cause in parliament over many years and,

despite numerous setbacks, witnessed its successful conclusion just

before his death.

xxxxxAs we have seen, the English philanthropist and

politician William Wilberforce (1759-1833) played a leading part in the long

struggle to persuade the British government to abolish the slave

trade and slavery in general. An eloquent and persuasive orator, he

championed this worthy cause in parliament over many years and,

despite numerous setbacks, witnessed its successful conclusion just

before his death.

xxxxxThe son of a wealthy

merchant, Wilberforce was born in Hull, Yorkshire, in 1759, and

attended Cambridge University. It was here that he became a close

friend of William Pitt, the future Tory prime minister. They both

entered the House of Commons in 1780, where Wilberforce was soon

taking a leading part in demanding parliamentary reform and

political rights for Roman Catholics. Such was the strength of his

radical views that in 1792, at the height of the French Revolution,

he was appointed an honorary citizen of France, a title which proved

a political embarrassment as the revolution took its course. He was

obliged to support repressive measures to

prove his loyalty to king and country.

xxxxxHis support for the

anti-slavery campaign stemmed from his conversion to

Evangelical Christianity in 1784. Three years later he not only

helped to found the Anti-Slavery Society (though he did not

officially join it until 1794), but also the Proclamation Society,

an organisation aimed at reforming public morals and putting an end,

in particular, to the publication of obscenity. In that year he

wrote, "God Almighty has set before me two great objects - the abolition of the slave trade, and the reformation of manners." In

the war against slavery he became the acknowledged leader, supported

especially by the philanthropist Granville Sharp and the cleric

Thomas Clarkson.

abolition of the slave trade, and the reformation of manners." In

the war against slavery he became the acknowledged leader, supported

especially by the philanthropist Granville Sharp and the cleric

Thomas Clarkson.

xxxxxAs we have seen,

following the failure of the 1792 bid to introduce the gradual

abolition of the slave trade - thwarted by the government’s

reactionary measures in the face of the French Revolution - and

the failure of bills throughout the 1790s, the break through came in

the early years of the 19th Century. Attempts in 1804 and 1805 fared

no better but opinion changed drastically with the news that

slavery, abolished by the French government in 1794, had been re-imposed

by Napoleon throughout the French possessions. In February 1807

the British government outlawed the slave trade by a huge majority.

It is said that emotional tributes were made to Wilberforce that

evening, and members stood to applaud his efforts. However, as we

shall see, it was to be another 25 years before his second aim, the

abolition of slavery throughout the British Dominions, was to be

realised in July 1833 (W4).

Having retired in 1825, in this achievement he was to play a

significant but less active role.

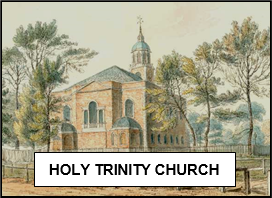

xxxxxIncidentally, when the Anti-Slavery

Society was first formed in 1787 - officially known as “The

Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade” - its

members were derisively called “Saints”, but from 1797 they became

known as the “Clapham Sect”. This was because Wilberforce was a

member of a group of evangelical Christians centred on the Holy

Trinity Church, Clapham Common, south London, where John Venn (1759-1813),

one of the founders of the Church Missionary Society, was the

Rector. Apart from their support for the anti-slavery movement,

the members of Holy Trinity Church were also opposed to cruel sports

and gambling, worked for prison reform, and sponsored several

missionaries at home and overseas.

xxxxxIncidentally, when the Anti-Slavery

Society was first formed in 1787 - officially known as “The

Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade” - its

members were derisively called “Saints”, but from 1797 they became

known as the “Clapham Sect”. This was because Wilberforce was a

member of a group of evangelical Christians centred on the Holy

Trinity Church, Clapham Common, south London, where John Venn (1759-1813),

one of the founders of the Church Missionary Society, was the

Rector. Apart from their support for the anti-slavery movement,

the members of Holy Trinity Church were also opposed to cruel sports

and gambling, worked for prison reform, and sponsored several

missionaries at home and overseas.

xxxxxThe trade in

West African slaves was begun by the Portuguese as early as 1444,

during their expeditions along the west coast of Africa. The Trans-

xxxxxThe trade in

West African slaves was begun by the Portuguese as early as 1444,

during their expeditions along the west coast of Africa. The Trans-

xxxxxIn Britain, the Quakers had campaigned against the slave

trade for many years, and had presented petitions to Parliament in

1783 and 1787. However, the first positive step was taken in 1787

with the establishment of the Society for

the Abolition of the Slave Trade. It was

formed by the English philanthropist Granville

Sharp (1735-

xxxxxIn Britain, the Quakers had campaigned against the slave

trade for many years, and had presented petitions to Parliament in

1783 and 1787. However, the first positive step was taken in 1787

with the establishment of the Society for

the Abolition of the Slave Trade. It was

formed by the English philanthropist Granville

Sharp (1735- xxxxxBut Wilberforce and his associates continued their

struggle. The bill fell again in 1804 and 1805, but with the news

that Napoleon was opposed to the emancipation of slaves, the mood

changed. In February 1807 Parliament

outlawed the slave trade by a huge majority, 114 to 15. The Act

provided for the search and seizure of ships thought to be involved

in such business, and it sanctioned payment for the liberation of

slaves. Slavery remained a fact in British colonies, but it was seen

as the first step on the road to the complete abolition of slavery

as such. At the Congress of Vienna in 1814 a number of countries

followed Britain’s lead, though a few, like Denmark in 1792, had

adopted such measures many years earlier. It was to be some time,

however, before this particularly vile trade had been banned by all

European countries and -

xxxxxBut Wilberforce and his associates continued their

struggle. The bill fell again in 1804 and 1805, but with the news

that Napoleon was opposed to the emancipation of slaves, the mood

changed. In February 1807 Parliament

outlawed the slave trade by a huge majority, 114 to 15. The Act

provided for the search and seizure of ships thought to be involved

in such business, and it sanctioned payment for the liberation of

slaves. Slavery remained a fact in British colonies, but it was seen

as the first step on the road to the complete abolition of slavery

as such. At the Congress of Vienna in 1814 a number of countries

followed Britain’s lead, though a few, like Denmark in 1792, had

adopted such measures many years earlier. It was to be some time,

however, before this particularly vile trade had been banned by all

European countries and - xxxxxAnd it was in that year, 1833, that the American Anti-

xxxxxAnd it was in that year, 1833, that the American Anti-

xxxxxAs we have seen, the English philanthropist and

politician William Wilberforce (1759-

xxxxxAs we have seen, the English philanthropist and

politician William Wilberforce (1759- abolition of the slave trade, and the reformation of manners." In

the war against slavery he became the acknowledged leader, supported

especially by the philanthropist Granville Sharp and the cleric

Thomas Clarkson.

abolition of the slave trade, and the reformation of manners." In

the war against slavery he became the acknowledged leader, supported

especially by the philanthropist Granville Sharp and the cleric

Thomas Clarkson.  xxxxxIncidentally, when the Anti-

xxxxxIncidentally, when the Anti-