xxxxxAs noted in 1644 (C1) when reading about Matthew Hopkins, the English Witch-Finder General, the alleged worship of the devil did not become a burning issue in Europe until the 15th century. It was then that the Pope issued a bull condemning witchcraft, and this gave way to a vicious period of witch hunting. Thousands were sentenced to death or given cruel punishments. This witch hunt mania eventually reached the American colonies. Here, following a frenzy of accusations, a sensational series of trials were held at the town of Salem, Massachusetts in 1692. Before the hysteria had subsided, 150 had been put on trial, nineteen had been executed, and many had been imprisoned. Later, in 1697, one of the judges, Samuel Sewall, bravely confessed that his decisions had been made in error.

THE SALEM WITCH TRIALS 1692 (W3)

Acknowledgements

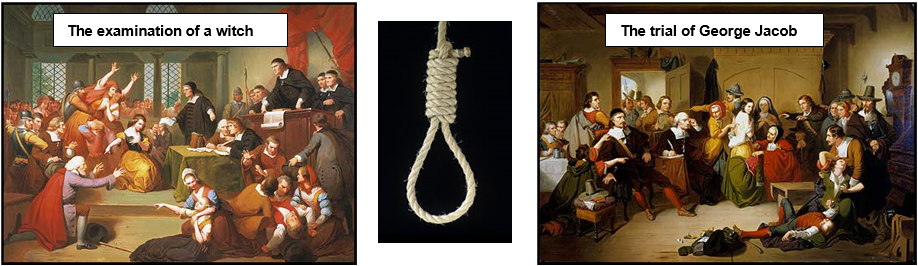

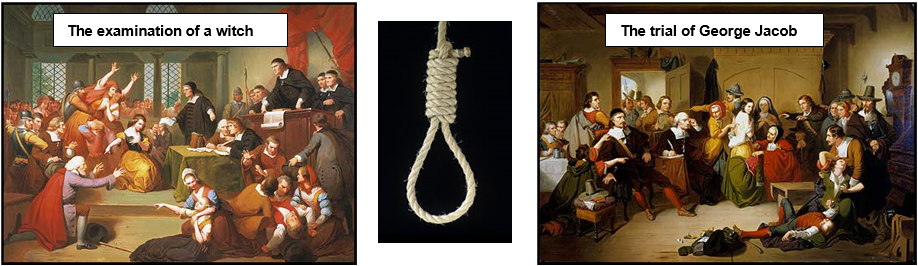

Burning: woodcut, c1580, market place in Guernsey, artist unknown. Examination: by the American artist Tompkins Harrison Matteson (1813-1884) – Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts. Trial: by the American artist Tompkins Harrison Matteson (1813-1884) – Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts. Sewall: by the Scottish/American artist John Smybert (1688-1751), 1729 – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts.

xxxxxAs explained in our study of Matthew Hopkins, the English Witch-Finder General, in 1644 (C1), the "black art" associated with witches and sorcerers was widely practised in ancient times, but the worship of the devil (as it came to be regarded) did not become a burning issue in medieval Europe until the 15th century. It was then that the Church evoked the Old Testament script "Thou shall not suffer a sorceress to live" (Exodus 22:18), and the persecution of witches began in earnest.

xxxxxAs explained in our study of Matthew Hopkins, the English Witch-Finder General, in 1644 (C1), the "black art" associated with witches and sorcerers was widely practised in ancient times, but the worship of the devil (as it came to be regarded) did not become a burning issue in medieval Europe until the 15th century. It was then that the Church evoked the Old Testament script "Thou shall not suffer a sorceress to live" (Exodus 22:18), and the persecution of witches began in earnest.

xxxxxThe first witch hunt of any size took place in Switzerland in 1427, but it was not until some sixty years later that Pope Innocent VIII issued his bull condemning witchcraft (Summis Desiderantes), and appointed two Dominican friars, Johann Sprenger and Heinrich Kraemer, to stamp it out. Their book, The Witches' Hammer (Malleus Maleficarium), published in 1486, prescribed the many and varied evil acts practised by those possessed of the devil, and gave rise to a vicious period of witch hunting hysteria. Those accused were subjected to a number of "tests", and those found guilty - often after being tortured - were cruelly punished or condemned to death by hanging or burning.

xxxxxThe first witch hunt of any size took place in Switzerland in 1427, but it was not until some sixty years later that Pope Innocent VIII issued his bull condemning witchcraft (Summis Desiderantes), and appointed two Dominican friars, Johann Sprenger and Heinrich Kraemer, to stamp it out. Their book, The Witches' Hammer (Malleus Maleficarium), published in 1486, prescribed the many and varied evil acts practised by those possessed of the devil, and gave rise to a vicious period of witch hunting hysteria. Those accused were subjected to a number of "tests", and those found guilty - often after being tortured - were cruelly punished or condemned to death by hanging or burning.

xxxxxFor the next eighty years or so - the height of the hunting season - trials were held throughout Western Europe, the vast majority ending in death sentences. In England, for example, Matthew Hopkins, the self-styled "Witch-Finder General", earned a good living by conducting a campaign in eastern England. He sentenced some 200 people to death - mostly women - in the space of three years. In Scotland, a total of 1,350 were burned at the stake during this period, and in south-west Germany alone some 3,000 were executed. It was not until around 1680 that the validity of these trials began to be questioned and there was a sharp decline in their number.

W3-1688-1702-W3-1688-1702-W3-1688-1702-W3-1688-1702-W3-1688-1702-W3-1688-1702-W3

xxxxxBy then, however, the witch hunt mania had reached European settlements within the Americas. Of the trials conducted here, the most sensational were those held in the town of Salem in Massachusetts in 1692. Here, a series of voodoo tales, told by a West-Indian slave named Tituba, whipped up a frenzy of accusations. Initially three women were accused of witchcraft, including Tituba herself, but within the space of a few months, false confessions and counter charges resulted in no less than 150 people facing trial, including the wife of the state governor. With the encouragement of the Church, three court judges were appointed and, amid widespread mass hysteria, condemned nineteen to death and many others to terms of imprisonment. By September, however, the frenzy had subsided and the mood of the public had changed dramatically. The trials were condemned, and the following month Governor Sir William Phips dissolved the special court and released the remaining prisoners. Later, all the convictions were annulled, and indemnities were granted to the families of those who had been hanged.

xxxxxTo his credit, one of the trial judges, Samuel Sewall (1652-1730), later admitted that his decisions had been made in error, and in 1697 he stood in the Old South Church in Boston while his confession of guilt was read out in public. A man of compassion, he was at one time commissioner of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England. His writings included The Selling of Joseph, an early appeal against slavery, and A Memorial Relating to the Kennebeck Indians, a work in which he argued for the humane treatment of the American Indian.

xxxxxIncidentally, a Boston congregational minister by the name of Increase Mather (1639-1723) may well have contributed to the public fervour which surrounded the Salem trials. In 1684 he published his An Essay for the Recording of Illustrious Providencies. Describing as it did the timely hand of divine providence in rescuing people from supernatural as well as natural disasters, it possibly played a part a few years later in whipping up the inordinate fear of witchcraft within the local communities. ......

xxxxx...... In England, the death penalty for witchcraft was abolished in 1746, and the last legal execution of a witch was recorded in Switzerland in 1782. Witchcraft and like practices are still to be found today, notably in countries of South East Asia, Africa, Latin America and isolated areas in the United States.

xxxxxAs explained in our study of Matthew Hopkins, the English Witch-

xxxxxAs explained in our study of Matthew Hopkins, the English Witch- xxxxxThe first witch hunt of any size took place in Switzerland in 1427, but it was not until some sixty years later that Pope Innocent VIII issued his bull condemning witchcraft (Summis Desiderantes), and appointed two Dominican friars, Johann Sprenger and Heinrich Kraemer, to stamp it out. Their book, The Witches' Hammer (Malleus Maleficarium), published in 1486, prescribed the many and varied evil acts practised by those possessed of the devil, and gave rise to a vicious period of witch hunting hysteria. Those accused were subjected to a number of "tests", and those found guilty -

xxxxxThe first witch hunt of any size took place in Switzerland in 1427, but it was not until some sixty years later that Pope Innocent VIII issued his bull condemning witchcraft (Summis Desiderantes), and appointed two Dominican friars, Johann Sprenger and Heinrich Kraemer, to stamp it out. Their book, The Witches' Hammer (Malleus Maleficarium), published in 1486, prescribed the many and varied evil acts practised by those possessed of the devil, and gave rise to a vicious period of witch hunting hysteria. Those accused were subjected to a number of "tests", and those found guilty -