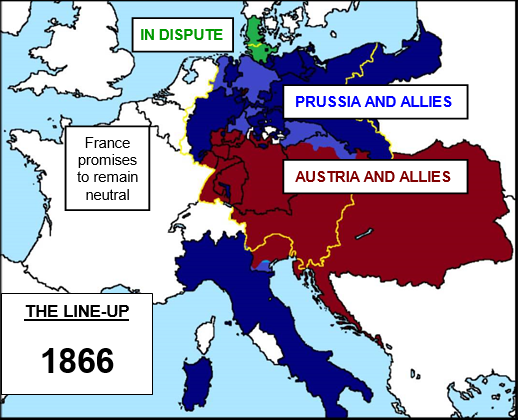

xxxxxAs we have seen, the settlement at the end of the Second Schleswig War of 1864, engineered by the Prussian foreign minister Otto von Bismarck, provided a ready excuse for war against Austria in 1866. Bismarck was anxious to exclude Austria from German affairs so that Prussia could lead the struggle for German unification. Having received a promise of neutrality from Napoleon III of France, and gained the military support of Italy, Prussia conjured up a dispute over Austria’s administration of Holstein and invaded the duchy in early June. Within a matter of days Austria and the majority of German states had declared war on Prussia and its ally Italy. The Battle of Sadowa (also known as the Battle of Koniggratz) proved the decisive encounter at the beginning of July. Both sides fought hard, but Prussia’s highly-

THE AUSTRO -

(OR SEVEN WEEKS’ WAR) 1866 (Vb)

Acknowledgements

Map (Central Europe): licensed under Creative Commons – https://en.wiki2.org/wiki/Austro-

xxxxxAs we have seen, a plausible excuse for a war with Austria had been conjured up by the Prussian foreign minister Otto von Bismarck two years earlier by means of the peace settlement which ended the Second Schleswig War in 1864. This arrangement, whereby Prussia gained Schleswig and Austria was ceded Holstein, produced an uneasy, almost unworkable situation which, when so required, could be readily exploited by Bismarck to provoke a war between the two countries. Since the formation of the German Confederation, established by the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Austria had been the dominant power in the affairs of Germany, but the rise of Prussia had brought a rival onto the scene. As early as 1850, in fact, Frederick William IV of Prussia had attempted to establish his own confederation of German states, but had been forced by Austria to abandon the idea by a treaty dubbed “the humiliation of Olmutz”. By 1866, however, Bismarck felt confident that Prussia had the military capability to wage a successful war against the Austrians and to force them out of the Confederation -

military capability to wage a successful war against the Austrians and to force them out of the Confederation -

xxxxxBut before taking on the considerable might of the Austrian Empire, Bismarck needed to take steps to minimise any possible opposition and to summon up support. He was confident that neither Britain nor Russia would come to the aid of Austria in the short term, but he feared French intervention. For this reason he met Napoleon III at Biarritz in October 1865 and, according to some accounts, received a guarantee of French neutrality in the event of an Austro-

xxxxxHowever, the secret agreement made with Italy was only valid for three months so Bismarck could waste no time in finding an excuse for war. In May, therefore, Prussia proposed reforms of the Confederation which were clearly aimed at reducing Austrian influence, and then openly criticised the way in which the Austrians were managing their administration of Holstein. When the Austrians responded on June 1st by asking the Federal Diet to review the future of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, this action gave Bismarck his casus belli -

xxxxxHowever, the secret agreement made with Italy was only valid for three months so Bismarck could waste no time in finding an excuse for war. In May, therefore, Prussia proposed reforms of the Confederation which were clearly aimed at reducing Austrian influence, and then openly criticised the way in which the Austrians were managing their administration of Holstein. When the Austrians responded on June 1st by asking the Federal Diet to review the future of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, this action gave Bismarck his casus belli -

xxxxxTo counter the forces of the German Confederation, a Prussian force known as the Army of the Main was despatched to Bavaria, and met up with an Hanovarian army near the town of Langensalza in the last week of June. In the battle that followed the Hanovarians won the opening rounds, but with the arrival of reinforcements the Prussians surrounded the Hanovarians and forced them to surrender. This virtually marked an end to resistance by Confederate forces, though the Saxon army did fight alongside the Austrians. In the meantime a large Prussian force of some 250,000 men, moved rapidly by road and rail, entered Bohemia, the major area of operations. After early skirmishes, during which the Prussian needle rifle caused heavy casualties, the two sides met near the village of Sadowa, close to the town of Koniggratz on the River Elbe.

xxxxxThe Battle of Sadowa (or Battle of Koniggratz) opened on the 3rd July with neither side having good defensive positions. General Moltke, the Prussian commander, instructed to gain a speedy victory, planned to use his three armies in unison to overwhelm the Austrians in the centre of their line and on both flanks. In a dawn attack, his First Army advanced successfully in the centre, capturing Sadowa, and his Elbe army made progress against the enemy’s left flank, despite heavy and concentrated artillery fire. However, the failure of his powerful Second Army to take part in the coordinated attack from the north-

xxxxxThe Battle of Sadowa (or Battle of Koniggratz) opened on the 3rd July with neither side having good defensive positions. General Moltke, the Prussian commander, instructed to gain a speedy victory, planned to use his three armies in unison to overwhelm the Austrians in the centre of their line and on both flanks. In a dawn attack, his First Army advanced successfully in the centre, capturing Sadowa, and his Elbe army made progress against the enemy’s left flank, despite heavy and concentrated artillery fire. However, the failure of his powerful Second Army to take part in the coordinated attack from the north-

xxxxxThe Austrians were more successful in their war against Italy. They were defeated at the Battle of Bezzecca by a force led by the Italian freedom fighter Giuseppe Garibaldi, but their army of the south gained a decisive victory over Italian regular troops at the Battle of Custoza, fought 12 miles south-

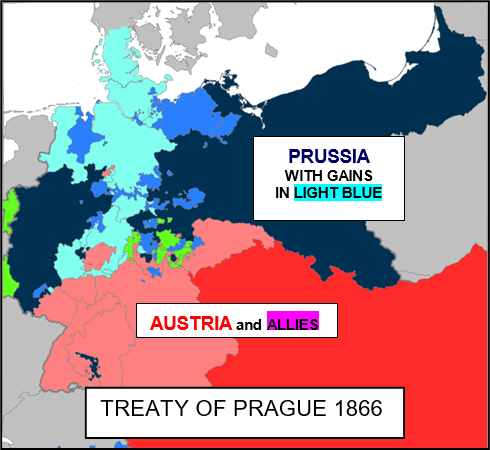

xxxxxWithxthe conflict between Prussia and Austria resolved in a matter of weeks, Bismarck was anxious to make a settlement which, like the war itself, had strictly limited objectives. By the Treaty of Prague in August 1866 Austria was totally excluded from taking any part in German affairs, but, save for this, there was no talk of a military occupation, and Austria was permitted to keep all its possessions with the exception of Venetia -

xxxxxWithxthe conflict between Prussia and Austria resolved in a matter of weeks, Bismarck was anxious to make a settlement which, like the war itself, had strictly limited objectives. By the Treaty of Prague in August 1866 Austria was totally excluded from taking any part in German affairs, but, save for this, there was no talk of a military occupation, and Austria was permitted to keep all its possessions with the exception of Venetia -

For its part, Prussia annexed the states of Hanover, Hesse-

xxxxxBy replacing Austria as the principal German power, Prussia emerged as a serious rival to France. As we shall see, the Franco- mpire, and a totally new balance of power on the continent of Europe.

mpire, and a totally new balance of power on the continent of Europe.

xxxxxIncidentally, the personal union of Hanover with the United Kingdom ended in 1837 with the reign of Queen Victoria (because Hanover could only be inherited by males), but Prussia’s annexation of Hanover in 1867 severed the connection the British royal family had had with the House of Hanover (coat of arms illustrated) since the beginning of the reign of George I in 1714. This, plus the establishment of the German Empire a few years later, created a strain in Anglo-

Including:

The Battles of

Sadowa and Custoza

Vb-