xxxxxIn Britain, the years

following the Napoleonic Wars were deeply troubled by social and

political unrest, a situation made the more dangerous in 1830 with

the revolution in France and the overthrow of Charles X. In 1831 the

Whigs put forward a reform bill to increase the franchise and

provide a more equitable distribution of parliamentary seats. After

a struggle it was passed by the Commons, but then rejected by the

House of Lords. This caused violent disturbances in many parts of

the country, and held out the possibility of an all-out

revolution. Fearing such an outcome, William IV agreed to elect a

number of peers to outvote the Tory opposition. Faced with this

threat, the Tories capitulated and the Reform Bill of 1832 became an Act. By it,

members of the upper middle-class gained the right to vote, and

the seats in the Commons were more fairly distributed. It proved the

first step in the right direction, and further reform acts followed

in 1867 and 1884. Two social reforms were also made in the early

1830s. The Factory Act of 1833 limited the hours a child could work,

and the Poor Law of 1834 introduced the idea of the workhouse, a

means by which the destitute could be given food and shelter while

working for their keep.

THE FIRST REFORM ACT 1832 (W4)

Acknowledgements

Election: by

the English painter and social critic William Hogarth (1697-1764,

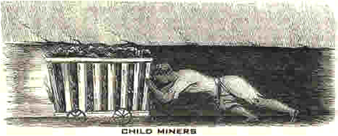

1755 – Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Miners:

from the first report of the Children’s Employment Commission,

Mines, 1842, artist unknown. Shaftesbury:

by the English painter George Frederick Watts (1817-1904) –

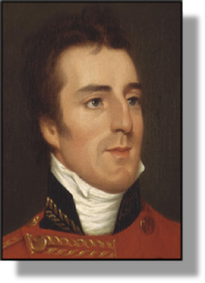

National Portrait Gallery, London. Wellington:

by the English portrait painter Robert Home (1752-1834), 1804

– National Portrait Gallery, London. Walmer Castle:

from England’s Topographer or A new and

Complete History of the County of Kent by

the English writer William Henry Ireland (1777-1835), 1828,

artist unknown. Duel: by the cartoonist

Thomas Howell Jones, 1829 – King’s College, London.

xxxxxBritain

emerged victorious from the Napoleonic Wars,

but the years after this military triumph were deeply troubled by

social and political unrest. There was widespread unemployment,

extreme hardship and exploitation within the ever-growing

factory system, and a smouldering resentment at the lack of

representation - be it by the middle classes at the outdated

political set-up, or by the working classes at the conditions

being endured in the work place. Some aspects of this discontent had

been shown earlier in the so-called Peterloo Massacre of 1819.

Liberalism had then been silenced, but by the early 1830s, popular

uprisings on the continent, notably in Poland, Germany and France

(where Charles X was overthrown), rekindled the demand for both

political and social reform.

xxxxxSuch was the clamour nation-wide that, in the House

of Commons the Tories, led by the hard-liner the Duke of

Wellington, were forced to make way for a Whig ministry committed to

parliamentary reform. It was long overdue. The distribution of

parliamentary constituencies had not been changed for decades. Rural

areas - much depopulated over the years - had the bulk of

parliamentary seats, whilst the new industrial towns like

Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds - teeming with people -

had none at all. Furthermore the abuses of a political system which

was firmly in the hands of the landed gentry, continued unabated.

There were over fifty “pocket” or “rotten” boroughs which could be

readily obtained at a price, or simply passed on to a relative or

friend. The borough of Old Sarum, for example, which sent two

representatives to the Commons, was a wasteland, the former site of

the city of Salisbury in Wiltshire. Nor were elections run on the

fairest of lines. There was plenty of bribery, corruption and

mayhem, as captured in William Hogarth’s “Election” series of the

1750s. (“Chairing the Member” illustrated

above).

xxxxxSuch was the clamour nation-wide that, in the House

of Commons the Tories, led by the hard-liner the Duke of

Wellington, were forced to make way for a Whig ministry committed to

parliamentary reform. It was long overdue. The distribution of

parliamentary constituencies had not been changed for decades. Rural

areas - much depopulated over the years - had the bulk of

parliamentary seats, whilst the new industrial towns like

Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds - teeming with people -

had none at all. Furthermore the abuses of a political system which

was firmly in the hands of the landed gentry, continued unabated.

There were over fifty “pocket” or “rotten” boroughs which could be

readily obtained at a price, or simply passed on to a relative or

friend. The borough of Old Sarum, for example, which sent two

representatives to the Commons, was a wasteland, the former site of

the city of Salisbury in Wiltshire. Nor were elections run on the

fairest of lines. There was plenty of bribery, corruption and

mayhem, as captured in William Hogarth’s “Election” series of the

1750s. (“Chairing the Member” illustrated

above).

xxxxxThe first reform bill was introduced in 1831. It was

strenuously opposed by the Tories, and it took the dissolving of

Parliament and an election of a new one before a majority could be

secured. This achieved, the bill was then rejected by the House of

Lords. This was the signal for disturbances across the country.

There were fierce riots in London, Birmingham, Nottingham, Derby and

Bristol, and the military had to be called in to stop the sacking

and burning of buildings. The king, fearing a nation-wide

rebellion, reluctantly agreed to create new peers to out-vote

the Tory majority. However, such a move proved unnecessary, and the

possibility of a July Revolution (as in France two years earlier)

was averted. When the bill came before the Lords a second time in

the spring of 1832 about one hundred

peers stayed away - led by the Duke of Wellington - and

the bill became an Act.

xxxxxThe first reform bill was introduced in 1831. It was

strenuously opposed by the Tories, and it took the dissolving of

Parliament and an election of a new one before a majority could be

secured. This achieved, the bill was then rejected by the House of

Lords. This was the signal for disturbances across the country.

There were fierce riots in London, Birmingham, Nottingham, Derby and

Bristol, and the military had to be called in to stop the sacking

and burning of buildings. The king, fearing a nation-wide

rebellion, reluctantly agreed to create new peers to out-vote

the Tory majority. However, such a move proved unnecessary, and the

possibility of a July Revolution (as in France two years earlier)

was averted. When the bill came before the Lords a second time in

the spring of 1832 about one hundred

peers stayed away - led by the Duke of Wellington - and

the bill became an Act.

xxxxxThe

reform measures which were introduced were nothing short of

“sweeping” in the context of the time. The pocket and rotten

boroughs were abolished, parliamentary seats were redistributed on a

much more representative basis, and the franchise was extended,

based on quite a liberal property qualification. As a result the

upper-middle classes gained the vote for the first time, and

the total number of voters was increased from around 440,000 to

657,000. Vast sections of the population, of course, remained

without a vote, and landed interest remained dominant in the new

House of Commons, but it was a start. As we shall see, a further

extension of the franchise, the Second Reform Act, was made in 1867

(Vb) - due

in large measure to the Chartist Movement - and then in 1884

(Vc) voting rights were again extended (the Third Reform Act),

together with another redistribution of parliamentary seats. By

then, aristocratic privilege had come to an end.

xxxxxOtherxreforms followed in an

attempt to tackle some of the worst social evils of the day. The Factory Act of 1833 was

directed at the appalling abuse of child labour. In many factories

children of seven were put to work for twelve or more hours a day.

The law prohibited the employment of children under the age of nine

and, until they reached thirteen, limited their working week to 48

hours. Some schooling was also provided during the day, the first

step on the long road to compulsory, universal education. Thexfollowing year changes were also made in the poor laws.

The Poor Law of 1834

saw the introduction of the workhouse, an institution which, despite

all its faults, attempted to give the unemployed food and shelter

whilst working for their keep.

xxxxxOtherxreforms followed in an

attempt to tackle some of the worst social evils of the day. The Factory Act of 1833 was

directed at the appalling abuse of child labour. In many factories

children of seven were put to work for twelve or more hours a day.

The law prohibited the employment of children under the age of nine

and, until they reached thirteen, limited their working week to 48

hours. Some schooling was also provided during the day, the first

step on the long road to compulsory, universal education. Thexfollowing year changes were also made in the poor laws.

The Poor Law of 1834

saw the introduction of the workhouse, an institution which, despite

all its faults, attempted to give the unemployed food and shelter

whilst working for their keep.

xxxxxIncidentally, it was at this time (as noted earlier) that the

politician Sir Robert Peel, in order to shed the Tories of their

reactionary image and thus widen their membership, defined the aims

of the party in his Tamworth Address of 1834. This advocated measures of reform within

existing institutions, stressed the importance of law and order, and

promised continued support to trade, industry and the landed

interests. This address is often seen as the launch of the modern

Conservative Party, a term first used by the writer and arch Tory

John Wilson Croker in the Quarterly Review

of January 1830. The Whigs adopted the title of the Liberal Party in

the late 1830s, though the first Liberal government in the modern

sense was not formed until 1868. ……

xxxxx…… Axstout

supporter of the Reform Bill was the Whig politician Henry

(later Baron) Brougham (1778-1868), a

man of fashion who was known for his wit and somewhat eccentric

behaviour. He helped to found the Edinburgh

Review in 1802, played a leading part in the foundation of

London University, and was Lord Chancellor form 1830-34. He

supported a number of other good causes, including education and law

reform, but he is best remembered today for his design of “The

Brougham”, originally a four-wheeled carriage drawn by one

horse. He spent most of his last thirty years in Cannes, on the

French Riviera, and it was there that he died in 1868.

xxxxx…… Axstout

supporter of the Reform Bill was the Whig politician Henry

(later Baron) Brougham (1778-1868), a

man of fashion who was known for his wit and somewhat eccentric

behaviour. He helped to found the Edinburgh

Review in 1802, played a leading part in the foundation of

London University, and was Lord Chancellor form 1830-34. He

supported a number of other good causes, including education and law

reform, but he is best remembered today for his design of “The

Brougham”, originally a four-wheeled carriage drawn by one

horse. He spent most of his last thirty years in Cannes, on the

French Riviera, and it was there that he died in 1868.

xxxxxAnother Englishman of this

period who played a prominent part in supporting and guiding major

social reforms through parliament was the statesman and

philanthropist Anthony Ashey Cooper, the 7th Earl

of Shaftesbury (1801-1885). He served

in the House of Commons for twenty five years before he succeeded to

the earldom and took his seat in the Lords. Ironically enough, he

was not in favour of the Reform Bill, being against the widening of

the franchise, but he did much to improve working conditions in

factories, especially for women and children, and as a member of the

Ragged School Union he was instrumental in providing free education

for the poor. He also supported the Mines Act of 1842, which put an

end to women and children working underground, and the Lunacy Act of

1845, aimed at improving asylums for “persons of unsound mind”.

xxxxxAnother Englishman of this

period who played a prominent part in supporting and guiding major

social reforms through parliament was the statesman and

philanthropist Anthony Ashey Cooper, the 7th Earl

of Shaftesbury (1801-1885). He served

in the House of Commons for twenty five years before he succeeded to

the earldom and took his seat in the Lords. Ironically enough, he

was not in favour of the Reform Bill, being against the widening of

the franchise, but he did much to improve working conditions in

factories, especially for women and children, and as a member of the

Ragged School Union he was instrumental in providing free education

for the poor. He also supported the Mines Act of 1842, which put an

end to women and children working underground, and the Lunacy Act of

1845, aimed at improving asylums for “persons of unsound mind”.

xxxxxToday, Shaftesbury is

especially remembered for persuading Parliament in 1846 to forbid

the use of young children being used as chimney sweeps. Among those

he assisted financially were Florence Nightingale in her work to

improve hospital nursing, and Thomas Barnardo in his provision of

homes for destitute children. He was leader of the evangelical

movement within the Church of England and favoured the political  emancipation

of Roman Catholics.

emancipation

of Roman Catholics.

xxxxxIncidentally, in 1893 a memorial was erected in Piccadilly Circus,

London, to commemorate Lord

Shaftesbury’s work for good causes. It was crowned by a nude figure

of Anteros, a butterfly-winged

archer depicting the Greek God of unrequited love. However, the

figure was mistaken for Eros, the God of

love, and the monument became known by that name! Today it is a

London landmark. ……

xxxxx……

Thexwork of the Ragged School Union, which

Shaftsbury helped to found in 1844, was actually started some forty

years earlier by John Pounds (1766-1839). Born in Portsmouth, he became a

shipwright apprentice at the age of 12, but three years later he was

badly injured at work and became a cripple for life. He took up shoe

making and around 1802, while working at his shop in Portsmouth, he

began to give free schooling to local poor children. The idea was

taken up by others and the scheme eventually came to the notice of

Shaftsbury. He put it on a firm footing.

Including:

The Earl of Shaftesbury

and The Duke of

Wellington

W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4-1830-1837-W4

xxxxxIn contrast to Lord

Shaftsbury, a politician who lost a great deal of public support

because of his opposition to political and social reform was the Duke of Wellington. As we have

seen, on becoming Tory prime minister in 1828 he had antagonised his

party by making a U-turn and pushing through the Catholic

Emancipation Act of 1829, a decision he thought necessary to avoid a

civil war in Ireland. The following year, however, he lost the

support of the majority of the country’s population by coming out

strongly against any reform measures. This uncompromising stand

brought about the downfall of his government and made him a target

of abuse. As we have seen (1815 G3c), on returning to England after the Battle of Waterloo

Wellington was drawn into politics. He served as a Tory until

resigning in 1827, and the following year was made prime minister at

the insistence of William IV. It was then that he ran into trouble

with his own party over the question of Catholic Emancipation, and

then angered the public by his anti-reform policy. Later, in

the early 1840s, he assisted Sir John Peel in abolishing the Corn

Laws - against his own judgement once again - but retired

from public life in 1846. He held many public offices during his

long career, and was advisor to the young Queen Victoria. As a

soldier, he lacked the common touch, but he was an outstanding

commander, albeit somewhat cautious at times. As a politician he was

reactionary by nature, but it is to his credit that he was prepared,

when necessary, to put aside his own views in the interest of his

nation’s welfare. Few men have served their country better.

xxxxxBy contrast, one politician at this time who lost a

great deal of public support because of his fervent opposition to

any political or social reform was the Duke

of Wellington. As we have seen, as Tory

prime minister he had angered many of his party in 1829 by doing a

U-turn and pushing through the Catholic Emancipation Act

(giving civil and political rights to Roman Catholics). He had then

gone along with his home secretary, Sir John Peel, to avoid a

possible civil war in Ireland, but his action was seen by hard-liners

as a betrayal of Tory principles. In 1830, however, he pleased his

party but alienated the general public by speaking out against any

reform measures whatsoever. He argued, in particular, that there was

nothing wrong with the present electoral system, and any changes to

it would ruin the country. This uncompromising stand not only

brought about the prompt downfall of his weak and unpopular

government, but also made him a target for abuse. The windows of

Apsley House, his residence near Hyde Park Corner, were smashed by

violent mobs on more than one occasion, and he was obliged to put up

iron shutters to stop further damage. It was that action, not his

glorious career on the battlefield, which earned him the title of

“the Iron Duke”!

xxxxxBy contrast, one politician at this time who lost a

great deal of public support because of his fervent opposition to

any political or social reform was the Duke

of Wellington. As we have seen, as Tory

prime minister he had angered many of his party in 1829 by doing a

U-turn and pushing through the Catholic Emancipation Act

(giving civil and political rights to Roman Catholics). He had then

gone along with his home secretary, Sir John Peel, to avoid a

possible civil war in Ireland, but his action was seen by hard-liners

as a betrayal of Tory principles. In 1830, however, he pleased his

party but alienated the general public by speaking out against any

reform measures whatsoever. He argued, in particular, that there was

nothing wrong with the present electoral system, and any changes to

it would ruin the country. This uncompromising stand not only

brought about the prompt downfall of his weak and unpopular

government, but also made him a target for abuse. The windows of

Apsley House, his residence near Hyde Park Corner, were smashed by

violent mobs on more than one occasion, and he was obliged to put up

iron shutters to stop further damage. It was that action, not his

glorious career on the battlefield, which earned him the title of

“the Iron Duke”!

xxxxxAs we have seen (1815 G3c), after his career

in the army, Wellington returned to England in 1818 and was drawn

into the political arena. A straightforward and honest man, he was

not always at home in this new “battlefield”. He served in the Tory

government of Lord Liverpool, attending the Congress of Verona in

1822, but resigned in 1827 (taking half the cabinet with him!) when

George Canning - who favoured Catholic Emancipation -

became prime minister. The following year, however, on the

insistence of William IV, he formed his own government, and it was

then, over the next two years, that he became unpopular with his

party, first over his support of Catholic Emancipation, and then

with the population at large over his reactionary stand against any

measure of reform, political or social.

xxxxxDuring the mid-1830s

he served as foreign secretary under Peel and then, as minister

without portfolio, assisted him in abolishing the Corn Laws, acting

against his own judgement once again. He retired from public life in

1846. Among the offices he held during his political career were

commander in chief of the forces - an appointment made

permanent in 1842 -, chancellor of the University of Oxford,

constable of the Tower, and master of Trinity House. He was an

advisor and father figure to the young Queen Victoria, and, as Lord

Warden of the Cinque Ports, he was living at Walmer Castle in Kent (illustrated) when he died of a

stroke in 1852. He was given a monumental state funeral - one

befitting the “Great Duke” - and was buried in St. Paul’s

Cathedral.

xxxxxAs a soldier, Wellington

was an outstanding general, though he lacked the common touch and is

viewed by some as a rather over-cautious commander. As a

politician he was certainly reactionary, but, when necessary, he was

prepared to compromise his own views in the interests of his

country, and he was honest and upright in all his dealings. He was,

indeed, a public servant without rival during a long and

distinguished career.

xxxxxIncidentally, having

eventually persuaded his party and the king to accept Catholic

Emancipation in 1829 - his greatest political triumph -

Wellington was criticised by a number of die-hard Tories. By

all accounts, one of them, the Earl of Winchelsea, went so far as to

insult the Duke and was challenged to a duel. The contest took place

at Battersea Fields but, having made their point, both men chose to

shoot wide deliberately! ……

xxxxxIncidentally, having

eventually persuaded his party and the king to accept Catholic

Emancipation in 1829 - his greatest political triumph -

Wellington was criticised by a number of die-hard Tories. By

all accounts, one of them, the Earl of Winchelsea, went so far as to

insult the Duke and was challenged to a duel. The contest took place

at Battersea Fields but, having made their point, both men chose to

shoot wide deliberately! ……

xxxxx……

In 1817 a grateful nation presented Wellington with the stately home

and estate of Stratfield Saye in the county of Hampshire, and it has

remained the home of the Dukes of Wellington ever since. The Duke’s

London home was Apsley House at Hyde Park Corner, and this now

serves as a museum and an art gallery, run by English Heritage.

xxxxxSuch was the clamour nation-

xxxxxSuch was the clamour nation- xxxxxThe first reform bill was introduced in 1831. It was

strenuously opposed by the Tories, and it took the dissolving of

Parliament and an election of a new one before a majority could be

secured. This achieved, the bill was then rejected by the House of

Lords. This was the signal for disturbances across the country.

There were fierce riots in London, Birmingham, Nottingham, Derby and

Bristol, and the military had to be called in to stop the sacking

and burning of buildings. The king, fearing a nation-

xxxxxThe first reform bill was introduced in 1831. It was

strenuously opposed by the Tories, and it took the dissolving of

Parliament and an election of a new one before a majority could be

secured. This achieved, the bill was then rejected by the House of

Lords. This was the signal for disturbances across the country.

There were fierce riots in London, Birmingham, Nottingham, Derby and

Bristol, and the military had to be called in to stop the sacking

and burning of buildings. The king, fearing a nation- xxxxxOtherxreforms followed in an

attempt to tackle some of the worst social evils of the day. The Factory Act of 1833 was

directed at the appalling abuse of child labour. In many factories

children of seven were put to work for twelve or more hours a day.

The law prohibited the employment of children under the age of nine

and, until they reached thirteen, limited their working week to 48

hours. Some schooling was also provided during the day, the first

step on the long road to compulsory, universal education. Thexfollowing year changes were also made in the poor laws.

The Poor Law of 1834

saw the introduction of the workhouse, an institution which, despite

all its faults, attempted to give the unemployed food and shelter

whilst working for their keep.

xxxxxOtherxreforms followed in an

attempt to tackle some of the worst social evils of the day. The Factory Act of 1833 was

directed at the appalling abuse of child labour. In many factories

children of seven were put to work for twelve or more hours a day.

The law prohibited the employment of children under the age of nine

and, until they reached thirteen, limited their working week to 48

hours. Some schooling was also provided during the day, the first

step on the long road to compulsory, universal education. Thexfollowing year changes were also made in the poor laws.

The Poor Law of 1834

saw the introduction of the workhouse, an institution which, despite

all its faults, attempted to give the unemployed food and shelter

whilst working for their keep.  xxxxx…… Axstout

supporter of the Reform Bill was the Whig politician Henry

(later Baron) Brougham (1778-

xxxxx…… Axstout

supporter of the Reform Bill was the Whig politician Henry

(later Baron) Brougham (1778- xxxxxAnother Englishman of this

period who played a prominent part in supporting and guiding major

social reforms through parliament was the statesman and

philanthropist Anthony Ashey Cooper, the 7th Earl

of Shaftesbury (1801-

xxxxxAnother Englishman of this

period who played a prominent part in supporting and guiding major

social reforms through parliament was the statesman and

philanthropist Anthony Ashey Cooper, the 7th Earl

of Shaftesbury (1801-

emancipation

of Roman Catholics.

emancipation

of Roman Catholics.

xxxxxBy contrast, one politician at this time who lost a

great deal of public support because of his fervent opposition to

any political or social reform was the Duke

of Wellington. As we have seen, as Tory

prime minister he had angered many of his party in 1829 by doing a

U-

xxxxxBy contrast, one politician at this time who lost a

great deal of public support because of his fervent opposition to

any political or social reform was the Duke

of Wellington. As we have seen, as Tory

prime minister he had angered many of his party in 1829 by doing a

U-

xxxxxIncidentally, having

eventually persuaded his party and the king to accept Catholic

Emancipation in 1829 -

xxxxxIncidentally, having

eventually persuaded his party and the king to accept Catholic

Emancipation in 1829 -