xxxxxIt was in the spring of 1706 that the French located an Anglo-Dutch force near the village of Ramillies, about 12 miles north of Namur in today’s Belgium. The French commander, the Duke de Villeroi, deployed his troops along a four mile ridge and this proved his undoing. The Allies, led by the Duke of Marlborough, launched unsuccessful attacks on the left and centre of the French line, but when the Dutch advanced on the enemy’s right flank, Villeroi, over-extended, moved men from the centre to counter this threat. Using his English infantry, Marlborough then struck hard through the weakened centre and, joining up with the Dutch, caught the enemy in a vice. The French fled the field, losing all their artillery, and suffering some 6,000 casualties. By this victory large areas of the Spanish Netherlands were recaptured.

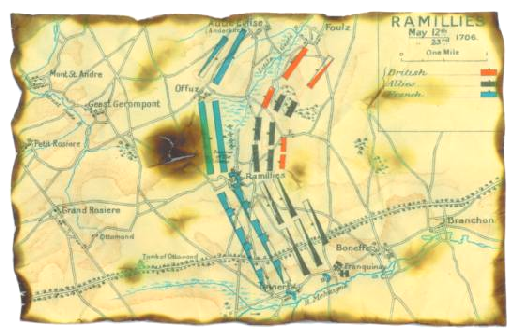

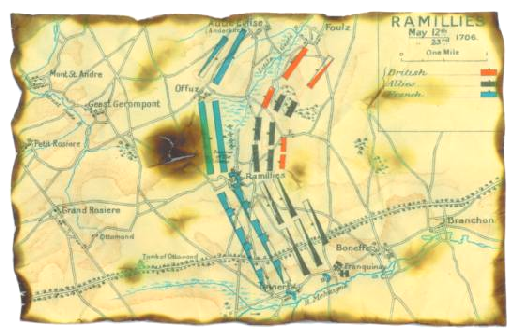

xxxxxItxwas in the spring of 1706 when, under express orders from Louis XIV, the French commander, François de Neufville, Duke de Villeroi (1644-1730), went in search of a fight. Having located the Anglo-Dutch force under the command of the Duke of Marlborough, he chose the plain of Ramillies for the battle and deployed his troops along a four mile ridge. He placed his cavalry on the wings and his infantry in the centre, close to the villages of Ramillies and Offus.

xxxxxThe two sides were evenly matched in numbers - around 60,000 men each - but the French were overextended on a long front and this contributed to their defeat. The English and Dutch opened the battle by attacking the French left flank, but marshland slowed down the advance and little was achieved. Then an attack by Dutch cavalry in the centre of the line fared no better. They were repulsed and suffered heavy casualties. The break-through came when Marlborough used his Dutch infantry to attack a small village on the French right flank. Villeroi moved troops from the centre to counter this threat and - as in the Battle of Blenheim - Marlborough then launched an attack on the depleted area. The English infantry, reinforced by troops moved from the right wing, struck hard through the French centre and overran Ramillies. At the same time the Dutch, breaking through on the French right, moved behind the enemy lines, driving the French towards the advancing English. Caught in a vice, they broke up in disarray and fled the field. The French lost all their artillery, and suffered some 16,000 casualties, whereas the allied losses were fewer than 5,000 killed and wounded.

xxxxxThe two sides were evenly matched in numbers - around 60,000 men each - but the French were overextended on a long front and this contributed to their defeat. The English and Dutch opened the battle by attacking the French left flank, but marshland slowed down the advance and little was achieved. Then an attack by Dutch cavalry in the centre of the line fared no better. They were repulsed and suffered heavy casualties. The break-through came when Marlborough used his Dutch infantry to attack a small village on the French right flank. Villeroi moved troops from the centre to counter this threat and - as in the Battle of Blenheim - Marlborough then launched an attack on the depleted area. The English infantry, reinforced by troops moved from the right wing, struck hard through the French centre and overran Ramillies. At the same time the Dutch, breaking through on the French right, moved behind the enemy lines, driving the French towards the advancing English. Caught in a vice, they broke up in disarray and fled the field. The French lost all their artillery, and suffered some 16,000 casualties, whereas the allied losses were fewer than 5,000 killed and wounded.

xxxxxThe victory at Ramillies, fought 12 miles north of Namur in present-day Belgium, enabled the allies to recapture large areas of the Spanish Netherlands, mostly in the north and east. As we shall see, the victory at the Battle of Oudenaarde, two years later (1708) helped to free most other parts of the country.

THE BATTLE OF RAMILLIES 1706 (AN)

THE WAR OF THE SPANISH SUCCESSION

xxxxxIn the same year as the Battle of Ramillies, the Austrian general Prince Eugene of Savoy (1663-1736) raised the siege of Turin and drove the French out of Italy, a major achievement. He was a Frenchman by birth, but joined the Austrian army in 1683. He soon distinguished himself against the French and the Ottoman Turks, defeating the latter at the Battle of Zenta in 1697, and forcing them to make sweeping concessions. In the War of the Spanish Succession he shared with Marlborough the victory at Blenheim and, later, played a vital role in the defeat of the French at Oudenaarde and Malplaquet. When the war was over he again took on the Ottomans, forcing them to accept the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718 (G1), and he led the imperial army in the War of the Polish Succession. A commander of exceptional daring and valour, Napoleon regarded him as one of the greatest strategists of all time.

Including:

Prince Eugene

of Savoy

xxxxxInxthe same year as the Battle of Ramillies, the Austrian general Prince Eugene of Savoy - the commander who had shared with Marlborough the great victory at Blenheim - raised the siege of Turin and finally drove the French out of Italy. Up until this time the French had dominated this theatre of the war, and there had seemed little likelihood of defeating them. For this outstanding achievement he was promoted lieutenant general and made governor of Milan.

xxxxxInxthe same year as the Battle of Ramillies, the Austrian general Prince Eugene of Savoy - the commander who had shared with Marlborough the great victory at Blenheim - raised the siege of Turin and finally drove the French out of Italy. Up until this time the French had dominated this theatre of the war, and there had seemed little likelihood of defeating them. For this outstanding achievement he was promoted lieutenant general and made governor of Milan.

xxxxxIronically enough, Eugene was himself a Frenchman by birth. He was born in Paris in 1663, but, after a number of unsuccessful attempts to obtain a commission in Louis XIV's army, he renounced his French citizenship and in 1683 joined the Austrian army, then under the command of the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I. His decision proved to be a real gain for Austria and a great loss for France. He soon distinguished himself on the battlefield, first against his former sovereign in the War of the Grand Alliance, and then against the Ottomans. It was he who, in 1697, at the age of 34, was appointed commander of the imperial army in Hungary and routed the Turks at the famous Battle of Zenta, forcing them to make sweeping concessions at the Peace of Karlowitz two years later. We are told that Louis XIV was so impressed with his courage and leadership ability that he offered to make him a marshal of France and ruler of the province of Champagne, but Eugene declined the offer.

xxxxxOn the outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession, he served for a short while in Italy and then returned to Vienna in 1702 to become president of the Imperial Council of War. It was in this capacity that he shared with Marlborough in the great victory at Blenheim, and then went on to defeat the French at Turin. Later, as we shall see, he again allied with his friend Marlborough and shared in the victories at Oudenaarde and Malplaquet. Onlyxin 1712, towards the end of the war, was he defeated at Denain by the French, and forced to come to terms at the Treaties of Rastatt and Baden.

xxxxxThe War of the Spanish Succession once over, he received command of the Hungarian army and was soon fighting the Ottoman Turks again. As we shall see, he won a series of battles and brought the war to a satisfactory conclusion with the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718 (G1). Six years later he became vicar-general of Italy and held this post until given command of the imperial army in the War of the Polish Succession. He died in 1736, soon after the war's conclusion, but his reputation lived on. A leader of remarkable daring and valour (he was wounded thirteen times), he often used unorthodox tactics, but planned his campaigns with meticulous care. Napoleon regarded him as one of the greatest strategists of all time.

xxxxxThe War of the Spanish Succession once over, he received command of the Hungarian army and was soon fighting the Ottoman Turks again. As we shall see, he won a series of battles and brought the war to a satisfactory conclusion with the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718 (G1). Six years later he became vicar-general of Italy and held this post until given command of the imperial army in the War of the Polish Succession. He died in 1736, soon after the war's conclusion, but his reputation lived on. A leader of remarkable daring and valour (he was wounded thirteen times), he often used unorthodox tactics, but planned his campaigns with meticulous care. Napoleon regarded him as one of the greatest strategists of all time.

xxxxxIncidentally, it was rumoured at one time that Eugene was an illegitimate son of Louis XIV, and that his mother had been exiled on account of the affair. If this were so, it could well account for the offhand treatment he received at the French court, and the reason why he failed to obtain a commission in the army.

Acknowledgements

Battle Plan: location unknown. Prince Eugene: by the French/Austrian painter and engraver Jacob van Schuppen (1670-1751), 1718 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

AN-1702-1714-AN-1702-1714-AN-1702-1714-AN-1702-1714-AN-1702-1714-AN-1702-1714-AN

xxxxxThe two sides were evenly matched in numbers -

xxxxxThe two sides were evenly matched in numbers -

xxxxxInxthe same year as the Battle of Ramillies, the Austrian general Prince Eugene of Savoy -

xxxxxInxthe same year as the Battle of Ramillies, the Austrian general Prince Eugene of Savoy - xxxxxThe War of the Spanish Succession once over, he received command of the Hungarian army and was soon fighting the Ottoman Turks again. As we shall see, he won a series of battles and brought the war to a satisfactory conclusion with the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718 (G1). Six years later he became vicar-

xxxxxThe War of the Spanish Succession once over, he received command of the Hungarian army and was soon fighting the Ottoman Turks again. As we shall see, he won a series of battles and brought the war to a satisfactory conclusion with the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718 (G1). Six years later he became vicar-