xxxxxIt was in 1880, after attending the École de Beaux-Arts, that the French artist Georges Seurat began an analytical study of colour based on scientific principles. He admired the Impressionists, but he opposed their use of short brush strokes to capture the effects of changing light, and he considered that their works lacked form. The result of his research was Pointillism (or Divisionism), a method in which small dots of pure colour, when viewed together, merged into solid tones, giving the subject greater substance and enhancing the effect of overall light. His first major work, Bathing at Asnières, made some progress in that direction, but it was not until 1884, after meeting the French artist Paul Signac, that, working together, they perfected the new technique. The result was Seurat’s masterpiece of 1896, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. The figures were clearly defined - albeit rigid in form -, order was imposed, and the whole scene was bathed in a shimmering light. The work aroused a great deal of interest, and its unique style became known as Neo-Impressionism. Other works followed using the same method. These included three large works depicting Paris night life - Invitation to the Sideshow, The Can-Can, and The Circus - and some 40 smaller works. In 1891, however, at the age of 31, Seurat’s life was brought to a short and tragic end by a sudden illness, and it was left to Signac to give a lead to the new movement. It did not survive in its original form, but it did play an important part in the development of the avant-garde movements of the 20th century.

GEORGES PIERRE SEURAT 1859 - 1891 (Va, Vb, Vc)

Acknowledgements

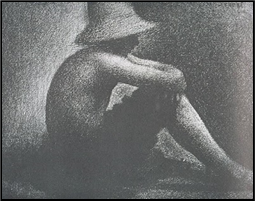

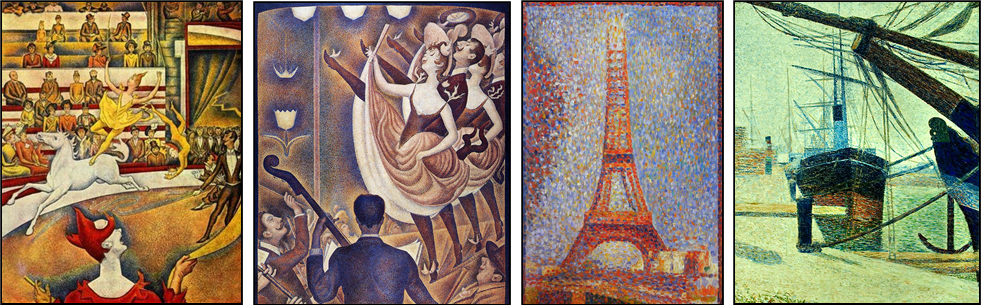

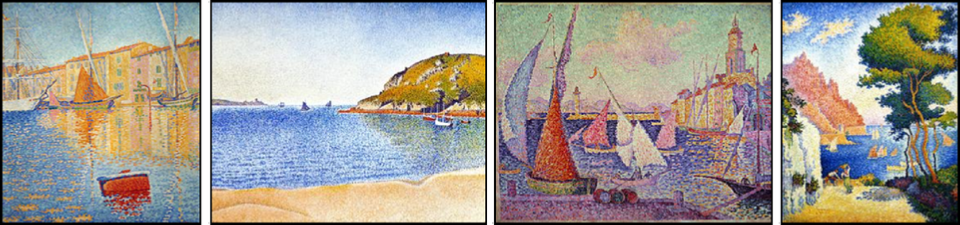

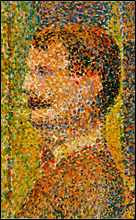

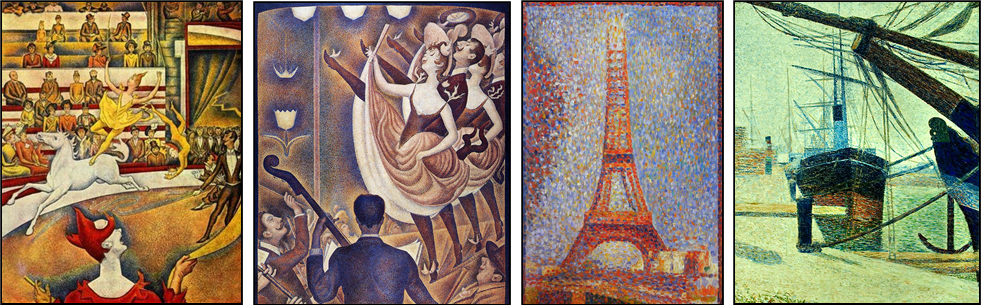

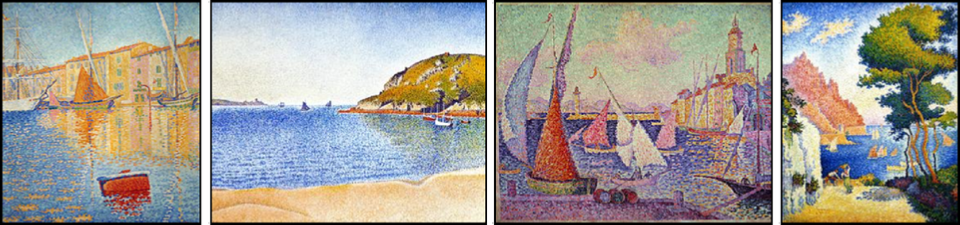

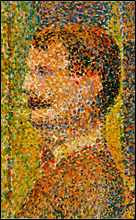

Seurat: example of Pointillism from Circus Sideshow – Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Bathers at Asnières – National Gallery, London; Ile de la Grande Jatte – The Art Institute of Chicago, IL; The Circus – Musée d’Orsay, Paris; Study for La Chahut – Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY; Eiffel Tower – Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, CA; The Harbour at Honfleur, Normandy – Rijksmuseum, Kroller-Muller, Otterlo, Netherlands; Seated Boy with Straw Hat (drawing) – Art Gallery of Yale University, New Haven, CT; Drawing of Signac – private collection. Signac: The Papal Palace, Avignon – Musée d’Orsay, Paris; Red Buoy – Musée d’Orsay, Paris; Saint-Cast – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Saint-Tropez – Musée de l’Annonciade, Saint-Tropez; Capo de Noli – Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne.

xxxxxThe French artists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac met in 1884, and it was these two painters who pioneered and promoted the colouring technique known as Pointillism (or Divisionism), an extension of Impressionism in which small dabs or flecks of pure paint replaced the traditional short brush strokes (example illustrated). Seuratxwas the chief creator of this new technique. Signac adopted it and became its main theorist. Together they initiated what came to be known as Neo-Impressionism, a method of painting which was to play an important part in the development of the avant-garde movements of 20th century.

xxxxxThe French artists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac met in 1884, and it was these two painters who pioneered and promoted the colouring technique known as Pointillism (or Divisionism), an extension of Impressionism in which small dabs or flecks of pure paint replaced the traditional short brush strokes (example illustrated). Seuratxwas the chief creator of this new technique. Signac adopted it and became its main theorist. Together they initiated what came to be known as Neo-Impressionism, a method of painting which was to play an important part in the development of the avant-garde movements of 20th century.

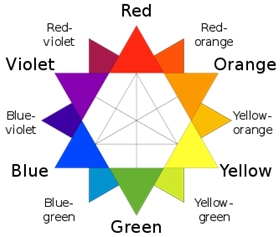

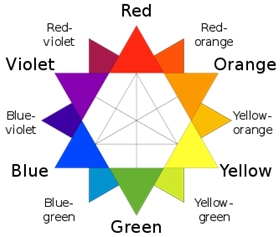

xxxxxSeurat was born into a wealthy Paris family, and showed a real talent for figure drawing at an early age. He grew up in the capital, but during the Paris Commune of 1871, when he was twelve years old, the family took refuge at Fontainebleau. He entered the École des Beaux-Arts in 1878, and over the next two years received a conventional academic training. During this time he was particularly impressed by the use made of colour by the French artist Eugène Delacroix, and by the ordered, geometrical beauty to be found in the works of the 15th century Italian painter Piero della Francesca. His interest in both was to influence his own style.  On completion of his course, Seurat was obliged to do a year’s compulsory national service - spent at Brest on the Brittany coast - but he returned to Paris in 1880, anxious to start his artistic career. It was then that, determined to push forward the frontiers of artistic knowledge, he became deeply interested in the scientific basis of art. Havingxlearnt of the theories of colour and optics put forward in contemporary treatises by the French chemist Michel Chevreul (1786-1889), and the American physicist Ogden Rood (1831-1902), he began a painstaking, analytical study of colour based on scientific principles.

On completion of his course, Seurat was obliged to do a year’s compulsory national service - spent at Brest on the Brittany coast - but he returned to Paris in 1880, anxious to start his artistic career. It was then that, determined to push forward the frontiers of artistic knowledge, he became deeply interested in the scientific basis of art. Havingxlearnt of the theories of colour and optics put forward in contemporary treatises by the French chemist Michel Chevreul (1786-1889), and the American physicist Ogden Rood (1831-1902), he began a painstaking, analytical study of colour based on scientific principles.

xxxxxNot surprisingly, he applied his findings to Impressionism - a movement specifically interested in colour and the ever-changing effects of light. He went along with the movement’s subject matter - contemporary outdoor scenes and leisure activities - but, very much like the French artist Paul Cézanne - he rejected its lack of form and, in addition, its instinctive, spontaneous approach to the application of colour and the capture of light. He considered that the rendering of colour called for a detailed understanding of how colour was formed and how it was interpreted by the human eye. Thexresult of his research was Pointillism, a method in which small dots or flecks of pure colour, when viewed together, merged into solid tones and bathed the canvas in a shimmering light. The French painter Camille Pissarro, who adopted the method for a time, called it a form of “scientific Impressionism.”

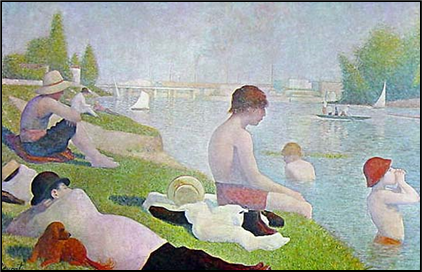

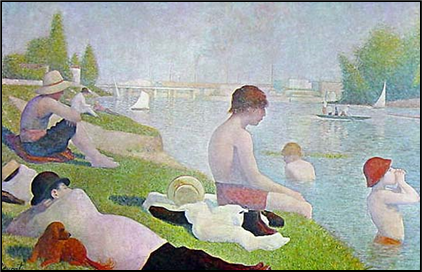

xxxxxSeurat had two portraits accepted for the official Salon in 1883 - one of his mother and the other of an artist friend named Aman-Jean - but the first hint of his experiments in colour came in 1884 when he produced a huge canvas entitled Bathing at Asnières, a scene of boys playing in the River Seine (illustrated). Predictably, this picture was refused by the Salon, and, for this reason, he took the lead in forming a Society of Independent Artists. This held its own exhibition in June of that year, and his new work could then be displayed. It caused quite a stir by its originality. Produced in his studio after long hours of outdoor preparatory work, it had nothing of the casual spontaneity associated with the Impressionists. Indeed, it provided a solidity of form and composition which was at variance with the aims of the Impressionists, and it captured to a greater extent the effect of light they sought to achieve. And it demonstrated too, by small criss-cross strokes and groups of small dots of colour, the beginnings of his new technique, yet in its early stages. The work impressed the critics by its shimmering, vibrant light, but there was little if any suggestion of movement, the figures were statuesque, and the whole scene appeared frozen in time, despite the warmth of its subject.

xxxxxSeurat had two portraits accepted for the official Salon in 1883 - one of his mother and the other of an artist friend named Aman-Jean - but the first hint of his experiments in colour came in 1884 when he produced a huge canvas entitled Bathing at Asnières, a scene of boys playing in the River Seine (illustrated). Predictably, this picture was refused by the Salon, and, for this reason, he took the lead in forming a Society of Independent Artists. This held its own exhibition in June of that year, and his new work could then be displayed. It caused quite a stir by its originality. Produced in his studio after long hours of outdoor preparatory work, it had nothing of the casual spontaneity associated with the Impressionists. Indeed, it provided a solidity of form and composition which was at variance with the aims of the Impressionists, and it captured to a greater extent the effect of light they sought to achieve. And it demonstrated too, by small criss-cross strokes and groups of small dots of colour, the beginnings of his new technique, yet in its early stages. The work impressed the critics by its shimmering, vibrant light, but there was little if any suggestion of movement, the figures were statuesque, and the whole scene appeared frozen in time, despite the warmth of its subject.

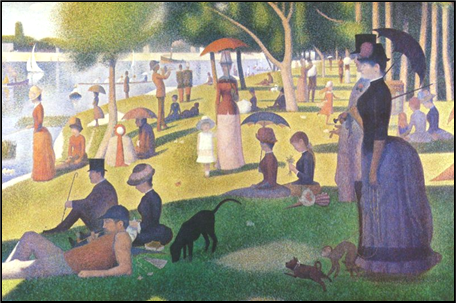

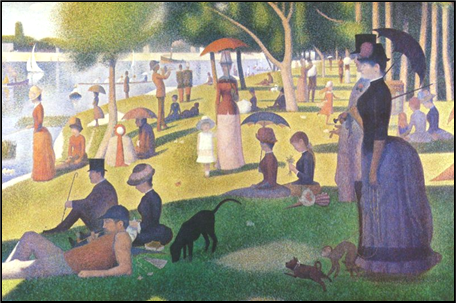

xxxxxIt was in 1884, at the first meeting of the Independent Artists, that Seurat met Paul Signac, the man who was to become his chief disciple. He readily embraced the novel ideas being put forward by Seurat and made his own contribution. Together they took the idea of pointillism a significant step forward by studying the more intensive effect that could be achieved by the arrangement of the three primary colours and their complements. To put this revolutionary method to the test Seurat then embarked upon another large, outdoor scene, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, a park alongside the River Seine. He spent most of 1885 preparing for this work, producing over 200 drawings and oil sketches outdoors, but completing it in his studio. The following year, at the invitation of Pissarro, it was shown at the Impressionists’ eighth and last exhibition, held in Paris.

xxxxxThis original work (illustrated) provided not only the perfect example of pointillism - the creation of a vibrant, luminous light by means of a scientific application of colour - but it created too, by its harmonious, geometric formation and its impassive approach, a dignified, silent and somewhat eerie snap-portrayal of what was, in fact, a simple scene in a park. It resembled an ancient sculptured frieze, beautiful to behold but frozen in time. As such, it aroused a great deal of interest and attracted a certain amount of harsh criticism but, given time, it captured the imagination of the art world. Itxwas soon on general exhibition in Paris and New York, and the young French critic Félix Fénéon (1861-1944) praised the work, coining the term Neo-Impressionism to describe this new departure in art.

xxxxxThis original work (illustrated) provided not only the perfect example of pointillism - the creation of a vibrant, luminous light by means of a scientific application of colour - but it created too, by its harmonious, geometric formation and its impassive approach, a dignified, silent and somewhat eerie snap-portrayal of what was, in fact, a simple scene in a park. It resembled an ancient sculptured frieze, beautiful to behold but frozen in time. As such, it aroused a great deal of interest and attracted a certain amount of harsh criticism but, given time, it captured the imagination of the art world. Itxwas soon on general exhibition in Paris and New York, and the young French critic Félix Fénéon (1861-1944) praised the work, coining the term Neo-Impressionism to describe this new departure in art.

xxxxxLa Grande Jatte, the second of his large canvases, is regarded today as Seurat’s masterpiece and, over the years, it has earned an iconic status in the art world, but its unique style can be readily identified in the paintings he produced over the next four years. These included four large-scale works, The Models (a study of female nudes) and three depicting Paris nightlife, An Invitation to the Sideshow, The Can-Can (poster-like with a hint of movement) and his final work The Circus. Among his smaller works, some 40 in number, were Bridge at Courbevoie, The Eiffel Tower, and numerous views of the Normandy coast and the area around Gravelines, painted during the summer months. His portraits included one of Signac, and one of his mistress under the title A Young Woman Holding a Powder-puff.

Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc-1881-1901-Vc

xxxxxAs we have seen, the French artist Paul Signac (1863-1935) met George Seurat in 1884 and became his chief disciple and theorist. Working together they pioneered the colouring technique known as Pointillism. By this method the short brush strokes of the Impressionists were replaced by small dots of pure colour which, when viewed together, merged into solid tones and bathed the subject in a shimmering light. He worked tirelessly to convert others to this new art form - dubbed Neo-Impressionism - and in 1899 explained the scientific theory of colour upon which pointillism was based in a book entitled From Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism. He produced a large number of landscapes and seascapes, many of which were water colours, and these became noted for their vibrant colours and the way they captured the movement of water and clouds. Among his works which best demonstrated pointillism are The Red Buoy, The Storm, Saint Tropez, and Sails and Pines, all produced in the 1890s. His outstanding skill as a colourist can be seen in his The Papal Palace at Avignon. As in the case of Seurat, his works played an important part in the development of 20th century art.

xxxxxThe French artist Paul Signac (1863-1935), as we have seen, met Georges Seurat in 1884, at the founding of the Society of Independent Artists. An admirer of the works of the Impressionists, particularly Claude Monet, he nonetheless valued pointillism as an extension of Impressionism, and made a major contribution towards its development and general acceptance. He maintained that this new art form, Neo-Impressionism, by its exclusive use of optical mixtures of pure colours, ensured, in his own words, “a maximum luminosity of colour intensity and of harmony - a result that has never yet been obtained.” There was no place for “muddy mixtures”. And in 1899, in his book From Delacroix to Neo- Impressionism, he provided a detailed exposition of the scientific theory of colours upon which Pointillism was based. (The portrait here is a sketch in conté crayon by Seurat, produced in 1890.)

xxxxxThe French artist Paul Signac (1863-1935), as we have seen, met Georges Seurat in 1884, at the founding of the Society of Independent Artists. An admirer of the works of the Impressionists, particularly Claude Monet, he nonetheless valued pointillism as an extension of Impressionism, and made a major contribution towards its development and general acceptance. He maintained that this new art form, Neo-Impressionism, by its exclusive use of optical mixtures of pure colours, ensured, in his own words, “a maximum luminosity of colour intensity and of harmony - a result that has never yet been obtained.” There was no place for “muddy mixtures”. And in 1899, in his book From Delacroix to Neo- Impressionism, he provided a detailed exposition of the scientific theory of colours upon which Pointillism was based. (The portrait here is a sketch in conté crayon by Seurat, produced in 1890.)

xxxxxLike Seurat, Signac was born into a rather wealthy Paris family. He first showed an interest in architecture, but at the age of 18, having come to admire the work of the Impressionists, he decided to become an artist. Whilst he readily adopted pointillism in 1884 and worked tirelessly to promote this new art form - a colouring technique whereby small dabs of pure pigment replaced the short brush strokes - he remained an Impressionist at heart, anxious to capture movement and the changing effects of light. Furthermore, by introducing larger dots of paint and his mosaic-like squares of colour, he moved somewhat away from the more rigid format introduced by Seurat.

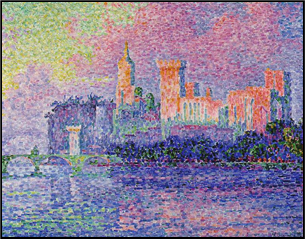

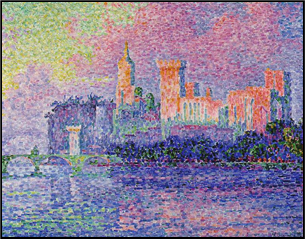

xxxxxDuring a busy career, Signac produced some striking landscapes and, as a keen sailor, a large number of splendid seascapes depicting the coasts of Normandy, Brittany and the Mediterranean. He proved particularly successful in capturing the movement of water and clouds. In his later years he turned to painting scenes of Paris and other French cities. His adherence to pointillism can best be seen in his earlier works, such as Red Buoy, Saint-Cast, Saint-Tropez, and Capo de Noli, all produced in the 1890s and illustrated below. Impressive, too, is his The Papal Palace at Avignon (illustrated here), affirming his skill as a colourist, and a remarkable portrait of the critic Félix Fénéon, set against the swirling lines of an abstract collage. Like Seurat, these works played an important part in the development of 20th century art.

xxxxxDuring a busy career, Signac produced some striking landscapes and, as a keen sailor, a large number of splendid seascapes depicting the coasts of Normandy, Brittany and the Mediterranean. He proved particularly successful in capturing the movement of water and clouds. In his later years he turned to painting scenes of Paris and other French cities. His adherence to pointillism can best be seen in his earlier works, such as Red Buoy, Saint-Cast, Saint-Tropez, and Capo de Noli, all produced in the 1890s and illustrated below. Impressive, too, is his The Papal Palace at Avignon (illustrated here), affirming his skill as a colourist, and a remarkable portrait of the critic Félix Fénéon, set against the swirling lines of an abstract collage. Like Seurat, these works played an important part in the development of 20th century art.

xxxxxIllustrated here (left to right) are: The Circus, La Chahut, The Eiffel Tower, and The Harbour at Honfleur, Normandy.

xxxxxWhilst admiring the work of the Impressionists, their choice of subject matter and their fascination with the changing effects of light, Seurat was opposed to what he saw as their spontaneous, casual approach. He sought to put their treatment of light onto a firm scientific basis by means of his “optic mixture” and, at the same time, to give his chosen scene a greater degree of form and clarity. This he achieved, albeit in a somewhat stilted, geometric manner. In so doing he inaugurated Neo-Impressionism, a movement which, though brief in its existence, was to influence progressive contemporaries like Degas, Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Toulouse Lautrec, and to play an important part in the evolution of 20th century art in general. Indeed, by his intellectual, studied approach to painting he can be seen as the precursor of what is described today as “Modern Art”.

xxxxxSeurat’s life was brought to a short and tragic end in 1891. He contracted a fatal disease -possibly meningitis or diphtheria - and died in Paris on Easter Sunday at the age of 31. He was buried in the family vault at the city’s Père Lachaise Cemetery.

xxxxxIncidentally, Seurat knew all the major French artists of his day but, as a quiet, refined man by nature, he made few close friends. Always well dressed - Edgar Degas dubbed him “the notary” -, he took his work seriously and showed great powers of perseverance and concentration. He was also very secretive. None knew of his liaison with a young woman of 21 named Madeleine Knobloch, nor of the boy she bore him in February 1890. It was not until two days before his death that his family learnt of his mistress and son. Sadly the boy, Pierre Georges, died two weeks after Seurat’s death, having contracted his father’s illness. ……

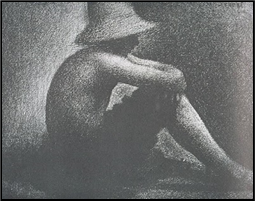

xxxxx…… Seuratxwasxalso an exceptional draughtsman. He produced some 500 drawings and many were executed with conté crayon on rough paper, a method which was ideal for detailed hatched work and subtle changes of tone. The conté crayon, made with powdered graphite or chalk and mixed with wax, was invented by the French artist Nicolas-Jacques Conté (1755-1805) in 1795. He was also a hot-air balloonist, and made a number of flights while serving under Napoleon in Egypt in 1798. ……

xxxxx…… InxFebruary 1888, Seurat, together with Signac, visited Brussels to attend a private viewing of Les Vingt (The Twenty), a small group of independent artists which included Paul Cézanne, Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. He showed seven canvases, including La Grande Jatte and Le Chahut, and impressed the group’s members by his colour technique.

xxxxxIncidentally, apart from oil paintings Signac produced a large number of water colours, etchings, lithographs and pen and ink sketches, many of which were in the pointillist manner. Indeed, the majority of his seascapes were water colours, sketched rapidly and noted for their vibrant colours. ……

xxxxx…… Apart from his voyages along the French coastline, Signac made a tour of Italy in 1890, and two visits to Venice and London in the early years of the 20th century. He visited Van Gogh at Arles in 1889, and his outgoing personality - in contrast to Seurat’s reserved nature – gained him friends among many of the other avant-garde artists of the day.

xxxxxThe French artists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac met in 1884, and it was these two painters who pioneered and promoted the colouring technique known as Pointillism (or Divisionism), an extension of Impressionism in which small dabs or flecks of pure paint replaced the traditional short brush strokes (example illustrated). Seuratxwas the chief creator of this new technique. Signac adopted it and became its main theorist. Together they initiated what came to be known as Neo-

xxxxxThe French artists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac met in 1884, and it was these two painters who pioneered and promoted the colouring technique known as Pointillism (or Divisionism), an extension of Impressionism in which small dabs or flecks of pure paint replaced the traditional short brush strokes (example illustrated). Seuratxwas the chief creator of this new technique. Signac adopted it and became its main theorist. Together they initiated what came to be known as Neo- On completion of his course, Seurat was obliged to do a year’s compulsory national service -

On completion of his course, Seurat was obliged to do a year’s compulsory national service - xxxxxSeurat had two portraits accepted for the official Salon in 1883 -

xxxxxSeurat had two portraits accepted for the official Salon in 1883 - xxxxxThis original work (illustrated) provided not only the perfect example of pointillism -

xxxxxThis original work (illustrated) provided not only the perfect example of pointillism - xxxxxThe French artist Paul Signac (1863-

xxxxxThe French artist Paul Signac (1863- xxxxxDuring a busy career, Signac produced some striking landscapes and, as a keen sailor, a large number of splendid seascapes depicting the coasts of Normandy, Brittany and the Mediterranean. He proved particularly successful in capturing the movement of water and clouds. In his later years he turned to painting scenes of Paris and other French cities. His adherence to pointillism can best be seen in his earlier works, such as Red Buoy, Saint-

xxxxxDuring a busy career, Signac produced some striking landscapes and, as a keen sailor, a large number of splendid seascapes depicting the coasts of Normandy, Brittany and the Mediterranean. He proved particularly successful in capturing the movement of water and clouds. In his later years he turned to painting scenes of Paris and other French cities. His adherence to pointillism can best be seen in his earlier works, such as Red Buoy, Saint-