xxxxxOn his return to power in 1815 Louis XVIII saw the need to play the constitutional monarch. His charter established a parliament, introduced legal and social reforms, granted greater press freedom, and extended the franchise. However, the murder of the Duke de Berry (son of the future Charles X) in 1820 brought a violent reaction by the ultra-royalists (or “Ultras), and Louis was obliged to introduce measures in favour of the nobility and the church, and to cut back on the liberal reforms. With the succession of his brother, Charles X, in 1824, a fervent ultra-royalist, this trend quickly gathered pace. He continued to undermine the liberal rights and institutions whilst reviving the Church, sanctioning the return of the Jesuits, and compensating the emigrés for their loss of land. Matters came to a head in 1830 when he dissolved the legislature, and suspended the freedom of the press to stifle opposition. Rebellion broke out across Paris, and in three days the city was in the hands of the republicans and constitutional monarchists. The latter, supported by the former general La Fayette and the statesman Adolphe Thiers, won their way, and Louis Philippe, Duc d’Orleans, was persuaded to accept the Crown. Charles X abdicated and fled the country. Louis Philippe agreed to be a constitutional monarch, but his reign did not fulfil its early promise and, as we shall see, he was likewise overthrown in 1848 (Va), Europe’s Year of Revolutions. The July Revolution of 1830 sparked off rebellions across Europe in 1831, but not all were as successful.

xxxxxWhen Louis XVIII of Franc e eventually regained his throne following the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, he faced a daunting task. If his dynasty were to survive he had to find some way of satisfying the demands of the ultra-royalists, wanting the re-establishment of an absolute monarchy (and returning home to get it), and, at the same time, of meeting the liberal aspirations born of the French Revolution. In the opening years of his reign, during which the ultra-royalists (or “Ultras”) and the Republicans indulged in reprisals against each other, he saw the need to play the constitutional monarch, cautiously accepting to a large extent the extraordinary rights won by the common people via the Revolution and, to a lesser extent, Napoleon. He realised that to do otherwise would invite a return to rebellion and anarchy. Thus the Charter he put forward in 1814 established a parliamentary monarchy, introduced legal and social reforms, granted a greater degree of press freedom, and extended the right to vote on the basis of property ownership - though this amounted to a total of less than 100,000 voters. And two years later he was advocating a further extension of the franchise and an even greater degree of press freedom.

e eventually regained his throne following the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, he faced a daunting task. If his dynasty were to survive he had to find some way of satisfying the demands of the ultra-royalists, wanting the re-establishment of an absolute monarchy (and returning home to get it), and, at the same time, of meeting the liberal aspirations born of the French Revolution. In the opening years of his reign, during which the ultra-royalists (or “Ultras”) and the Republicans indulged in reprisals against each other, he saw the need to play the constitutional monarch, cautiously accepting to a large extent the extraordinary rights won by the common people via the Revolution and, to a lesser extent, Napoleon. He realised that to do otherwise would invite a return to rebellion and anarchy. Thus the Charter he put forward in 1814 established a parliamentary monarchy, introduced legal and social reforms, granted a greater degree of press freedom, and extended the right to vote on the basis of property ownership - though this amounted to a total of less than 100,000 voters. And two years later he was advocating a further extension of the franchise and an even greater degree of press freedom.

xxxxxAfter a shaky start these measures produced a workable legislature and a climate favourable to commercial and industrial expansion. Furthermore, foreign occupation came to an end in 1818, and France took its place again amongst the great powers of Europe. But in 1820, with the assassination of the Duke de Berry (son of the future Charles X) there was a violent Royalist reaction, and Louis was virtually forced to approve measures in favour of the nobility and the Church. The franchise was severely restricted, freedom of the press suspended, and education was put into the hands of the clergy.

xxxxxWith the death of Louis in September 1824, his younger brother, the Comte d'Artois, an ultra royalist, came to the throne as Charles X (illustrated) and confrontation became inevitable. A staunch supporter of the aristocracy and clergy, he compensated the emigrés for their loss of land during the Revolution, worked to revive the Church, and sanctioned the return of the Jesuits. At the same time, he at once set about undermining the liberal institutions and the popular rights which had been achieved by the Revolution and shrewdly tolerated by Louis. In particular, he saw freedom of the press, and the liberal opposition in the Chamber of Deputies, as a direct threat to society in general and to his dynasty in particular. He is recorded as saying that he would “rather chop wood than reign after the fashion of the King of England”!

xxxxxWith the death of Louis in September 1824, his younger brother, the Comte d'Artois, an ultra royalist, came to the throne as Charles X (illustrated) and confrontation became inevitable. A staunch supporter of the aristocracy and clergy, he compensated the emigrés for their loss of land during the Revolution, worked to revive the Church, and sanctioned the return of the Jesuits. At the same time, he at once set about undermining the liberal institutions and the popular rights which had been achieved by the Revolution and shrewdly tolerated by Louis. In particular, he saw freedom of the press, and the liberal opposition in the Chamber of Deputies, as a direct threat to society in general and to his dynasty in particular. He is recorded as saying that he would “rather chop wood than reign after the fashion of the King of England”!

xxxxxThe events which brought matters to a head came about in 1830. In March, when the Chamber of Deputies demanded the dismissal of a number of the king’s ministers, Charles dissolved the legislature, declared the new elections null and void, and followed this up in July with a complete suspension of the freedom of the press. Such repressive measures aroused widespread opposition and violent resistance in Paris. Barricades were erected in the main thoroughfares, manned by students, workers and the petty bourgeoisie, and after three days of strikes and street fighting - Les Trois Glorieuses -, Paris was in the hands of the insurgents, the republicans on the one hand and the constitutional monarchists on the other. The latter, supported by the general the Marquis de Lafayette and the statesman Adolphe Thiers, won their way, and Louis Philippe, Duc d’Orleans, was persuaded to accept the crown. Charles, deserted by all but a few, and aware that further resistance was pointless, abdicated at the beginning of August and fled to England, where he had spent much of his time during the Revolution.

xxxxxThe events which brought matters to a head came about in 1830. In March, when the Chamber of Deputies demanded the dismissal of a number of the king’s ministers, Charles dissolved the legislature, declared the new elections null and void, and followed this up in July with a complete suspension of the freedom of the press. Such repressive measures aroused widespread opposition and violent resistance in Paris. Barricades were erected in the main thoroughfares, manned by students, workers and the petty bourgeoisie, and after three days of strikes and street fighting - Les Trois Glorieuses -, Paris was in the hands of the insurgents, the republicans on the one hand and the constitutional monarchists on the other. The latter, supported by the general the Marquis de Lafayette and the statesman Adolphe Thiers, won their way, and Louis Philippe, Duc d’Orleans, was persuaded to accept the crown. Charles, deserted by all but a few, and aware that further resistance was pointless, abdicated at the beginning of August and fled to England, where he had spent much of his time during the Revolution.

xxxxxOn August 9th Louis Philippe (1773-1850), head of the house of Bourbon-Orleans, a branch of the French royal family, was proclaimed “king of the French by the grace of God and the will of the nation”. An arch liberal by royal standards, he had supported the French Revolution at its beginning, and taken part in the Battles of Valmy and Jemappes. However, disillusioned with the leadership, he deserted to the Austrians in April 1793 and then spent many years in exile, mostly in the United States and England. He returned to France after the restoration of Louis XVIII in July 1815 and, with the forced abdication of Charles X in 1830, was seen as meeting the needs of a constitutional monarch. This “citizen king”, as he was dubbed, did usher in an administration dominated by the bourgeoisie rather than the aristocracy, but his reign - sometimes known as the July Monarchy - did not fulfil its early promise. At first, he played along with parliamentary government, attempting to please both the liberals and the monarchists, but by political intrigue and royal patronage his rule became increasingly authoritarian, and he proved unable to adapt to the social, commercial and industrial changes of his time. As we shall see, the last years of his reign were marred by corruption and economic depression, and he was overthrown in 1848 (Va), in Europe’s so-called Year of Revolutions.

xxxxxOn August 9th Louis Philippe (1773-1850), head of the house of Bourbon-Orleans, a branch of the French royal family, was proclaimed “king of the French by the grace of God and the will of the nation”. An arch liberal by royal standards, he had supported the French Revolution at its beginning, and taken part in the Battles of Valmy and Jemappes. However, disillusioned with the leadership, he deserted to the Austrians in April 1793 and then spent many years in exile, mostly in the United States and England. He returned to France after the restoration of Louis XVIII in July 1815 and, with the forced abdication of Charles X in 1830, was seen as meeting the needs of a constitutional monarch. This “citizen king”, as he was dubbed, did usher in an administration dominated by the bourgeoisie rather than the aristocracy, but his reign - sometimes known as the July Monarchy - did not fulfil its early promise. At first, he played along with parliamentary government, attempting to please both the liberals and the monarchists, but by political intrigue and royal patronage his rule became increasingly authoritarian, and he proved unable to adapt to the social, commercial and industrial changes of his time. As we shall see, the last years of his reign were marred by corruption and economic depression, and he was overthrown in 1848 (Va), in Europe’s so-called Year of Revolutions.

xxxxxNot surprisingly, the French revolution of July 1830 sparked off popular uprisings across Europe, particularly in Germany, Italy, Belgium and Poland. As we shall see (1831), some were ruthlessly crushed, as in the case of Germany and Poland, whilst others brought about political change of a l asting nature.

asting nature.

xxxxxIncidentally, in his novel Les Misérables, published in 1862, the French novelist Victor Hugo had this to say about Louis XVIII and Charles X: They believed they were rooted because they were the past. They were mistaken; they were a portion of the past, but the whole past was France. ……

xxxxx…… When Charles X was forced to abdicate he made for England and landed at Weymouth on the south coast. There he was met by a somewhat hostile crowd, and he quickly travelled inland and took refuge with the Welds, a Catholic family living in Lulworth Castle in Dorset. ……

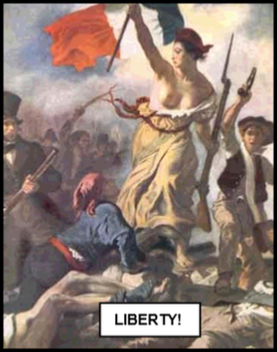

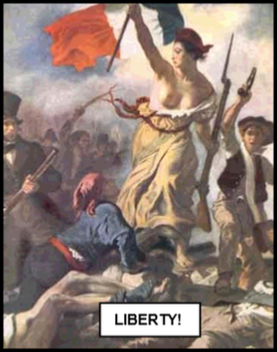

xxxxx…… In the July Revolution the white flag of the Bourbons was replaced by the tricolour, the flag adopted at the start of the French Revolution in 1789. The painting above (top right) - Liberty leading the people - in which the tricolour is given much prominence, was by the French artist Eugène Delacroix. As noted earlier, this patriotic work proved very popular and helped him to regain favour with the artistic establishment.

xxxxx…… In the July Revolution the white flag of the Bourbons was replaced by the tricolour, the flag adopted at the start of the French Revolution in 1789. The painting above (top right) - Liberty leading the people - in which the tricolour is given much prominence, was by the French artist Eugène Delacroix. As noted earlier, this patriotic work proved very popular and helped him to regain favour with the artistic establishment.

e eventually regained his throne following the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, he faced a daunting task. If his dynasty were to survive he had to find some way of satisfying the demands of the ultra-

e eventually regained his throne following the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, he faced a daunting task. If his dynasty were to survive he had to find some way of satisfying the demands of the ultra- xxxxxWith the death of Louis in September 1824, his younger brother, the Comte d'Artois, an ultra royalist, came to the throne as Charles X (illustrated) and confrontation became inevitable. A staunch supporter of the aristocracy and clergy, he compensated the emigrés for their loss of land during the Revolution, worked to revive the Church, and sanctioned the return of the Jesuits. At the same time, he at once set about undermining the liberal institutions and the popular rights which had been achieved by the Revolution and shrewdly tolerated by Louis. In particular, he saw freedom of the press, and the liberal opposition in the Chamber of Deputies, as a direct threat to society in general and to his dynasty in particular. He is recorded as saying that he would “rather chop wood than reign after the fashion of the King of England”!

xxxxxWith the death of Louis in September 1824, his younger brother, the Comte d'Artois, an ultra royalist, came to the throne as Charles X (illustrated) and confrontation became inevitable. A staunch supporter of the aristocracy and clergy, he compensated the emigrés for their loss of land during the Revolution, worked to revive the Church, and sanctioned the return of the Jesuits. At the same time, he at once set about undermining the liberal institutions and the popular rights which had been achieved by the Revolution and shrewdly tolerated by Louis. In particular, he saw freedom of the press, and the liberal opposition in the Chamber of Deputies, as a direct threat to society in general and to his dynasty in particular. He is recorded as saying that he would “rather chop wood than reign after the fashion of the King of England”! xxxxxThe events which brought matters to a head came about in 1830. In March, when the Chamber of Deputies demanded the dismissal of a number of the king’s ministers, Charles dissolved the legislature, declared the new elections null and void, and followed this up in July with a complete suspension of the freedom of the press. Such repressive measures aroused widespread opposition and violent resistance in Paris. Barricades were erected in the main thoroughfares, manned by students, workers and the petty bourgeoisie, and after three days of strikes and street fighting -

xxxxxThe events which brought matters to a head came about in 1830. In March, when the Chamber of Deputies demanded the dismissal of a number of the king’s ministers, Charles dissolved the legislature, declared the new elections null and void, and followed this up in July with a complete suspension of the freedom of the press. Such repressive measures aroused widespread opposition and violent resistance in Paris. Barricades were erected in the main thoroughfares, manned by students, workers and the petty bourgeoisie, and after three days of strikes and street fighting - xxxxxOn August 9th Louis Philippe (1773-

xxxxxOn August 9th Louis Philippe (1773- asting nature.

asting nature. xxxxx…… In the July Revolution the white flag of the Bourbons was replaced by the tricolour, the flag adopted at the start of the French Revolution in 1789. The painting above (top right) -

xxxxx…… In the July Revolution the white flag of the Bourbons was replaced by the tricolour, the flag adopted at the start of the French Revolution in 1789. The painting above (top right) -